Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowsermons in linoleum and good in everything

G. K. CHESTERTON

a development of the opportunities for thought in the man-made scenery that surrounds us today

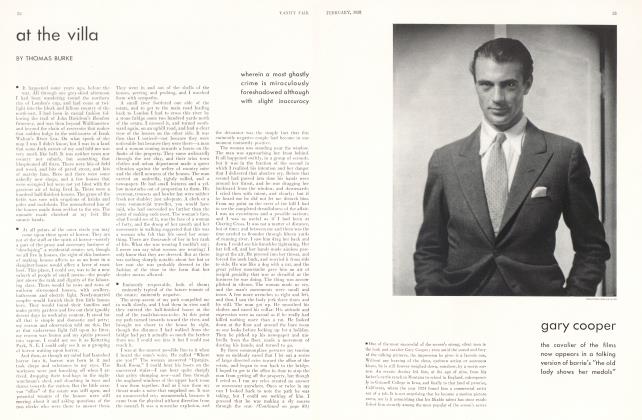

I hope it is not too egotistical to say that I am very seldom bored. I hasten eagerly to add that I am very often boring. Not once or twice in my rough island story, no doubt, I have been the cause of boredom in ethers. But 1 myself very seldom feel the exact sort of emptiness so described; I am not bored even when I hear the complete history of pre-historic man or listen to a Marxian Jew explaining the materialist theory of history. The difficulty of life seems to me that it is too full of distractions; and the details of anything we look at teem and beckon with bewildering questions. I have taken a sort of test case of sitting in an empty waiting-room in a remote railway station in the rain, with nothing to look at but the pattern on a sort of linoleum or oilcloth; a pattern printed in dull green on a sort of drab. I looked at it until there arose in my imagination the strange and mysterious figure of the man who made it; the man who (perhaps) really wanted it to look like that. There rose with him many other mysteries; as the obscure and obstinate way in which men ornament things that they never look at. It is remarkable how few really plain things there are in the world. Man always seems to leave his mark, in the shape of a strip or a moulding or something sublimely useless. But there arose also a meditation that led me back many years to the beginning of many things.

There is always at the back of my mind one old original controversy. On the one side are those who regard all pictures as patterns. On the other side, which is my side, are those who tend rather to regard all patterns as pictures. For that, I think, was the real question at issue in the first ink-slinging quarrel in which I began to sling ink. In that particular phase of the quarrel my opponents were the Decadents, or aesthetic pessimists of the period of Wilde and Whistler. And the upshot of their philosophy was, as I have said, that all pictures were patterns; or as Whistler would have put it, arrangements. The artistic theory was not, of course, confined to the art of Whistler; it was applied equally to the art of Wilde. It was applied to the art of men immeasurably greater than either; and the point of it was that all masterpieces could be contemplated in a spirit that was called "Art for Art's Sake", and with hardly more moral emotion than the same critics would have given to a turkey-carpet. Othello was not only a study in black and white but almost a scheme of black and white, like the scheme of a chess-board. Macbeth was a conflict for Macbeth; but for the critics the crossing of the swords in his duel was almost as decorative as the crossing of stripes in his plaid. Dante's Inferno was an arrangement in black and red; and even his Paradise was only blue with white spots.

Now I felt even in my boyhood a reaction against this; a perverse reaction in precisely the opposite direction. While my elders were seeing diagrams in the coloured composition I was like a child still seeing faces in the carpet. It was my instinct that the imaginative life would rather be increased by finding moral emotions in wall-papers than in finding decorative schemes in dramas. It was my temptation to see a black and white pattern; and indeed the very example I have given is an accident in my favour; for the chess-board is itself a battlefield. I tended to see the crossing of swords even where there was nothing but the crossing of stripes. It might well be suggested that there is a touch of madness in this notion of common curtains, dancing with figures like a wizard's tapestries, or common carpets beginning to crawl with life. But on the whole I am prepared to defend the sanity and soundness of my own revolt it against the merely ornamental school. I think it rests on a much sounder psychology than their own psychology of art for art's sake. It It rests on the psychology of association and It the unity of the mind; whereas theirs had really to imagine an imagination that should be in water-tight compartments. I maintain that when we see a chess-board pattern we do think of chess; and then when we think of chess we do think of its chivalric, historical and philosophical interest. I maintain that when we see a Highland plaid we do think of Highlanders, and therefore of claymores; and that when we think of claymores we do think of old romances of feud and faith and of loyalty to chief or king. I deny that any decadent ever so detached his artistic sense as to look at a tartan without thinking of Scotland, or to look at a chess-board pattern without knowing there is any such thing as the game of chess. It involves an impossible constriction of the imagination not to entertain a moral suggestion, which a material object obviously suggests. All sorts of nonsense is talked now-a-days against what is called a novel with a purpose. What sort of monstrosity would be a novel without a purpose? It would be more horrible than a headless horse.

Continued on page 84

Continued from page 55

But it is not only the novel or the fable that is involved here. I am concerned at the moment with what is called merely decorative art; and I am pointing out that even that art is not merely decorative. We do, whether we like it or not, indulge in moral meditations over hearthrugs and wallpapers. The tone of colour, the type of ornament, do in fact pass into our thoughts, and even into our ethical thoughts. The patterns are not merely lines; they are forms; generally the forms of flowers or fruit or foliage; but anyhow forms that we recognize and forms about which we already have feelings. There ought to be some story somewhere, though I have never read it, about such curtains and tapestries being alive, and the creepers creeping up them and the carpet changing colour with the seasons. Anyhow it is certain, and easily tested, that we do have more general associations with these arbitrary recurrences that make the background of our lives.

Suppose an ingenious man of science had his wall-papers covered with magnified monstrosities of the animalculae shown by the microscope in a drop of water. He might argue that it was an agreeable change from the banality of flowers; he might even quote Mrs. Meynell who once complained of the monotonous pattern of flowers. He might also argue as subtly, though I fear less successfully, that there is really no difference between the animalculae and the flowers. The shapes of the miscroscopic monsters (he would urge) are by no means ugly in themselves. He would say, surely not unreasonably, that wall-papers covered with flowers and foliage should he confined to the private apartments of a botanist. Such organisms as crawled about his own walls were the only ornament proper to the parlour of a bacteriologist.

I should like to have tigers and panthers fighting all over my wallpapers; elephants and mammoths and anything that is more monstrous than mammoths, rending and towering and trumpeting and turning my private parlour into a jungle ravaged by a tornado. Personally I do not object to any of the other suggestions. I am willing to embrace the radiant shapes of the monstrous microbes. I do not object to skulls, which really wear a very cheerful and gratified expression, like goblins with broad grins. All this I am willing to allow; but the more we allow for it, the more we shall come back to the essential truth. Whether we like or dislike the associations, we do feel the associations; and we cannot possibly see the figures without feeling the associations. We do cover our curtains with blossom because most people have pleasant associations with blossom. We do not cover our curtains with microbes, because few people have pleasant associations with microbes. We do cover a wall with roses rather than skulls because only a chosen few are really cheered up by skulls. And in the case of the organisms—at least it is true that, in abstract decoration, there is really little to choose between an animal and a vegetable form. The point here is that no decoration ever is abstract decoration. It is for that reason that even the man of science will, in fact, continue to cover his bedroom with a pattern of flowers instead of a pattern of fleas.

Now this is what I mean when I say that a pattern can be a picture. The psycho-analysts would say, I suppose, that a picture appeals to the consciousness and a pattern to the subconsciousness. Only they always seem (for some reason I cannot follow) to suppose that the subconsciousness is an abandoned blackguard; in which case it seems rather odd that he should have such an innocent taste in bedroom wall-papers, and should be so easily soothed with little daisies all in a row. If his one submerged and insurgent desire is to paint the town red, why does he generally when he officiates as house-painter, paint it white or green or at the utmost pink? Anyhow decoration can certainly be called the background of life, whatever may be called its subconsciousness, and the interesting matter here is that at certain moments the background can become the foreground. It is so at such moments as those in which I have sat staring at the corner of a piece of linoleum.

When once we understand that our souls and our moral senses have sunk into all this furniture and upholstery also, as well as into books and pictures, we can always pass an entertaining hour trying to get them out again. The incantation may not be perfectly successful, any more than the attempt to extract the sunbeam when once it had got into the cucumber. But it will always be interesting to say to oneself, in staring at the most lifeless pattern: "It was the mind of man, mysterious and unsearchable, that put those three brick-red triangles in the middle of that yellow panel." Or "A man really meant something when he sprinkled all those little pea-green dots; even if what he meant was something so subconscious that he hardly meant to mean it." This interest in the most insignificant designs and decorative trivialities gives a vast and novel interest to life. The disciples of this true doctrine will be found standing about the streets, in attitudes of arrested and abstracted attention, with their eyes rivetted on the moulding on a lamp-post, or gazing at the knobs on the top of a railing. They will be with difficulty introduced into a house, owing to the paralysis of contemplation that may seize them at the sight of the doorscraper, or the coloured stripes on the oilcloth in the hall. Nevertheless there should be, I think, a limit to their ecstasy. There is a reasonable case against bad decoration, though it is seldom reasonably stated. Perhaps it might be reasonably stated thus.

Continued on page 102

Continued from page 84

Seriously speaking, I am willing to admire even what is not admirable, so long as it is admired. If the landlady of a poor lodging-house is really fond of her coloured oleograph or her wax fruit under a glass case, then I will (so to speak) raise a riot and perish sword in hand in their defense. Her parlour is much belter worth fighting for than her parliamentary vote. But when all this is appreciated, there does remain I think a certain amount of ornament in such surroundings that is trivial in intention as well as in effeot. Much of the minor ornament is machine-made, and is peculiar to an age of machinery. That is where the real distinction comes in. I could lose myself in what the dramatist has called rosy rapture over counting the pink pips on a wallpaper, if I really thought that anyone had shared my rapture. I could rejoice in a brick-red stripe on a peagreen fence if I really thought that anyone had wanted it to be red on green. But I think it cannot be denied that, with the age of machinery, there entered a certain mechanical and mindless habit in all these things. And with that we come to a point of considerable historical interest. It is not that all these strange shapes and colours are not interesting. It is that the earth brought forth a still stranger race: of men who were not interested.

This is the real case against the ugliness of much of the detail of modern life. It is a case quite different from that of the mere aesthete, because it concerns the historian and the philosopher. It is that we have recently passed through a particular age which future ages will see as one of artistic ascetics, and even of artistic suicides. But precisely because their ugliness was unnatural, they did not succeed in being completely ugly. They only sunk deeper into the subconsciousness their blinded and thwarted thirst for beauty. And this does not make barren the more mystical contemplation of their strange ornament; it only makes it more difficult. It is still none the less true that everything that was made by a machine was ultimately made by a man. It is still none the less true that there is a mind somewhere at the back of every dingy diagram, and a moral atmosphere surrounding every futile excrescence. The art that emerged in holes and corners; in spite of the scorn of art, is none the less a fascinating feature in the history of art criticism; and there is nothing human that is not as deep as the divine. For which reason I shall go on looking at the little piece of linoleum, until I have got more out of it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now