Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe heresy of King's Mountain

WALTER LIPPMANN

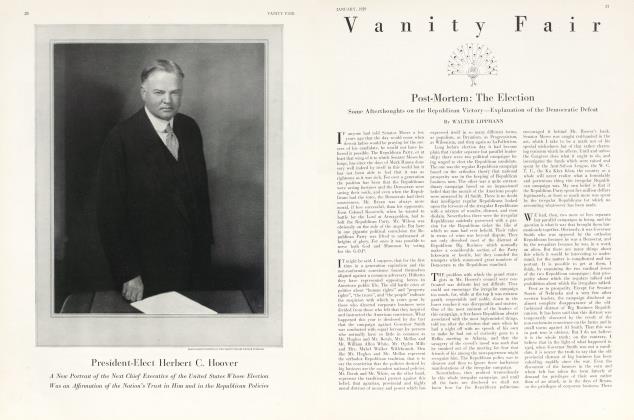

How Mr. Hoover follows a tradition in expounding a national creed equating great wealth with virtue

Though it is not one of his duties enumerated in the Constitution, custom now requires the President to find occasions for expounding American ideals. Standing in the line of Washington and Lincoln he must add his prophecy to the canon of great utterances like the Farewell Address and the Gettysburg speech, and so in the last seven or eight years Mr. Coolidge and Mr. Hoover have prophesied frequently on the subject of American ideals. Always they have insisted that they were repeating the orthodox faith. I think they are mistaken. It seems to me that unconsciously or otherwise they have fallen into deep, dangerous, and vulgar heresy. I refer to the doctrine that our superior riches are a measure and sign of our superior virtue, that we Americans are richer per capita because per capita we are nobler.

Just the other day on the battlefield of King's Mountain this doctrine was expounded once more by Mr. Hoover. He had come, he said, to this scene of inspiring memories not only to celebrate the valor of the revolutionists who fought there but to speak about the institutions, about the ideals, about the spirit of America. Our principles and ideals, he went on to explain, have never "been assembled elsewhere and combined into government". We have established a system of equal opportunity, of free and universal education, and of fair competition in which "the winner" of "the race" is "he who shows the most conscientious training, the greatest ability, the strongest character". The test of this system, lie then declared, "as compared to others" may "'in part be interpreted by the practical results". There are, it is true, "the great intangibles of the spirit" with which we are amply endowed, but "the test" of our principles and ideals may be made by comparing our material possessions with those of other nations. "I can give you," said the President of the United States, "some measurement both of our standards and of our social progress."

As compared with the most advanced country in Europe we have in proportion to our population one-fourth more of our children in grade schools, and we have six and a half times as many in colleges and universities; in fact we have more youths "in institutions of higher learning than all the rest of the billion and a half people of the world put together". We are not only the supremely well-educated people of the planet; we are "incomparably" richer than other people. Thus:

"We have twice the number of homes owned among every thousand people than they have."

"We have four times as much electricity."

"And we have seven times as many auto-mobiles."

"For each thousand people we have more than four times as many telephones and radio sets."

"Our use of food and clothing is far greater."

"We have proportionately only one-twentieth as many people in the poor house or upon public charity."

In such words the two last Presidents of the United States have seen fit to address their countrymen at home and their fellowmen abroad. Virtue, they say, is richly rewarded: the best ideals, the greatest ability, the strongest characters may be measured by the possessions accumulated. This, they say, is our national philosophy; we are willing to submit the validity of our institutions, our ideals, and our personal characters to the test of material success.

We can test this test, I think, by a simple device. Let us imagine a speech made not by the President of the United States but by the President of the Associated Income Taxpayers in the Higher Brackets. He has read Mr. Coolidge and Mr. Hoover diligently. He subscribes to their gospel. He proceeds to apply it to the members of his association, all of them officially and statistically established as winners of that race which Mr. Hoover says "is a system unique with America". He is speaking at a spot of inspiring memories, say from the rostrum of the Stock Exchange overlooking the scene where American Tel. and Tel. once sold for 310 1/4:—

"No American can review the vast pageant of human progress without renewed faith in humanity, new courage and strengthened resolution. My friends, I have lived among many classes of Americans. Many of them I have learned to respect and admire. It is from these contrasts and these experiences that I wish to speak to-day—to speak upon the ideals and the spirit of the American rich.

"My fellow surtax payers live in a stronger security and in greater comfort than have ever before been the fortune of other Americans. We are the winners in the race of life because we have shown the most conscientious training, the greatest ability, and the strongest characters. The test of our system of doing business, of our principles, and of our ideals as compared with those of the members of the middle class, the farmers, the clerks, and the workingmen may in part be interpreted by the practical results. I can give you some measurement both of our standards and of our social progress.

"In proportion to our numbers we have more children brought up by French governesses than the most advanced members of the middle class. We have more children in excellent private schools. We have six times as many of our young people in universities. We have, conservatively speaking, eight and three quarters times as many private tutors to get our young men through the college examinations. I may add that we have more of our youths in institutions of higher learning than all the coal-miners, stevedores, delicatessen store keepers and night watchmen put together.

"Each of us has more homes owned than the farmers have, for we have not only a home at Newport or Southampton, but also a home in the city, a home in Palm Beach, and the most winning of the winners among our winning set also have a shooting lodge in Scotland and a villa on the Riviera. We consume at least four times as much gasoline in our yachts as all the servant girls, and we have not only at least twice as many automobiles per capita as the plumbers, hut they are twice as fast, twice as shiny, and they have better balloon tires. We have four times as many telephones in our homes, eleven times as many polo ponies on our estates, and per capita we own more boxes at the opera. Our use of food, and may I add, champagne, of clothing, and, may I add. emeralds and ermine, is far greater. We have proportionately not one-twentieth as many of our relations in the poor house or upon public charity."

(Continued on page 108)

(Continued from page 52)

It is not likely, I suppose, that this speech which I have just sketched out will be delivered in any public place. It would not be safe to make such a speech, for I am afraid that Americans are not sufficiently loyal to the national philosophy which Mr. Hoover imputes to them, to bear patiently with such an application of the logic of this philosophy. It may be safe to throw such a philosophy in the face of Englishmen, Germans, Italians, and Czechs, it being impossible to throw a brick back across three thousand miles of ocean, hut it would not be prudent to say such things to Americans. Yet if Mr. Hoover's utterance is indeed the national philosophy, for which the men who died at Lexington, Bunker Hill, Trenton and Yorktown, Antietam. Gettysburg, Belleau Wood, and the Argonne were fighting, then he ought to be able to apply that philosophy not only externally but within our frontiers as well.

Happily for the internal peace of the Republic not even the newest of the newly rich would dare to offer himself publicly as an illustration of the Coolidge-TIoover doctrine. Thus our latest Presidential philosophy seems to be applicable to the American nation as a whole but not to Americans individually. We are asked to believe that it is patriotic to say of Americans collectively what it would be excruciatingly vulgar to say of them separately.

There are, to be sure, many things permitted to men collectively which are prohibited to them personally. They may kill collectively. They may trespass on their neighbor's lands. They may burn cities. They may starve babies. They may seize property. They may denounce contracts. They may hold themselves above any law of God or man. And so perhaps it is permitted them to say collectively that they are richer than their neighbor's friends because they are more virtuous.

We should, however, miss the peculiar essence of this new Presidential gospel if we saw in it only the latest manifestation of the tendency in all nations to proclaim themselves the chosen of God. There is a special quality in the current doctrine of national self-approval which is, 1 think, new. I do not know any precedents for it in the utterances of the pre-war Presidents. To be sure I have not read all their utterances, but where among the memorable addresses and state papers from Washington to Wilson can one find a national philosophy which equates affluence with virtue, and compares American good fortune, loudly and repeatedly with the fortunes of the rest of mankind?

Mr. Coolidge did not, of course, invent the doctrine. It could be shown to those who are curious in these matters that he came by it honestly, and that what we have in his view of life is a rare specimen, perfectly preserved, of the tradition which once flourished in certain sects of dissenters among the commercial classes of Seventeenth Century England. Just as one can still find traces of the Elizabethan speech in the mountains of Tennessee, so here from the granite hills of Vermont is the commercial morality of the rising business men of two and three generations before Queen Anne.

Thus, for example, in Richard Steele's, The Tradesman's Calling, published in 1684, the theory is advanced that success in business is a proof that a man has labored faithfully in his calling and that "God has blessed his trade". Historians like Sombart, Max Weber, Tawney and others showed that this new ethic played a great part in the development of modern business by helping to break down the deep distrust of the acquisitive motive which is characteristic of the main feeling of Christianity. This commercial ethic was transplanted to America, but until Calvin Coolidge it had never become identified with national patriotism.

The introduction into the national philosophy of this peculiar mixture of piety and acquisitiveness was due to a combination of coincidences. It happened that about 1924 the United States was on the upside of a business cycle, that the older nations were still weakened and distraught by the effects of the war, that the United States had unexpectedly become the strongest world power and had gone through a revulsion of feeling against responsibilities which it was unprepared to bear, when, by a series of political accidents, there was elevated to the Presidency a man who sincerely and naively believed that the boom in our trade was the consequence of our superiority in civilization. He preached the dogma of pious acquisitiveness; stocks went up, twice his party swept the country, and the dogma was carried to all corners of the land on the gasses of the great bull market.

Much was permitted to Mr. Coolidge that is not permitted to Mr. Hoover. He is mistaken if he thinks that the success of the Coolidge gospel was anything but a temporary aberration in an era when so many values, financial and moral, were false. Mr. Hoover is living in a time when the hard realities are evident, and it should be evident to him that a great people, composed as it must be of rich and poor, of winners and losers, and of many, very many, who are not "racing", but trying to live, can never be united by a creed which has as its central thesis the odious comparison between those who own much and those who own less. I do not dwell upon the imprudence of such a philosophy in a world torn by class and sectional and even continental jealousies. I would suggest simply that Mr. Hoover ask himself whether the instinct of American national leaders was not sound when they refrained from identifying the national destiny with national prosperity.

(Continued on page 126)

(Continued from page 108)

For has it never occurred to him that no one, not even the Republican Party, can guarantee that America will always be more prosperous than other lands, that America might lose the economic preeminence which it so recently acquired, for fortunate as she is, she is not immune from circumstances and the unending changes in human affairs? What, then, of patriotism, institutions, ideals, if the coming generation of Americans were to accept and believe the theory that the most prosperous state is the best one? It would be better to found American loyalty now, as in the past, upon the immeasurable and mystical affections that men have for the land to which they belong, and to let go altogether, to reject and extirpate the heresy that the possession of seven times as many automobiles as some other nation has anything whatsoever to do with American institutions and ideals. For there may come a time when some other people may have more worldly goods per capita than we have. It is conceivable.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now