Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowExit the Swell

HENRY MORTON ROBINSON

The true definition of dandyism, with a pause to shed an immaculate tear for its departure

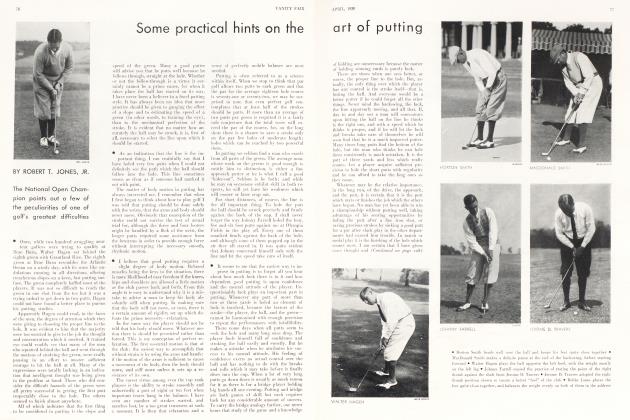

Dandyism started out to be a philosophy of dress and ended up by being the bestdressed of philosophies. It began by making the world cravat-conscious, and now—in its best moments—it is consciously using the world as a necktie-rack. By taking thought to the proper height of its hat-crown, dandyism has added a full cubit to human stature; and by insisting upon the primacy of elegance in mortal affairs it has given a brilliant rouge to the foolish face of society. Quite briefly, dandyism is the perfect formula for the civilized life, and the final triumph of manners over man.

"I hate dandies!" bellowed the late Joseph Pulitzer, stamping about the after-deck of his yacht as it emerged from a young hurricane headed straight for Florida. Then he whimpered plaintively: "They disconcert me so!" Whereupon he flew into a nautico-editorial rage and fired a trained secretary in mid-ocean, not because the secretary had failed to use the subjunctive in a contingent clause—no, no, this particular secretary had his syntax down cold—but because he had displayed a dandiacal elegance of manner in the recent hurricane. In fact, he had a better hurricane manner than his employer, and Mr. Pulitzer was just enough of an old meany to resent it. When a storm blew up he liked to see his secretaries scud for shelter or cower sickishly abaft the beam. But this particular secretary, being something of a dandy, declined to scud or cower. He refused to strike his urbane colors for a mere hurricane (though he afterwards told me that he hated oceans even in the best of weathers) and thereby achieved that victory of the formal over the normal which is the watermark of the real thing in artists, saints, conversations, and dandies.

■ I am glad this hurricane question came up so early in the semester, because it foreshadows what I shall be at some pains to prove:—that a dandy is as much a dandy in a simoon as in a saloon. Yes, typhoon or drawing-room, afoot or horseback, four-flush or full-house, the dandy is stamped with the faint yet unmistakable seal of his race—a stamp which all the tides of adversity cannot wash away, nor all the fires of hell's own poverty quite obliterate. For he has, above everything else, that charming faculty of being graceful under pressure, a faculty of which average citizen wots nothing at all. Pinch most human beings and you get a squeal. Twist the arm off a college football-player and you get a sickening grin. But crush the dandy to earth and a mildly unperturbed smile is all you'll possibly be able to get for your sadism.

Somehow a huge mistake concerning dandyism has crept into the record, and as a result this philosophy of the exquisite is popularly confused with a branch of the cloak and suit business. Well, I concede the fact that dandyism is interested—mightily and expertly interested—in the how, when, and what, of male attire. Thank heavens it is! When dandyism throws its infallible arm protectively about the designing and wearing of male clothing, mankind is spared the ghastly fluctuations and absurd anomalies that beset women's wear. For while women's clothing is originated in stuffy "ateliers" (yeah?) by professional designers who clip and be-flounce their product quite arbitrarily, mens' clothing is the quotient of a few choice spirits sending a divisor of utility into a dividend of creative leisure. Take for example that rainy day when Lord Raglan first appeared in a long, loose-fitting coat at Sandringham for a few practise shots. I claim that Lord Raglan at this point was a very complete and masterful dandy. No one had ever worn such a coat for such a purpose, but as it soon turned out, it was exactly the right coat for shooting in wet weather. It took all the practical and esthetic experience of a shooting nobleman to invent the raglan—but it took neither brains, nor experience, nor good taste for ten million non-shooters to wear that garment. Which illustrates the vast gulf that yawns between the aristocratic reality— which is dandyism—and the plebeian aping of that reality—which is foppery.

■ Dandyism is always right. The true dandy can do no sartorial wrong, even though he cuts directly athwart the usage of generations of well-dressed men. Consider for a moment the vogue of the soft-collared shirt, a fashion that would have been most distressing to the exquisites of Natty Willis's era. The softcollared shirt originated, I believe, with a slight irritation on Mr. Edward Windsor's neck. On any other neck it would have been a boil, but on Mr. Windsor's neck it was strictly bulletined as a "dermal irritation." Now the generally-worn stiff collar chafed the Windsor boil, and consequently a soft-collared shirt was prescribed by the assembled doctors. Of course these doctors, being guileless men, didn't realize what would happen. But when the young Mr. Windsor appeared at a levee in a soft collar and a plain black tie (a gesture of mourning for the deceased Dowager) the world of well-dressed men gasped and went out to buy huge stocks of soft washable shirts and plain black ties. The result, up until the time subway conductors reversed it by wearing plain black shirts and white washable ties, was as charming and informal a touch as was ever given to manly apparel. I still see men under the spell of white shirts and black ties, but they are not quite the last cry just now. Since the dermal irritation period Mr. Windsor has worn, to my knowledge, blue shirts with burgundy ties, and fawn shirts with burnt orange ties. I fear he is a Hamelin piper, this young Windsor, who sometimes uses his dandiacal pipe maliciously in order to make the necktie public dance to his piping.

■ But there is more to dandyism than neckties and weskits. Oh, a great deal more. What the rose window is to religion, these are to dandyism—the external symptoms of a deepseated condition, the burnished trappings of a powerful inner stimulus to perfection. For I conceive dandyism in its highest reaches to be a philosophy of perfectionism—a disciplined and deliberate effort on the part of extremely civilized persons to attain a kind of excellence that has hitherto been given too little attention in this or any age. A kind of excellence closely resembling the dream of Epicurus, fearless, aloof, and marked by all the delicate moderation which the epicurean ideal implies. A difficult, hardy excellence, not limited to clothing, food, or furniture, but penetrating to the very core and radix of life. A kind of excellence, if you must have examples, achieved by Henry Adams in his youth, Arthur Schopenhauer in middle life, and George Santayana in his old age.

In personifying this excellence I have named three philosophers, and for the life of me I cannot think of dandyism in any other terms. At the present time I can mention no living American who has more than a trace of it in his make-up. John Drew was probably the last exponent of dandyism to move among us; his complete urbanity concealed what ever spiritual deficiencies he may have had. Personally, I think he lacked nothing, and that he deserves to be ranked with the superb specimens of all time. Huneker too, had his moments. He was a grand liver, exhibited a genuine flair for clothing, and knew the world as most men know their club menu. A steeplejack of the seven arts (gastronomy he declared to be the eighth) he was forced to push his pen too briskly for hire, and thus fell away from true greatness as a dandy.

Coming down to the present scene, what can we cull from the mediocre players that clutter the stage? Mr. James J. Walker, Mayor of New York, is popularly acclaimed as a dandy, but his unfortunate habit of making speeches has dulled the edge of his intellect, and clogs the development of his latent will to dandyism. Besides, he would have to read more, which would be fatal to his career as a politician. His minion, Grover Whalen, is a middling police commissioner with a boutonniere complex. But his movie-tone conception of higlif in a top-hat always hampers Mr. Whalen when he essays the free-hand brummel manner. Rudy Vallée would have to have the whole idea explained to him. Dr. Harvey Cushing, brain specialist and biographer of Sir William (Equanimitas) Osier, has the potentialities of a verry parfit dandy. But fortunately for humanity he is too much interested in trepanning skulls and draining cranial quagmires. He could have been at least a colonel in any dandiacal regiment. Jack Barrymore had excellent masters, and approximates dandyism more nearly than anyone on the Hollywood trapeze.

Continued on page 88

(Continued from page 66)

In politics, that devious track on which so many English dandies have shown their mettle, we have the sorriest bunch of entries ever gathered into one stable. With the exception of Mr. Nicholas Longworth and one or two others, I cannot think of a single Congressman whose hat-band is not sweaty, whose neckties are not speckled, or whose language, manners, carriage, outlook, and habit of neck-shaving do not suggest a selling-plater on a mud track.

No wonder a captain of the valet industry left Washington muttering: "Let me press the pants of a nation; I care not who makes its laws."

But all this is a far hail from my original thesis, which attempted to prove that dandyism is the only philosophic habit for a gentleman. The thesis is still demonstrable, and while I can point to no eminent examples of its truth, I think now of one man in particular—a simple fellow really. His income is modest, but so are his wants. I fancy he has never owned more than thirty suits of clothes, or forty pairs of shoes, or fifty hats at one time. But it is his utter histrionism in performing the simple acts of life which gives me the impression that he has solved the riddle of boredom. When he offers you a cigarette he extends his gold ciborium with a sacramental gesture, as though he were at least a papal nuncio, and you a royal communicant. But it is more than a gesture with him; it is his only reality. He is the very axle of celibacy, and at the age of thirty, five is on his way to being the most civilized man in the United States. The only thing that can possibly check him is marriage, which has ruined more dandies than all other causes combined.

A last warning. For every authentic case of dandyism there are a thousand counterfeits in circulation: the fop, the buck, and the beau. But they are merely veneered hat-racks, perambulating shoe-trees. If at first one such seems plausible, ask him the following question: "Honestly now, what do you make of Plotinus's seventh Ennead?"

By his answer you shall know him. If he answers incorrectly, he is a poseur and should be dropped from the rolls. However, the only difficulty with this little question is: You have to be something of a dandy yourself to know the right answer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now