Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNot to the swift

LOUIS GOLDING

In which the shades of Mr. Edgar Wallace lead a literary gentleman to betting on the horses

I went to the races today at Grünewald, which is just outside Berlin. Did I go in the special char-a-banc that takes you out for a few pfennigs? I did not. I went out in a hired limousine. Seeing that I could not by any possible chance lose on the six o'clock race was I the one to be niggardly about a limousine? I would never have forgiven myself for my meanness. Besides, little Helmut (let me call him that) was with me. It was Helmut who had put me on to Imperator in the six o'clock race. Could I possibly let him come out horse-racing with me in a mere taxi?

This article is partly a tale of little Helmut, partly a tale of my conscience. And Edgar Wallace has quite a lot to do with it, too. Little Helmut is little because he used to be a jockey. I didn't know that till yesterday. He and his wife live in the obscure tail-end of the apartment where I am now lodging in Berlin. I, being a literary gentleman, have a forward room that looks across the Spree through a lovely green tangle of tree-tops. I have a good view of the suicides which are attempted daily by the more disheartened Berliners, and which are sometimes frustrated.

I have often wondered when Helmut's turn would come. (I didn't know his name till yesterday, of course.) He seemed so forlorn and unnecessary, the way he wandered in at all hours of the day and night. His wife didn't look happy either. Who would, with Helmut for husband? (Do you know what that name means? Hell Mut—Bright Spirit! Very odd!)

Yesterday morning Helmut asked me for a cigarette. Not a mere match, mark you.

A cigarette. I felt pretty certain that that meant the opening up of pourparlers. I was right. I met him at the front door yesterday afternoon. He had doubtless been waiting for me a long time. He said "Shush!" and put his finger to his mouth. I looked behind me apprehensively. "Herr Professor," he whispered, "do you want to win a lot of money?"

What is the instinctive answer to that question? "Yes!" I said.

"Then, Herr Professor, may I come into your room and speak to you a few minutes?"

"Forgive!" I said. "I am no Herr Professor. Come this way! What is it all about?"

"Will you put fifty pounds, one thousand marks, on a horse that cannot lose?"

Fifty pounds!" I cried in terror. "There is no such sum of money! "

"Hush!" he bade me again. "Fifty pounds! What is fifty pounds to you? A literary gentleman! What would fifty pounds be to Herr Ed-garr Vall-ass?"

"I'm sorry," I said curtly. "I'm not interested in horse-racing. It's not my line!"

He looked shocked and incredulous. "But you are an Englishman! You come from sportland! You must not speak so!"

I tried to point out to him that sport and putting money on races are not interchangeable terms. Whereas I brandish my tennis racket with the next man, and have been known to kick the greasy football, I just did not put money on horses. Well, of course, an occasional shilling each way on the Derby favourite. . . .

"But Herr Ed-garr Vall-ass," he pointed out. "He owns race-horses. He too was once a jockey. But he made more money out of his books. So now he runs horses instead of riding them. Nicht wahr?"

* I tried to suggest that Herr Vall-ass and modern English literature are not synonyms. But, in company with some millions of Germans, he refused to believe it. Mr. Wallace is read in Germany a good deal more than Goethe, or, I should think, any German writer, dead or living. His long cigaretteholder protrudes elegantly from every book-shop window and book-stall in the country. "Es ' ist unmoglich von Edgar Wallace nicht gefesselt zu sein," reads the caption on millions of volumes. I don't remember the precise English wording. The German is much more seductively sinister.

That was how Helmut got me first. He made me feel that if I didn't fall in with his ideas, I would be unworthy of my craft, I would be letting Herr Vall-ass down.

"What do you know about horse-racing?" I said, trying to bluster a little.

"I? I am an ex-jockey!"

I have never met a jockey past or present. I was terribly thrilled, but tried not to show it. He had put a lot of weight on since his jockey days. But I could begin to understand now why he wandered about in that neglectedlooking way. "I tell you," he went on, "it is quite impossible for you to lose!"

I put on my most man-of-the-world manner. "Nonsense! What do you mean, quite impossible to lose?"

"Don't you understand, Herr Doktor? It's all arranged. Or it'll all be arranged in two hours. We know what horse is going to win! The others won't win! They'll not be allowed to!"

"What!" I cried. "You want me to mix myself up with a bit of dirty work? I'm sorry! You've come to the wrong shop! Well, I've got to get on with my work—"

"Herr Doktor," he implored. "I want you to understand. It is impossible for German racing to go on unless every third race is cooked like that. I am not speaking of the big events. It is the understood thing. It is not dishonest. It is the way that owners make their expenses. Do you know how much the upkeep of a horse costs these days? And the stables? And the trainers?" He reeled off an enormous list of figures. I have always been susceptible to figures. It did seem as if nobody could make ends meet unless a little money was made "on the side." (It will be recalled that this article does not pretend to expose German horse-racing. It is only a little tale of Helmut and me. And Mr. Wallace.) And was it my business, anyhow, the way the people behind the scenes managed these things? asked Helmut. He was giving me a tip ... a horse that couldn't lose. He wasn't asking me to sit on any horse and hold him from winning.

"What interest to you is it," I asked, "to give me an inside tip? I have the honour to live in the same house as you. Beyond that I don't know you."

"I'll be quite frank with you. My chance of earning a living comes when my own particular friends arrange a race like this. I ask for thirty per cent of the winnings." Then he added magnanimously:. "I only take thirty per cent after your original stakes are restored to you." Somehow that touch impressed me greatly with his bona-fides.

"What horse is it?" I asked.

"I cannot tell you," he said, "yet. I am going off to the lads shortly. Then we will decide."

"What race, then?"

"You will understand, Herr Doktor, I can say no word. Not until I have your fifty pounds in my hand."

"Fifty pounds!" I snorted. "How am I to know that your story is true—about all your jockeys sitting in counsel together?"

"Can I trust you?" He eyed me somberly.

"I am a literary gentleman!" I reminded him.

"Well, you can come down with me. We are meeting in the Zentral Hotel in the Friedrichstrasse one hour from now."

Suddenly a quite automatic spasm of nausea arose in me. My gorge rose at the whole shoddy business. "I'm sorry. I'm busy. I must really get down to it. Good-bye!"

Then Helmut played his trump card. He suddenly reached forward and seized my two hands. His eyes were moist with tears. "You have seen my wife?" he said. I said, "Yes." "You have not noticed?" "What?" I asked. "But she is ill, she is so ill!" "I am sorry!" I said briefly. "She has an illness on the kidneys, Herr Doktor. She needs another operation. The last one was a failure. I paid for it with my commissions on the last race with which my group of jockeys was tied up. I would back my last pfennig on them tomorrow. Her life depends on it. But I have no pfennig." His voice quivered.

(Continued on page 96)

(Continued from page 49)

The hard edges of my heart dripped like an icicle in a thaw. Had I the right to condemn the poor little woman to a premature grave? And her husband to an inconsolable widowerhood ?

I tried to make my voice as gruff as I could. "What odds?"

"I can promise you eight to one!"

"I'll put fifty marks on!"

"You will! You will! Fabclhaft!" His eyes shone. I realized I could easily have got away with five. But would his thirty per cent on five marks at eight to one pay for the operation? It would not. "I'll give you a receipt at once!"

"No!" I said. "We'll go down to the Zentral Hotel first. Then I'll make up my mind."

So we went down to the Friedrichstrasse.

"Listen!" he said. "You must come in a few minutes after me. We'll be in the Herrenzimmer. Sit down quite casually at a table near me!"

The thrill of all that was worth the money. What had Vall-ass in his myriad equestrian pages to compare with it? I followed him a few minutes later. Yes, there he was. There they all were —about nine jockeys and one exjockey. One of them had a face like Gerald du Maurier. I ordered a halfand-half and opened a Continental Daily Mail as if I were not a mysterious figure in a racing thriller. Oh, yes, they had their heads together. Helmut paid no more attention to me than if I were a table.

We met late that night. We arranged to leave for Griinewald next day.

"What is the name of the horse?" I whispered.

"No!" he said. "I'll tell you that when we set off tomorrow. I daren't breathe it tonight. If the lads heard about it—" he made the gesture as of a knife slitting a throat. "I understand!" I breathed.

He came into the house at twothirty on the day of the race. He was carrying a bottle wrapped in paper— probably medicine for his sick wife. I can't describe how that charmed me. It did more. It reassured me.

We set off at about four. The races began at three. But we people in the upper swim of horse-racing society don't turn up for the first race or two, like the mere rabble. It was a comfortable limousine, and fairly expensive. "What is the name of the horse?" I asked behind my hand, so that the chauffeur shouldn't hear.

"lrnperator!" he whispered.

"Ha!" I said.

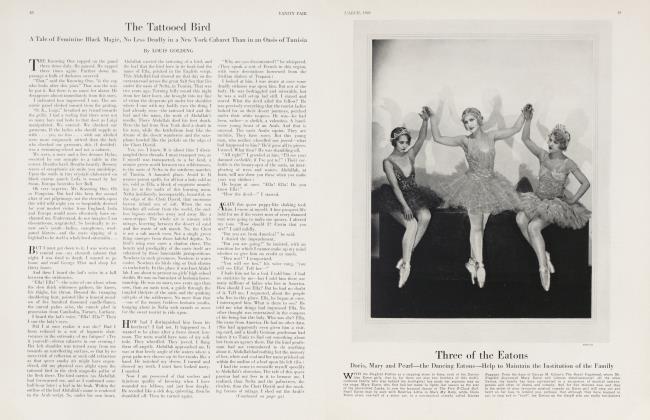

I found Griinewald to be one of the most beautiful race-courses in the world. The races were good races. I quite failed to make up my mind which were shtrate and which weren't. I suppose the jockeys have a lot of technique. But, frankly, I could hardly breathe till our race came on—my race, Helmut's race, Imperator's race. The six o'clock got under weigh.

"There, there!" Helmut muttered through his teeth. "That's him! Dark blue with a red cap!"

"Ha!" I said. My knees were knocking with excitement. The race started. I didn't know whether it was more intolerable to look or not to look. Imperator was running second. He was gaining! They were neck and neck. He was leading. My eyes could not stand it. They closed.

I opened my eyes. A totally new phenomenon had thrust itself forward. A fiend of a dappled grey was nosing forward, fast, faster. The jockey. . . . Was it? Yes it was! The jockey with a face like Gerald du Maurier. He was running a fierce second. He was gaining! He was gaining!

I looked at Helmut. He gabbled something in German. It was clearly the word for "double-crossed."

Imperator came in third, actually. Gerald du Maurier was an easy first.

"I am so sorry!" said Helmut, with a break in his voice. "I am so sorry, Herr Doktor! But listen!" He bent towards me. "We've got to get our own back. Now on Sunday, at Ruhleben—"

"Stop it!" I said unpleasantly.

My landlady tells me that Frau Helmut's kidneys are, so far as she knows, sound as a bell. But she drinks a great deal too much gin, she said.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now