Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE SCHOOL FOR PRESIDENTS

ALVA JOHNSTON

The New York public servant, when he peers out of his bedroom window in the morning, is surprised to find that he is not looking at the White House lawn. New York is now the national hatchery of presidential possibilities; every native-born Nordic on the public payroll from magistrate and bailiff to Senator and Governor dreams of entertaining the ambassadors in the Blue Room.

Any New York office-holder, who appears*in the public prints other than as a fugitive from justice, is immediately "mentioned for President" all over the country. If one of the sixty-five Aldermen makes a hot speech at the Lions' Club on a dull day, the A.P., U.P., Scripps-Howard, International, Universal and special correspondents flash it to forty or eighty million readers. That is enough to start the Alderman's boom and bring him in enough clippings to paper the walls of his speakeasy. The New York Governorship is the best of all stepping-stones to a presidential nomination. New Yorkers are all plotting to work their way up to the Little White House at Albany, and from there it is an easy jump to the big one on the Potomac. A1 Smith, a former subpoena server, nearly made it; the field is obviously open to all.

The White House dominates New York politics. The state legislature is an arena for making and breaking presidential candidates. Every item of the state's business is tainted with national politics. Bills to mend footbridges and regulate the open season for muskrat are fearfully inspected to find the presidential angle. For eight years the sole objective of the New York Republican legislators was to hurt A1 Smith's chances for the presidency; for the past three years their main aim has been to hurt Roosevelt.

The White House menace has strange effects on New York public men. It makes them self-conscious. They are always in training for directing the national destinies. They learn to hesitate and vacillate over the simplest matter; can't decide whether to strike out with the left foot or the right foot in entering a room; talk too much or are afraid to talk at all. Alienists say that New Yorkers lead the world in the habit of muttering to themselves, and it is probably because so many are rehearsing their inaugural addresses. Office-holders react wildly when they feel their presidential potentialities squirming inside of them. New York police-court jurists hand down thirty-page decisions quoting Coke, Grotius and the Justinian code. The chief official of one of the local subdivisions of New York, on being mentioned for the Presidency, set out on a private goodwill tour of South America and traded views with South American presidents on how to run republics. Jimmie Walker still holds up his hand in faintly negative gestures at shouts of "Jimmie for President." Franklin D. Roosevelt spent nearly thirty years perfecting that papier mache smile; while Owen D. Young peppers the world with his counsel and stands ready, if necessary, according to a witness before a U. S. Senate Committee, to furnish advice to nursing mothers.

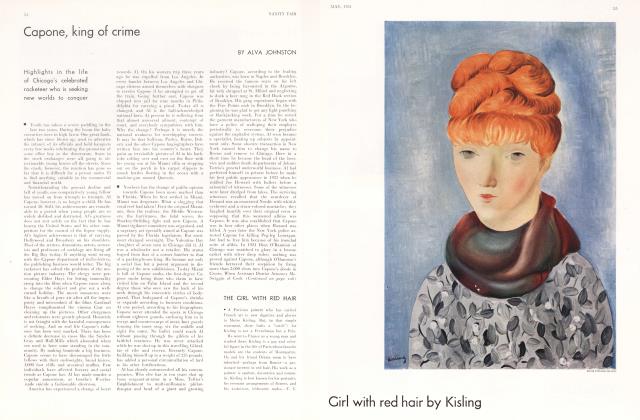

The Governor of New York, though often cheated out of his birthright, is the American Grown Prince. Former Governors of New York were candidates in nine of the last sixteen elections—Seymour in '68, Tilden in '76, Cleveland in '84, '88 and '92, Roosevelt in '04 and '12, Hughes in T6 and Smith in '28. New York Mayors are of the blood royal. Seth Low and McClellan were "mentioned" abundantly a generation ago. Colonel House was planning a boom for Mayor Gaynor but switched to Woodrow Wilson. Squads of Warwicks from the South and West visited New York to inspect Hylan. Walker would be a dangerous contender to-day if the country had confidence in a statesman with a wasp waist and parabolically curved coat pockets. A New York quill-driver, Horace Greeley, and a New York judge, Alton B. Parker, have been among the Democratic standard-bearers. Investigators of New York scandals—Tilden, Hughes and Seabury—always cast their shadows on the White House. But the true Prince of Wales is the Governor. Even a man so obscure as Dix, accidentally elected Governor in 1910, was immediately placed at the head of the list of Next Presidents. Sulzer, who succeeded Dix, had his head so turned by his presidential boom that he made the ruinous error of trying to be a good Governor, whereat he was impeached and thrown out of office by Tammany. Charles S. Whitman was as good as elected, but outmaneuvered himself by championing the dry cause in New York. Former Governor A1 Smith is the dean of presidential possibilities, and his successor, Roosevelt, is already receiving applications for his Cabinet.

There are several reasons for New York's pre-eminence as a school for candidates. Politicians naturally take a deep interest in New York because of its ninety electoral votes. Then the New York official can always shine before the country; he has his choice of slaying the saber-toothed Tammany tiger or the upstate Republican dragon. The chief cause, however, of the teeming pre-presidential life in the Empire State is that New York is the news, radio, rotogravure, newsreel, gossip column, magazine and publishing house headquarters of the United States. A Pennsylvania or Illinois politician has to be caught buying a million votes to get national attention; a New York politician can get it by rendering an opinion on a prize-fight; he can have a worldwide newsreel circulation by awarding medals to the champion rat-catcher and ashcan-roller; he can reach the rotogravure public of the world by going to church in a silk hat or eating a hot dog in a bathing suit. Mayor Walker hit the front pages of the nation by the simple policy of slipping in the bathtub and dislocating his shoulder. The New York official, merely because he is a New York official, is introduced to the folks around the country by McIntyre, Winchell and Brisbane; Skolsky, Kitchen and Hellinger. He speaks on nationwide hook-ups. His wife, if she photographs well, can help along the propaganda by endorsing mattresses and corn-plasters. Simply because -he is so handy to the cameras, microphones and news services, the New Yorker has an enormous advantage. Politically, the nation has got itself all snarled up in the leased wires of New York. Washington is an important news centre, but the Washington news does not elect presidents; it tells what is wrong with them after they are elected.

The career of United States Senator Royal S. Copeland illustrates the short-cuts to fame open to a go-getter in New York. Copeland, a middle-aged, middlewestern Republican, removed to Manhattan Island, got to be Health Commissioner because of his great honest eyes, started a column of health hints in the Hearst papers and became a United States Senator. To-day he is a veteran presidential possibility because of his legion of readers who in ten years have learned how to doctor themselves for 3,650 diseases. The present Health Commissioner of New York has a column of his own and is getting the White House manner.

New York not only raises candidates for its own use, but is able to restock other regions from its surplus. It shipped the veteran Manhattanite, William Gibbs McAdoo, out West where he was domesticated overnight and palmed off on three Democratic conventions as a Californian. From its glut of candidates in 1924, New York culled the Wall Street lawyer John W. Davis and presented him to West Virginia. New York is now having a poor year. It has practically no unhatched Republican candidates. Ten years of double-dealing and fraud on the dry issue has demoralized New York State Republicanism, hut under its new management it may be relied on to have a fine selection to present in the near future.

(Continued on page 92)

(Continued from page 33)

New York threatens to have a complete presidential monopoly some day. It now has more White House prospects than any three or four other states, and the only reason that it does not furnish all the leading candidates is because New York is nearly as busy destroying candidates as creating them. Ohio, mother of third-rate presidents, seemed to be losing its grip.

The New York public schools graduate thousands of scrubby young White House possibilities every year. Most of them are speedily destroyed by their natural enemies, but hundreds survive to middle and old age. In New York the courtesy title of "Our Next President" is as common as "Squire" in our rural districts or as "Prince" in the husband-producing regions of the Caucasus. There are three approaches to the White House. One is by strength of character and positive accomplishment which compel the politicians and press to fall behind the man of action. This is the best method, but the hardest; it was the method of . Theodore Roosevelt, Charles Evans Hughes and A1 Smith. The second is that of currying favor with the politicians; a good example is that of the New York City executive who, to oblige a political boss, appointed fifteen lifeguards who couldn't swim. The third method is that of cultivating the newspapers, a method never more thoroughly exploited than by the late Coroner Julius Harburger. Julius furnished the press with sensations every day by the simple method of declaring all suicides and accidental deaths to be mysterious murders of the circulationboosting type. So far as he could help it, Julius would have no natural death; he regarded it as cheating the fourth estate. "It's a murder" was the slogan of this friend of journalism. Hauled out of bed to be asked if he was going to run for Sheriff, Julius sleepily exclaimed, "It's a murder."

The most subtle combination of the three recipes for becoming President was achieved by Franklin D. Roosevelt a year ago in his "public officerspublic acts" letter. About thirty Tammany office-holders had been invited to tell the grand jury what they knew about the purchase or sale of judgeships. The Tammany men draped the Constitution about themselves and stood mute. Roosevelt would have been destroyed politically if he failed to make some gesture of good citizenship. He wrote a letter to Mayor Walker demanding that "public officers" testify about their "public acts." It all sounded as truculent, forthright and downright as Theodore Roosevelt or Grover Cleveland. But the grand jury was not seeking information about the "public acts" of these men; it was seeking information about their private acts; the peddling of a judgeship being, technically, a private act. The real effect of the Roosevelt letter was to show the Tammany boys how they could gracefully avoid testifying. Thus in one phrase Roosevelt came to the rescue of the distressed ermine merchants and made himself a hero with the press and public. None but a man who had spent twenty years in the New York state school for the Presidency could have won the hearts of the moral forces of the community and of the immoral forces of the community with the same sentence.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now