Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowa kingdom without a king

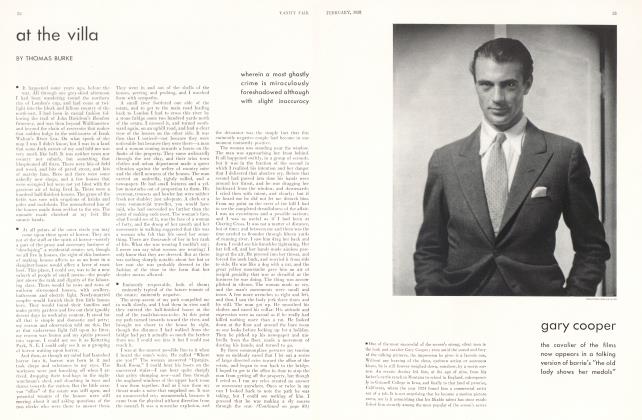

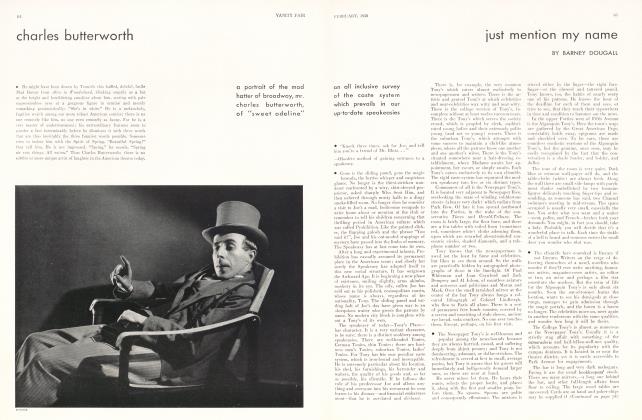

PAUL MORAND

budapest society is immured in its palaces while gypsy music is surrendering to jazz

I had not seen Budapest since 1920. At that time it was a war-like place, which had just been invaded from all sides by the enemy. The armoured cars of the Allies, still hearing bullet marks from recent battles, were lined up in the courtyards of the Ministries at Buda, lost in this new country; they were still camouflaged, and looked like checkered giraffes that had lost their long necks. Hungary seemed to have gone to pieces as a result of the war, and through every gap foreigners had come in. Italians and Jugoslavs had come from the south, French officers from Salonika, English soldiers from the Rhine, Americans of the Military Intelligence Department down from Vienna.

The mission cars, driven by soldiers in khaki or horizon blue, who had not yet laid aside either guns or trench helmets, moved about through the great crowds that gathered along the banks of the Danube as soon as summer came.

I arrived from Vienna by water; it was a very hot trip, and I was glad to find again, at the end of my journey, the old Austrian citadel of Mount Gellert, set on its cliffs, from which the martyr monk was thrown into the river in a barrel. I paid five francs—that is several milliards of crowns—for my room at the Ritz.

Every cafe, every hotel along the Donaustrand, had its orchestra out, its gypsies all in red and in gold boots, lounging over the cymbals they beat with their felt covered hammers. It was as if there had never been a war to the death. The slaughter, so lately over, seemed to have left no gap among these people who were so full of the joy of living: the students in Tyrolean costume, the athletes in running shorts, who were followed by laughing groups of girls in white blouses, fair haired, and tanned by the first summer suns. I thought then that Budapest had definitely resumed its gala air, its rôle of a city of gaiety, which, before the war, had given it a character all its own in Eastern Europe.

I know few cities so full of tradition as this. It was, for a century, for all the Balkans, the gateway to the East. For Roumanian boyars, for the rich Serbian swine dealers, for the Hungarian nobles, isolated for most of the year on their country estates, for the wild boar hunters, hidden in their castles in Czecho-Slovakia, Budapest represented all the voluptuous pleasures of city life: money thrown to the winds, nights passed, chin in hands, listening to the gypsies, while Tokay spilled unheeded on the tablecloths, amid the splendours of gold and scarlet decorations.

For Westerners, amazed by the magnificence of the costumes, the strangeness of the half-Asiatic faces, the passion of the dances, the homesick note struck by such barbaric musicians, after the Viennese waltzes, Budapest, so long a Turkish city, spoke with the voice of Scheherezade, and was, indeed, the gateway to the Orient. Old English sportsmen, former French diplomats, extravagant Austrians, taking a holiday, whispered in one's ear that one must not visit the Hungarian capital without being bathed by soft hands in onyx baths, or allowing one's self to be taken home by fictitious baronesses to rococo palaces, with pleasures in prospect that might have even interested Casanova.

Alas, that is all no more,—it is as if it had never existed. The war ended; then came inflation, the treaty of the Trianon, and, when Israel was King, the dark days of BelaKun. The country, so preeminently militaristic, was disarmed; the great estates were broken up by the Agrarian Laws. The peasants, survivors of the middle ages, rich in land, but poor in machinery, see Canadian wheat selling for a lower price to-day in Hungary than their own Hungarian wheat.

• In the immense palaces of Buda there is no longer wood enough to feed the high white porcelain stoves, and the Hungarians apologise for this by saying: "The Czechs and the Roumanians have taken all our forests from us."

If you sneeze, the Treaty of the Trianon is to blame. The Magyar nobles stay on their estates and no longer have any occasion to go in the Spring to the court at Vienna, where a Socialist republic has replaced the Empire. At the Opera, though the orchestra is still excellent, no one is dressed, the carpets are worn, the faded curtains weep, one might think, for the era of chignons and corsets. Nothing is sadder, nothing makes one feel more deeply the abyss between the time before the war and after it than the theatres, like empty frames left on the walls after the pictures have been sold. At the Opera the Imperial box, still crowned with the initials F. J., stays empty, like a recess in some desecrated church, from which the figure of its patron saint has been torn away.

A provincial calm is stagnant in the streets of the upper town, making them like those of the small Italian cities in the time of the Chartreuse de Parme. In Hungary there is no middle class, that supreme recourse of every country in times of distress. Trade, in the cities, is in the hands of the Jews. The walls of the citadel still bear, like the marks of smallpox, the scars of the Bolshevist bullets, but the revolutionists have taken refuge in Vienna or Paris.

Continued on page 92

Continued from page 43

You may still see illustrious ghosts passing by, like Berchtold, and all those little old men, last survivors of an administration that has disappeared, who signed their own death warrants on the day of the assassination at Serajevo.

Budapest, in spite of tradition, goes to bed early. Living is expensive, almost as expensive as in Germany. You soon realize that money is scarce, and you have to knock at many doors before you can get a bank note changed. What would have bought you a five story house in 1919 will barely pay for your lunch to-day. The older people, the pre-war people, who still reckon in kronen, never leave their homes; they cling to a haughty disdain for the plebeians, the contempt of an aristocracy, once privileged, for the crowd (which led a witty Berliner to say that the Hungarians were the only people who heeded the preachings of Keyserling). They speak a strange language which they insist is a virgin tongue, and unrelated to any other.

Shut up in its palaces in Buda, Society views the times with a jaundiced eye; the noble families, related by a thousand lines of kinship, consort exclusively with one another, and you see no one in the little deserted streets that look down on the Danube.

At Count B's, where I took luncheon one day, it was like a fine day in 1875. Draperies, heavy curtains with thick cords roping them up, fine old crumbling lacquers, and great dark spots on the white woodwork, from the stovepipes. On the piano the music was that of Bach and Handel, waiting to be played. A black-shod butler in a black coat, braided in black also, poured a topaz colored wine in Bohemian glasses and coffee in the tiniest of cups, like those in which the Chinese take their tea, while much old family silver shone in the faint light admitted by the lace curtains. In the antechamber an old Jaeger, in a green uniform covered with decorations and medals, wearing whiskers like those of Francis Joseph, waited, ready to summon the carriages of illustrious ghosts.

The baroque fa$ades and the grilled windows one sees from the Bastion, when one takes a walk there, under the trees, no longer smile. This country weeps not for one lost province, but for four—four Alsace-Lorraines! Hungary is not resigned to its fate. This is a proud land, not accustomed to resignation. All Hungary is reactionary, as is a part, but only one part, of Germany. And still . . . !

And still ... if there are no more soldiers in Hungary, there are still plenty of Honved officers; if there is no longer any seacoast, there are still plenty of admirals. And still . . . the upper classes have suffered less in Hungary than in the rest of Central and Balkan Europe, where they have been despoiled and annihilated. In the country the Magyar peasants, who have no use for ready-made clothes, and prefer to wear their sheepskin coats embroidered with spring flowers, still kiss the hands of their feudal lords. No matter what they say, the rich Hungarians are not shut up behind the grilled windows of Buda; you may see them at Monte Carlo and Deauville. And still . . . many American automobiles are sold here.

And still . . . the famous costumes of the magnates, with their zibelline collars, their gold braid, their feathered hats, their superb boots, those magnificent uniforms that bore their part in so many glorious charges of a world famous cavalry and in so many of Lehar's operettas are still there, and one may see even them today on many occasions. There are still, on the bridle paths and in the hippodromes, many of those superb horses that were the pride of the Hungarian army; the Roumanians have not quite emptied all the stud farms. Even though the cosmopolitan, Germanspeaking aristocracy, to which the Hapsburg monarchy gave estates in Hungary, has lost its real centre, which was the court at Vienna, the Magyars still keep their local nobility—the gentry, as the Anglomaniacs would say, which is the truest expression of the spirit of the country—and from which so curious a personage as Admiral Horthy was recruited—Horthy, almost as great a statesman as Count Bethlen, who is considered by many men of intelligence, worthy of being ranked among the first statesmen of Europe. Nor have the estates of Hungary been as badly cut up as one has heard, since the Festetics and the Estherhazys have retained immense domains. In May and June much money, many pengos, are thrown from the windows. In the summer hunting estates are let to Americans—and there are many quiet smiles at these hunters, coming from a land without game, who pay a dollar for every slain beast, since, after a few days of a battue, the heads are often counted by the hundred thousand. But then—don't British peers also rent their grouse moors in Scotland to Americans?

The Kingdom of Hungary? Yes— but where is its King, then? There is none, and that is precisely what is the matter with this country so preoccupied with its past. If a Hapsburg were recalled to the throne the Little Entente would mobilise. To be without a King is to go without the country's greatest memories. That is why this proud land, stripped not only of territory, but of its love of pomp and panoply, its traditional cavalry, its hero-worship, remains inconsolable, and, alone in all Middle Europe, refuses to accept the new times that have come.

That is why there are, at this moment, so many candidates for the throne. Among the legitimists, they swear only by the Archduke Otto, who is seventeen years old and lives in Spain—son of the former Emperor of Austria, Charles IV, and Zita. The Archduke Joseph Francis, who married a Princesse of Saxe, the Archduke Frederick, and, finally, the Archduke Albert, are also much discussed, to say nothing of the Archduchesses, two of whom, surrounded by a few royal supporters, live in the shadows of their palaces at Buda, in a rivalry producing a thousand amusing repercussions, and watch one another in the imposing drawing rooms where Society and the Diplomatic Corps have their being.

Continued on page 102

Continued from page 92

Poor, dear Hungary! Hungary, where the gypsy music gives ground daily and is surrendering, at last, even in the Admiral Club, to the nickelled artillery of saxophones and jazz.

There is one survivor of the past: the Hungarian policeman with his great sword, the ornament of all the night places, the last refuge of the picturesque.

Seated among wicker chairs, on the Ferencz Joseph Rakpatz, I heard an American family, newly arrived, trying to find its way in a menu printed in a strange tongue, whence there emerged only the familiar words goulash and paprika. The mother was reading aloud in her Baedeker that there was, at the Hotel Gellert, a bath with artificial waves, which made the children exclaim, wide eyed: "Mama, is that pool open?"

At the Park Club, refuge of the old nobility, portraits of Francis Joseph and the Kaiser, in red uniforms, still preside over the Salle des Fetes. The Ritz, Magyarized, is now called the Dunapalota, but it is still the Ritz. From my window I could see the Danube, at noon, on fire, as if it were a river of naphtha, flowing under majestic bridges with august names; in the morning I was awakened by the White Danube steamers, filled to the topmost deck by a crowd 'eager for bathing, for sunshine, and for excursions in the woods. Greener than the leaves, the great bulbous domes of the churches appeared on the horizon. This Danube is as great a river as the Mississippi or the Potomac, it is not one of those little European rivers like the Thames or the Seine, which are hardly rivers at all, and upon which everyone rides, irreverently, as if on a dog's back; the Danube carries its travellers with dignity, like the sea.

I happened to arrive at Budapest in that short season between Winter and Summer, so short that one can hardly call it Spring. In fact, as soon as the ice melts, as soon as the wintry winds from Galicia abate, the heat comes— a frightful heat, like that of the Sahara, that heat of the Hungarian plain which scorches everything except a few acacias among the immense wheat fields. Budapest, which lies in a wooded valley, though it is shaded, does not escape this universal heat.

After a few days of hot weather everyone abandons the city to go and lie on the artificial beaches of the Island of Ste. Marguerite, or to breathe fresh air on the high golf links, whence one may see the Danube losing itself in the endless plain of the black lands, where silos and grain elevators stand out, a plain ending only at the Roumanian coast.! In a few hours the Kovácz, the New York, the Hungaria, all the restaurants of Pesth, and even Cerbeaud's, the most famous pastry shop in Central Europe, are deserted, and it is to the summer New York, the Spolarich, the Sanatorium, the Restaurant Champêtre, with its green shutters, the Elizabeth Tower, the New Yorkon-the-Island, that one must repair.

With Summer a new Hungarian generation, which never knew the war, devoted to sport, athletic, clean shaven, like Americans, invades the beaches, plunges into the sulphurous waters and artificial waves, or, from the springboards, dives like champions. If Hungary has been mutilated, her sons and her daughters are restoring her, for after all the life of man is stronger and finer than that of any land.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now