Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDining for profit

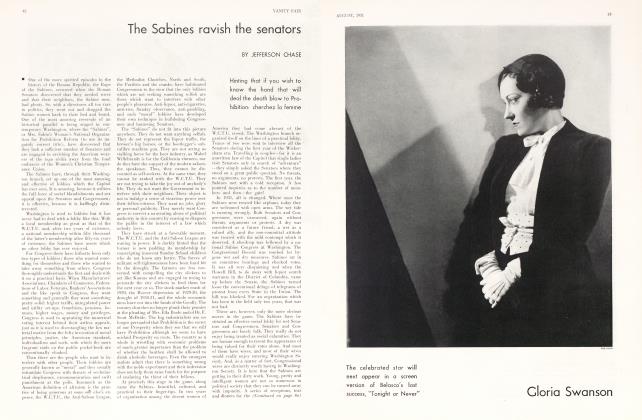

JEFFERSON CHASE

How political ambitions are aided in Washington by careful discrimination in accepting invitations

■ The first few months of the Hoover interregnum were relieved of tedium by the so-called Social War of Washington, between those who claimed, with Alice Longworth, that the wife of the Speaker of the House outranked the Vice-President's sister, and those who retorted, with Dolly Gann, that a perfectly good girl from Kansas who was official hostess for Charlie Curtis took precedence over Princess Alice. As a means of diverting public attention from the economic crimes which were being committed in the name of Tariff Revision, the incident takes rank with the trial of Landru, which enabled Clemenceau to handle the Peace Conference without interference from the French public. As a symptom of social immaturity, the controversy was distressingly naive. Dinner tables were divided against each other, wise-crackers exploded from the Golden Gate to the Bowery and the whole silly business was ended only by the death of Chief Justice Taft, a resultant armistice in the guise of official mourning, and the President's decision that he needed the farm vote pretty badly.

■ Gann vs. Longworth now belongs to history and may safely be left there, but the social scramble at the Capital which it dramatised for the public goes marching on. On the surface, this scramble seems ridiculous and inept. People who are so unsure of their social position that they have to protect it with "Keep Off The Grass" signs, have no social position worth considering. It all looks so deliciously Ward McAllister and so very buggy-days. Underneath, however, it is not social precedence which is at stake, but the much more serious matter of who is to wield the weapons of political power.

The world of entomology is thronged with insects which eat their way into the heart of an attractive situation, attractive—that is to say—to the insect. So, in general, is the social world. In Washington, however, political insects reverse the process and entertain their way into power. The lure of free food and, better still, free drink, is used to disguise the immutable fact that, in human society, you pay for everything you get. Here payment is made in terms of unsought intimacies, official toleration, surrendered independence. Once you have accepted a man's hospitality you are bound to him by a light but tenacious chain which enlists you measurably in his support. No bribe need be taken or received, no bargain struck, but when you have succeeded in pouring a mint-julep down the gullet of your adversary you have undermined his will—and hence his power—to attack you.

• For the basis of political power is the art of making and keeping friends. These friends may be made by an appeal to their mere material interest, to their prejudices, or to their personal self-esteem. A great political party is held together primarily by the first two; its leaders are enabled to cooperate by the latter method. Even the choice of political enemies is dictated by the necessity for making friends. When Roosevelt broke with Foraker, Taft with Roosevelt, Wilson with Jim Reed and Hoover with Hiram Johnson, it was because, in every instance, it appeared probable that the enmity of these men would win the President more friends than would be attracted by their support. The manner in which the breach is made is indicative of the ulterior purpose. Roosevelt's attack on Foraker rested solely upon popular prejudice against the Trusts, whose creature Roosevelt pretended the unfortunate Senator was, although he later acknowledged himself mistaken. When Taft scuttled Roosevelt's policies it was because he sought the support of the Old Guard Republicans who hated T. R. When Wilson tried to read Jim Reed out of the Democratic Party, he relied upon popular approval of the League of Nations to leave him relatively stronger than before. It is significant that the first open break between President Hoover and Hiram Johnson was the former's failure, by "an accidental inadvertence", to invite the latter to a White House dinner for the Foreign Relations Committee of which Johnson was a member. Whether accidental or intentional, the move was a clever one, inasmuch as it tended to make it appear that Johnson's subsequent opposition to Administration policies rested on nothing stronger than personal pique.

Let us return, however, to our saddle of mutton, our roast ducklings and our liqueurs. The basic fact is that social intercourse in political society is founded, not on personal congeniality, not on talent nor even on official position as such, but on personal profit. In Squeedunk, you invite people to dine with you because you like them; in Washington, you invite people to dine with you if you think they can be useful to you. You accept invitations as they may be advantageous to your policies. This holds true, from the third assistant stenographer in the Smithsonian Institution right up to and including the President. The permutations and combinations of the principle are innumerable, but the fact will remain so long as it is true that everyone in Washington wants something.

They all do. The subordinate wants more pay or promotion; his superior wants greater security in his post or the advancement of his policy; the Congressman wants reëlection, the Senator wants patronage; the Party wants power; the President, popularity; and the Supreme Court wants, in Mr. Dooley's heroic phrase, to watch the election returns. Foreign diplomats want useful contacts, nations want influence, lobbyists want favors, parvenus want recognition. They all want power, for, by a reversal of motives which is interesting in an acquisitive society, power rather than money is the hallmark of success at the Capital, and all of its denizens are striving for power under its multitudinous forms.

Hence the hospitality. There is need, of course, for delicacy of approach. The wife of the Congressman from the forty-sixth New York District does not immediately invite the Vice-President and Mrs. Gann to try pot-luck with the family next Saturday night. The young naval Lieutenant assigned to shore duty in Washington does not preface his assignment by asking the members of the General Board to a cocktail party. The newly appointed expert in the State Department does not, as a rule, attempt to secure the Secretary of State or the British Ambassador for his luncheonguest. Nor does the Washington representative of the Interstate Power Trust begin his activities by calling on the Justices of the Supreme Court. The Social War calls for wilier tactics and rr*re patient strategy than the frontal attack.

The first move of the ambitious official or political adventurer is to join the Metropolitan Club and, perhaps, a good country club as well. The first is almost indispensable, being freely patronized by the members of the Cabinet, by the higher diplomats and the more powerful Senators. The second is optional, as golf can be an embittering as well as a mollifying game and tennis leaves a scar of personal inferiority on one side or the other. At all events, a club is necessary to provide opportunities for contact on a plane of social equality which will supplement and modify the bureaucratic inequalities of the office or the iron-clad apparatus of the legislative committees. After the subordinate has rubbed shoulders with his chief a few times and has been properly introduced, the official inferiority complex begins to wear thin and the ice can safely be broken.

■ Slowly and cautiously the next step is taken, exchange of calls rather than cards, and simulated or real friendliness develops. Finally, a little dinner, not too formal, can be safely arranged. The essence of this dinner —which is the turning point of your campaign—is that, when you have secured your Big Shot, you should invite no other of his fellows or of your own. If you invite your equals you will simply be diluting your own prestige; if you invite his equals, you will be diluting his. Big Shots are like prima donnas, especially in politics, and are , consumed by chronic jealousy. The great rule is: don't try too hard or appear too eager.

(Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 76)

But that is the worm's eye view. From above it is more alarming. The superior looks down upon a mass of subordinates seething with ingrowing ambition, the loftier of whom would weep neither long nor loud if the superior broke his neck or could be forced to resign. Things sometimes go wrong with the best-arranged bureaucracies. A high official may guess wrong on public opinion, he may burn his fingers playing party politics, he may be delicately tripped from behind by an ambitious colleague and pouf! another little post to be filled by somebody else. A politician must keep his fences repaired, he must preserve his patronage, he must head off rivals, he must keep solid with the Party leaders, with Labor, with the Anti-Saloon League and with Business. A diplomat must watch his P's and cocktails. A lobbyist never knows when an investigating committee will be turned loose on him.

For the higher-ups, therefore, there is only one rule: Entertain, entertain, entertain always, frequently, discreetly and not too lavishly. They must build up some social inertia on their own behalf, must remain on "Ned" and "Charlie" terms with their bitterest rivals, must make sure that their wives call repeatedly upon the wives of their logical successors. Disarm them with drink, frustrate them with food, harry them with hospitality!

For these reasons dining for profit is the most prominent feature of Washington society. No one is immune from it. no one has to observe it more meticulously than the President.

If you scan the social notes carefully, you will see that among the White House guests have been such names as Amos V Andy, and such newspaper publishers as Adolph Ochs, just as Coolidge entertained Will Rogers and hobnobbed with Hearst. You get your answer if you tune in on the radio at seven P. M. or pick up the New York Times and turn to the editorial page. The White House correspondents are specially favored. Some of their ringleaders are constantly eating Presidential food and then supporting Presidential policies.

There are a few exceptions to this rule, but the exceptions, curiously enough, are the very men whose power is undiluted and whose influence unimpaired.

Even the exceptions, however, deserve no particular credit, except for intelligence. They have simply reversed the rules of the regular Washington game and instead of dining for profit are deriving profit from their refusal to dine for profit. By adopting the Catonian pose and appearing contemptuous of conquest by cocktails, they are obtaining power by a route just as sure as any which can be travelled over the embattled dinner-tables of the Capital.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now