Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRed love

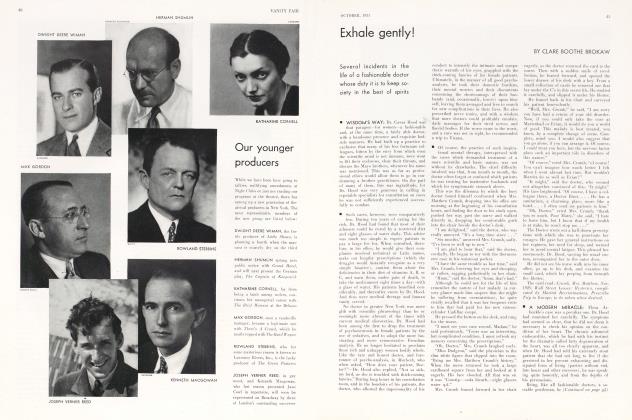

MAURICE HINDUS

A consideration of the emotional and physical status of young women under a Soviet régime

■ Russia is a hidebound dictatorship under which freedom of speech, press, and assembly, as these are understood in the outside world, are suppressed. Yet human beings will remain human; dictatorship or no dictatorship, they live, feel, struggle and aspire. The Soviets are bent upon wiping out the old world, but at the same time they are striving to build a new one, and trying with all their might to develop new men and women who shall be worthy to inhabit their new world. The energies of the entire nation have been ruthlessly drafted to this end. Outside it, nothing and no one matters, but within its limits, however narrow these may seem to the western world, men, and especially women, find ample opportunity for self-realization. For no country since the beginnings of civilization has bestowed upon its women as high a state of individual independence as does Soviet Russia.

This independence of women is no mere theory or moral precept, hut an all-pervasive reality, an integral part of the Russian woman's everyday life. She loses caste if she fails to avail herself of it. She invites scorn and derision if she persists in being merely female, with household affairs and domestic bliss the chief interest of her life. Those daily decreasing instances in which ancient heritage proves a more powerful influence than revolutionary procedure, are pointed out to the youth of the land as examples of spiritual decadence which should he stamped out. In high school and college, in the factories and on the farms, woman's influence and position in Soviet society is constantly being strengthened and advanced. Hence, the ever increasing penetration of women, especially of the younger women, into every phase of human endeavor. It is true that in the three highest ruling bodies—the Political Bureau, the Central Executive Committee of the Communist Party, the Council of Commissars and of the Cabinet—women either have no place at all or are only meagerly represented. But it must be remembered that the number of educated women who have merged their destinies with the revolution is after all much smaller than the number of educated men, and even under a proletarian dictatorship, the higher the office, the greater is the need for commensurate cultural equipment.

With the exception of these governmental bodies, however, women have found their way into every field of national effort. The time is not distant when, numerically at least, they may dominate the medical profession. Already nearly two-thirds of the students in the medical schools are women. In the judiciary and in the Soviets women have won places of prominence. They are likewise conspicuous in factory management and in the operation of the big new farms, and some of them have shown great ability in engineering and architecture. Women are exempt from military service, yet they are members of the volunteer war organizations, and join the men at target practice on the numerous rifle ranges throughout the country where the populace is being trained in marksmanship. In the endless parades of which Russians are so fond, the girls, gun on shoulder, march beside the boys. It seems safe to say that in any future war Russian women will be active, not only behind the lines but on the battlefront itself.

Reared as the Russian girl is in this atmosphere of economic independence, of equality with men, and of social responsibility, what, it might be asked, is happening to her femininity:' What kind of a love life does she have or look forward to? As daughter, mother, lover or wife, wherein, if at all, does she differ from the women of other lands? And how does she react to the stupendous equalities and responsibilities with which the Soviets have endowed her?

Perhaps the most marked change which the Russian girl has undergone is in her attitude toward her parents. "Love thy father and thy mother" has little meaning for her. This is true not only in those cases in which the daughter has been converted to the new social doctrines while her parents cling to the old—in such situations a break is inevitable—but even when the parents are also in sympathy with the new regime the Russian daughter has no longer the whole-souled devotion to them which she once had and which is still a familiar feature of family life in the rest of the civilized world. So much of her time is spent outside of the home, away from her parents, so intense is the influence of the larger society over her emotional and intellectual life, that her love for her parents cools as her fervor for the revolution mounts. In a conflict between loyalties to the one or the other, parents seldom win. I have yet to meet a revolutionary girl in Russia who, if it were required, would hesitate to sacrifice service to her parents for service to the revolution.

Yet in her attitude toward motherhood the Russian girl has changed but little. Odd as it may seem, the present regime exalts motherhood, and condemns as bourgeois decadence the present tendency of western women toward childlessness. Within the limits of its purse, the Soviet state encourages childbearing by a system of endowments that is unique among the nations of the world. For several weeks before and after childbirth, women working for the State are granted leave of absence on full pay; and no employer may turn down a woman applicant for a position in school or factory just because she is pregnant. All the medical expenses of childbirth, including hospital care, are borne by the State, which in addition grants a small allowance for each child born.

The State's beneficent attitude toward maternity tends to enhance the Russian woman's respect for it. Then, too, she sees no conflict between a career and motherhood. The two functions are easily combined, alike for the factory girl and the university graduate, by reason of the State's financial aid and the numerous day nurseries it provides. Nor does the fact that her child spends most of its early life in one of these nurseries mean that the mother is less fond of it. Visit any nursery, in city or village, in factory or school, during the hours when the mothers come to nurse their children, to take them home, or just to spend a little time playing with them, and you will be astonished at their outpouring affection for their offspring.

* Yet as the child grows up the bond of attachment weakens, in the child more readily than in the mother—a natural result of a system by which the chief responsibility for the rearing of children is lifted from the shoulders of the individual parents and taken over by society at large. It is too soon to say whether or not the Russian girl when she reaches middle age, when her children have grown up, broken home ties and gone away, will greatly miss their presence in her life. My guess is that she will, though not as intensely as did her mother and grandmother, whose whole lives were centered in those of their children. From her earliest days the new Russian girl is developing interests and aims outside of home life and family. When her children grow up and she is left alone she still will have her job or her social and political activities to fill her time and stimulate her imagination. It may be that the Soviet system of encouraging women to participate equally with men in the public affairs of the new society will eventually solve one of the most painful problems of our day—the fate of the domestically minded woman when her children no longer need her care and insist upon taking charge of their own lives.

Another departure from the old order in Russia is the modern woman's refusal to bear large families, since to do so would seriously hamper her participation in the activities of the new regime. Free dissemination of information on birth control and legalized abortion offer ber effective means of limiting her family to the number best suited for her purposes. As a resuit there has been a slight fall in the national birth-rate, which is bound to drop still further in the near future, since education in birth-control methods has but recently been accorded energetic attention. But while limitation of the size of the family is inevitable, aversion to childbearing is utterly foreign to the Russian girl, and as long as the present exaltation of motherhood continues there certainly will be no danger of race suicide.

(Continued on page 96)

(Continued from page 60)

It is in her relations with men, in her sex and love life, that the young Russian woman is experiencing her sharpest readjustment. Let me reiterate that from her earliest years she is educated to the idea that her main objective in this world is not a personal love life, but service to the revolution and to the new society which it is building up. Foreign observers, recognizing this objective, have concluded that the Russian revolutionaries deny the power and the need— indeed, even the very reality—of romantic love. Andre Maurois and Keyserling have bemoaned its collapse. Yet both are in error.

The outside visitor, especially if he is unacquainted with Old Russia, is likely to be of the same opinion, however. But this may mean simply that he has been misled by his impressions of the external scene in Russia. In his travels about the country he observes that the Russian girl is shabbily dressed. She seldom uses make-up, and when she does the result is often preposterous. Nor is she possessed of any of the mannerisms and affectations which to him are inseparable from femininity and from the ability to excite and experience romantic love. Her environment likewise seems to him as barren of sensuous stimulation as the very cobbles of the Moscow streets.

In the window displays of the leading shops, in the news and advertising columns of the press, in the theatres and motion pictures, he may look in vain for any suggestion of erotic feeling which might serve to stimulate her sex-consciousness. On the other hand, he sees her exposed to very powerful emotional excitement in which love has no part. In the schools and playgrounds, in the trade unions and factories, there are always campaigns in behalf of some new idea or new project, and forces are perpetually at work to arouse her enthusiasm for the new government and the policies which it is so strenuously promulgating. Naturally enough, he concludes either that the Russian girl is deficient in sex feeling, or that all her emotions of this nature have been sublimated into a purely social enthusiasm. Foreigners, especially Americans, have frequently asked me whether the Russian girl is really capable of emotional response. Such a question shows that the observer has failed to understand the Russian girl's background and training, and is judging her in terms of his own environment, in which sex is constantly emphasized in almost every phase of life and in the outward behavior of women themselves. Thus for him visible sex excitement becomes the basis of romantic love. This, of course, never was true in Russia, and is less so now than at any other time. The Russian girl may subordinate love to a social purpose; but that does not imply that she regards it as something unimportant or casual. This, at least, is her attitude today, notwithstanding the lurid pictures drawn in the recent crop of Russian sex novels which were based on the hectic life that marked the early days of the revolution, when everything was in a state of dissolution. Physically and emotionally Russia is becoming firmly stabilized, and the neurotic behavior of former times no longer holds true. The Russian girl of today takes her love seriously, as is the nature of the women of her country.

This is not to say that she is difficult of approach, for she plays about with men more freely perhaps than the girls of any other nation. But love is to her a precious emotion, not to be squandered lightly. When her love has been aroused, she responds with an intensity unrestrained by inhibitions and conventions, and the law of her land does not interfere with her love life. Marriage may not mean much to her, but love most assuredly does, as one quickly discovers when he comes to know any group of young Russians. Be they college students or factory hands, there will be found among them the same turmoil over love affairs that besets youth everywhere—indeed, perhaps even more, since in Russia everyone, especially the girl involved, takes these affairs so much more seriously.

Yet with all her emotional earnestness and all her freedom the Russian woman is far from enjoying an ideal, or even a satisfying, love life. A host of external conditions work against it in these days of revolutionary fervor and reconstruction. In most cities the housing is so wretched that families and newly mated couples are obliged to live in meagerly furnished one-room apartments. Food conditions also are difficult, and always, above all, there is work, work, work! When husband and wife are devoted revolutionaries, there are not many free evenings which they can spend together. Meetings and social work keep them out late into the night. The Soviet five-day week of four working days and one of rest makes no provision for universal rest days, and thus adds to the existing difficulties, for it means that often husband and wife cannot enjoy their rest on the same day. This may be a temporary condition, but while it lasts it is bound to be a disturbing feature in the love life of men and women.

Perhaps in the future if Russia fares well economically and attains a greater measure of social tranquillity, women will be able to enjoy an ideal love life. Certainly law and convention offer no interference, with divorce as easy and inexpensive to obtain as it now is. But at this stage of the revolution the obstacles are many and difficult to overcome. The fact that they may be only artificial and transitory does not make them less real and onerous for the present.

* Author of Humanity U prooted and Red Bread. See page 29 of this issue for a short biography.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now