Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

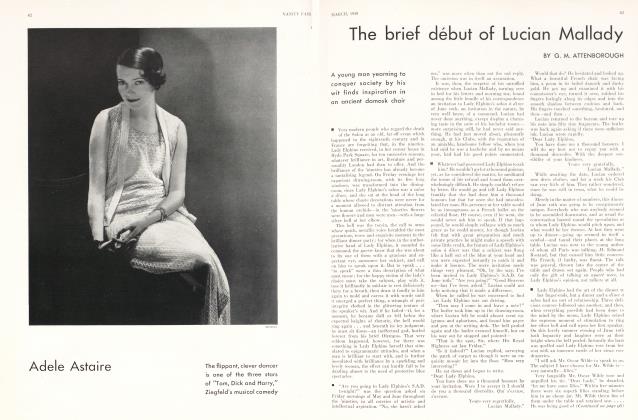

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEccentricity no crime

HENRY MORTON ROBINSON

A spirited defense of the filigreed manner, proving that even a little lunacy is better than none at all

■ The eccentric not only gilds the lily—he carries it in public. Or maybe it's a sprig of wild olive, or a chameleon, or a musical walking-stick with an illuminated handle that he carries. Or yet again he may carry none of these, preferring to play the passive role and be palanquined about town in a landau drawn by seven mystical zebras. I once knew such a passive agent; he lived, as I remember the case, in Selma, Alabama. His zebras were (as we afterwards discovered) nothing more than army mules handed over for post-Cezanne treatment to a designer of barber-poles. But the effect on the mules—and on the public— was so paralyzing that the owner was reputed to be fabulously queer, rich and clever; also demm'd bold, exotic, and interesting. In short, eccentric. He borrowed money on his eccentricity; he became a candidate for senator on the same platform, and was defeated only when the mulish nature of his zebras was exposed to the electorate of the great state of Alabama. In the sound and fury of his campaign he forgot to get his mules repainted!

What the United States really needs (and Mr. Stuart Chase will pardon me if I seize the baton from him here) is a few genuine eccentrics, flaunting the authentic stripes of their species at the head of our mulish contemporary parade. A few men and women to whom the doldrum monotony of life is so ghastly that they are driven to frantic shifts and off-centre expedients, merely to get through the long, long day. Expedients such as—well, ordering pemmican at the Park Lane, or raising a Dundreary and twining asters in it, or producing Seven Keys to Baldpate in modern clothes. Or running for Mayor on a Single Standard ticket, or not writing sonnets on the perfectly glorious explorations of Admiral Dicky Byrd. Or in fact anything that will, to a comforting degree, relieve the dust-lipped tedium of muleteering, and centricity, and good wholesome fun.

By "eccentric" I do not mean the sort of person who has lived in seclusion since 1871 in the grimly mansarded house at No. 2 Gillingwater Street, and who has his groceries slipped in through the mail-box just because the Board of Selectmen won't designate his house as No. I Gillingwater Street.

By eccentric I mean a person who sweeps in a brilliant parabola across the dun sky of our lives, deviating in centrifugal swoops from the Republican norm of existence. I mean Paganini, Hetty Green, Yilliers de L'Isle Adam. A person who by reason of his wildly filigreed manner attracts the attention of the great world, and after attracting it, tosses it back as gracefully as a sequin tosses back candle-light. Your true eccentric is a rare soul who swings the world like a trinket at his wrist, and never cares whether the chain breaks or not. A mad, sweet original, hacking at the butcher blocks of convention with a pretty poignard, dipped in triple essence of verbena and covered with a long lace cuff.

"But what good," bleats the pragmatist, "are eccentrics?" A lot of good. They point out what the rest of us have too evidently forgotten—the delightfully erratic possibilities of human life. They get far away from the good, the true, and the beautiful, substituting for this dour trinity the rarer qualities of the rare, the cuckoo, and the courageous. Instead of acting like a bunch of six-day bicycle riders wearily grinding out the day's lappage, the eccentric pedals to the edge of the cosmic bowl and capers magnificently on one wheel while the race of men drone by.

∎"They caper magnificently on one wheel," I said. And by magnificent capering I mean the kind of thing that has been done, all too rarely, by such caperers as Baron HardenHickey, Gerard de Nervhal, Gabriele D'Annunzio, Timothy Dexter, Harry Lehr—and of course the two incredibles—"Dizzy" and Oscar Wilde. Each of these men had a charming act of his own, something that he could pull out and show the world on a dull day. D'Annunzio, for instance, always carries a hundred umbrellas with him whenever he goes to London. "There is so much moisture there," he is fond of explaining. At a certain stage of his career, Benjamin Disraeli refused to drink out of anything but an opal cup, filled from a crock of gold. Gerard de Nervhal stopped Paris traffic regularly by leading a deep-sea turtle down the boulevards. When his friends remonstrated, de Nervhal flamed into a rage: "Why not lead turtles?" he argued. "They do not bark, or tug at the leash; furthermore, they know the secrets of the deep." Bernard Shaw's little trick of carrying on all his correspondence with post cards puts him comfortably within the eccentric pale. Harry Lehr, one of our most successful American entries, reached a high level of distinction by handcuffing himself to Mrs. O. H. P. Belmont and then swallowing the key. Yilliers de L'Isle

Adam was never at ease unless he could have a decayed quince about his person. But I feel that I had better stop here.

Unfortunately we have in America no living eccentric of first rank. But that doesn't mean we never had any. I can think of several of the weird brethren, but by all odds the weirdest and most delightful of the troupe was Baron Harden-Hickey, Philosopher of Suicide, King James I of Trinidad, and Pretender to the Crown of Honolulu.

■ As a chitling youth James Hickey left his native California and went to Paris—the Paris of Napoleon III, of Murger and the Second Empire. Here Mr. Hickey became an editor, a novelist, the most expert swordsman in a dozen cafes, and an inveterate bringer of lawsuits and challenges. Before he was twenty-five he had engaged in no less than forty-two lawsuits and seventeen duels. He lost all the lawsuits and won all the duels— in fact he was quite the model for the bloods of the town. Retiring for a month to a monastic cell, he composed a most instructive handbook entitled Euthanasia, or the Ethics of Suicide. Into this jolly cahier he incorporated all the rules and regulations concerning self-destruction, together with the proper times, genteel places and accepted modes of giving one's self the rap. He recommends no less than eighty-eight poisons, and fifty-one instruments, including embroidery scissors, fruit-reamers and (somewhat ahead of his age) flyingmachines. And no one since Petronius has ever gone in for such exquisite artery-severing as Mr. Hickey. In the refinements of bloodletting he was a self-confessed wow.

For championing the Holy Roman Empire in a dashing pamphlet he was rewarded with the title of Baron. This far the Baron had successfully avoided the routine of workaday living. But eventually his duelling and litigation began to pall, and our nobleman began to affect a kingly air. As a step in the right direction he began to cast about for a Queen Consort. And he found her in the attractive person of Miss Annie Flagler, daughter of the late John H. Flagler, the Standard Oil magnate.

All that the Baron needed now was a kingdom, and he diligently set about digging one up. Instead of striking into George Barr McCutcheon's patented territory "west of the setting sun," the Baron seized the island of Trinidad, a derelict rock lying seven hundred miles off the coast of South America. This rock was inhabited by nothing but birds, turtles and enormous landcrabs; its principal product was guano, and it had no harbor. Incidentally, it was claimed by both England and Portugal. But in spite of these wasps in the ointment Baron Hickey proclaimed himself James I of Trinidad, and took unto himself all the appurtenances of his kingly office. He manufactured a coat of arms, .a royal seal, and thousands of postage stamps. And in order to keep in touch with the great world, he hired a Minister of Foreign Affairs. The Trinidad legation was established at217 West 36th Street, and served as King Hickey's headquarters whenever his Royal Highness came to town. Of recognition he got none, but of publicity—plenty. In fact, the King's antics, bulls, and manifestos were all a part of the day's fun in the New York of the nineties. Broadway had a real comic opera king who did not hesitate to rap his scepter over the sconce of any luckless lackey who happened to offend him. Richard Harding Davis, at that time a mere reporter on the Evening Post, was assigned to cover the King, and admits that Hickey almost sold him a partnership in the guano demesne of Trinidad. Which almost proves what we've long suspected about Mr. Davis. . . .

Continued on page 110

(Continued from page 47)

Of course England had to spoil the fun by claiming the island as a cable station. King Hickey was then offered the crown of Honolulu, but he wasn't satisfied with the Hawaiian army, which consisted of 160 men and boys. So the negotiations broke down. And just about this time, Mr. Hickey fell to re-reading his own book on suicide. It so intrigued him that he decided to put his theory to the test. Which he did—not with potent ferments, nor yet with exquisite devices. He took an ordinary .38 caliber service revolver and blew his brains out.

But King Hickey was not the greatest of American eccentrics. The record shows that he was completely outpointed by an earlier and loonier eccentric,—one Timothy Dexter of Newburyport, Massachusetts. "Lord of the East, Lord of the West, and the Greatest Philosopher in the Known World" was the mpdest legend Milord Dexter caused to be inscribed, in gilt lettering, on his house. In front were several wooden statues, richly carved and gilded. These wooden figures represented George Washington, Moses, John Hancock, and Timothy Dexter himself.

Milord Dexter, with the true eccentric flourish, must have a poet laureate so he appointed one Jonathan Plummer, a carpenter by trade, to celebrate his deeds in deathless verse. The Bard certainly earned his keep! Every time Lord Timothy Dexter went to Concord or Chester with his Mexican hairless dog, Laureate Plummer would sit himself in the poetical stocks and rip off an ode against the day of his master's return. This ode was duly printed and spread broadcast over the town, causing the best Newburyport families to gnash their teeth at his presumption. But the eccentric Dexter cared not at all for these gnashings, and straightway developed fresh idiosyncrasies to keep things hot for his enemies and amusing for posterity.

Which is just what he did. Seating himself at his whale-bone escritoire, he wrote a blistering pamphlet against the world at large and his Newburyport neighbors in particular. This pamphlet, entitled A Pickle For the Knowing Ones is one of the curiosities of literature, and is utterly illiterate, hair-raising, and unabashed. Dexter could neither spell nor punctuate, so he misspelled all the words and left out all punctuation. But—and this is the true eccentric stroke—he put scores of commas* periods, and question marks on the last page of his pamphlet, and bade the Knowing Ones "salt and pepper the book to their own taste."

Evidently he took the last kernel of eccentricity with him, for he has had no successor. The current century, original in everything except politics, vice, and manners, has produced no eccentric worthy to hold a warmingpan to Lord Timothy Dexter. With all our Chambers of Commerce and Senatorial committees working at top speed, I doubt if we could generate a single specimen of genuine high-C eccentricity, a real zebra-driver, or a public lily-carrier. Nor is the reason for our failure hard to find. Eccentricity, as I conceive it, is the emergence of a rich and decadent ego functioning in a world where all other egos have been choked by tedium and routine. So far from being a crime, eccentricity is the very index of what behaviour should be. When Prince Albert sucks the head of his cane as he promenades, or when Mr. Clive Brook appears for breakfast wearing an Ascot, or when Oscar Wilde first puts a gardenia in his lapel—they are all emerging from the grey shadows of tradition into the clear light of eccentricity. They become powerful and generative influences in the lives of ordinary men, aristocrats of deportment, lonely and original personalities. We have no such personalities in America today. And the obvious comment is: "Oh that we had!"

Personally, I have always regarded Prince Hamlet as the highest lift of mortal eccentricity. In his royal person he combined the ingredients of the perfect eccentric: he was a dandy, a wit, a snob, a swordsman, a morbid philosopher and a completely histrionic madman. His wild and whirling words confound the duller wits of his confreres—notably Polonius, who is given out as the model of conventional wisdom and sanity. The ultimate test of the eccentric philosophy could be compacted into a neat question, a very simple and a very leading question, viz.:

"Who would you rather spend your evenings with:—Hamlet or Polonius?"

A vote for Polonius is a vote for the septessence of boringhood; a vote for platitudes and key-rings; a vote for Babson, Boole, and Borah. But a vote for Hamlet is a gesture in defense of skull-duggery, word-play, sword-play, ghosubaiting, lunacy, daffodils and corruption—

Will the secretary please pass around the ballots?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now