Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFloor-Show

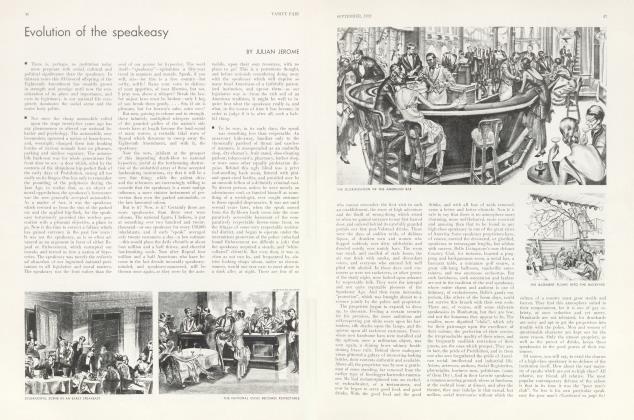

JULIAN JEROME

Foujita, the famous Japanese Parisian artist, illustrates some seductive moments seen in the New York night-clubs

There is no better way—as any Cook's tourist will tell you—to form the picture of a city's superficial cultural standards than to make a tour of its midnight haunts of amusement. The London Supper-Clubs, the boites de nuit of Paris, and the Viennese and Berlin nacht-lokale mirror these standards in colourful, if not always accurate forms that every year are faithfully reported by scores of visitors to Europe.

But it is a remarkable fact, that while many an American has been known to travel far, to travel wide, and often very low, in his efforts to capture, in a foreign metropolis, this revealing cosmopolitan "atmosphere", when the same man is apprised of its existence in his own town, or, more particularly, in New York City, he is prone to view it with a certain insular snobbery, as something either very dull, or very vulgar. So that while he speaks of a Montmartre cafe, or a Kurfiirstendamm Kabarett, with an almost philosophical ecstasy, he grows impatient, or faint with disgust at the mention of a Broadway night-club.

It remained for aliens to our shores (with perhaps the local aid of a Carl Van Vechten) to disclose to him the picturesque savageries of Harlem, and the gilded barbarities of Broadway.

Of course, it is also true that just at the moment in American civilization when we were most ready to express our national temperament in Night-Clubs, a bastard brood of Speakeasies, sired by the 18th Amendment, sprang up, a mushroom growth, flourishing,

(as mushrooms do) in the darkness and dampness of a thousand little side-street areaways and cellars. And it was this illegitimate offspring of the night-club, the saloon, the beergarden and the cabaret which drew, not only the patronage of the American public, but the attention of those scriveners who presume to find in the speakeasy the perfect expression of American midnight morals.

It is precisely here that the scribblers err, for it is not the bar-and-brass-rail which epitomizes the fundamental yearnings of the urban pleasure seekers, but the Floor-Show, and the antics performed each night in that small polished space in front of the nightclub's orchestra, which really reflect a city's prejudices, vanities, perversities and desires. If anyone should doubt this, let him consider how all the more successful speakeasies are adding to the waning lure of the Bar per se the essential attractions of the night-clubs: dancers, orchestras, crooners, singers—in short, Floor-Shows.

But avoiding the formidable array of 35,000 speakeasies, an owl's-eye view of New York City would still reveal a flourishing number of night-clubs which, in their different colours and aspects, reflect like so many facets of a sombre gem or—if you prefer—a paste diamond, the hard, glittering surfaces of the Manhattan Mind.

Beginning at the top of the night-club strata, the visitor would find himself in that little paradise of the middle Social-Register, the Embassy Club. Here, in a setting which borrows its inspiration from the London Embassy Club, one finds that the patrons, themselves, with the egotism typical of all more or less aristocratic milieus, prefer to be their own Floor-Show. Every night, between eleven and two o'clock in the morning, a hundred or so welldressed, slightly subdued couples twirl somewhat solemnly around a comfortably crowded floor, to the strains of Pancho's nicely modulated orchestra. It is seldom that one espies an unfamiliar face, or a familiar frock, and either occasions a little agitated whispering among the ladies, who derive their great pleasure, in thus presenting themselves, night after night, to their oldest friends in their newest gowns. This soignee, mildly perfumed atmosphere of husbands and wives and guests who are being "paid off" for previous invitations, is perhaps, a trifle dull. But its value lies in this,—that the Floor-Show here does most definitely sum up the highest ideal of the haut bourgeois of America: which is, as it has always been, something essentially respectable and thinly British....

(Continued on page 86)

(Continued from page 68)

The gayer "smart young things" whose inherent respectability is susceptible of certain rosy rifts, take themselves to the El Patio Club, where the dancing is better, where the lights are lower, and the air a little less pure, but where all the tables on the floor are still diplomatically given over by Mario, the shrewd captain, to people that "one knows". ... El Patio, the Club Richman (a little more robust—a little less "chic"), Montmartre, The Lido, those Half-way Houses of the emotions, frequented by debutantes of two seasons ago (and facing many more) by the glad-hand boys—struggling "customers' men"; by middle aged women with little humps on the backs of their necks, thrown into prominence by the enormous diamond clasps of their pearls; by women who want to go to bed, but are afraid to; by young, pretty women in Vionnet and Patou gowns who smoke incessantly; by baldish, yawning, prosperous-looking men in well-cut dinner coats with slightly wilted collars; and men of an indeterminate age with a faintly foreign aspect, sporting occasional monocles which lend them a dubious distinction; by swarthy-hued Levantines, accompanied by satinsheathed, bleached blondes (but, where are the diamond bracelets of yesteryear?) . . . The night-club tides them all over their Zero Hours, which come between twelve and two o'clock, when to be alone with themselves, and to face the futilities to which city lives are always heir would be too cruel. They are bored, restless, insatiable, but satiated, and here they seek what here only they can hope to find—and night after night, reject: an erotic, rosytinted vacuum, in which they may, with one hand cling to the linseywoolsey skirts of respectability (that eternal ideal of the bourgeois) and with the other timidly pat the silken knee of Pleasure. . . .

Perhaps the most authentic offering to the Manhattan flesh-pots is Broadway's Hollywood "Restaurant."

There is in evidence here, as in all successful night-clubs from Harlem to the Battery, a sprinkling of ermine coats and boiled-shirts, but the crowd is composed mainly of that motley of Broadwayites whose means of livelihood are so difficult to determine, of shop-gentry, bootleggers, suburbanites on a spree, Riverside-Drivers, chorus girls out of jobs, and, one fondly imagines, magistrates and judges, who if they are not, ought to be missing.

The Hollywood Club is perhaps the spirit of Broadway, it is a vital spark struck from a piece of brass.

Then there is Jean Malin's "smart" Club Abbey, where through a lavender mist, a somewhat bewildered clientele smirk with self-conscious sophistication at the delicate antics of their host. With good natured tolerance, Mai in provides a Floor-Show that is less clinical than the wilted postures and tense warbling of himself and his confreres, Helen Morgan, Jr. and a crepe paper costumed confrere. There are girls, bona fide and young, and they too, do the Rumba . . . but like native coin in an alien land, here the Rumba seems to have lost its value. The Club Abbey, The Club Calais . . . there must be others, too. They are the growing pains of our metropolitan culture.

Harlem completes the night-club cycle that began with the Embassy Club's pallid elegances, took on colour at the El Patio, blushed with robust vulgarity at the Hollywood, and paled at the Abbey's polite aberrations. (Greenwich Village, with its pseudoartistic, and naive perversities lies to the South, lending a young and sophistical glimmer to the night-club aura of Manhattan.) But Harlem, with its animal humours, its thick-lipped laughter, its high-lights on ebony, is the mammy of the night-world, nursing at her black breast the jaded appetites of Social Registerites and Broadwayites alike. . . . Connie's Inn, The Cotton Club, (to name the more synthetic and elaborate of Harlem's haunts) The Spider Web, The Lenox Club,—on the stairways of all of them there is a faint (and sometimes not so faint) odor which one associates with jungles . . . and with zoos. ... In Harlem, life grows suddenly simple, for all mysteries are concentrated in the one great mystery: the mystery of the flesh. One's body is one's God and the music of Duke Ellington's orchestra knows this: its rhythms are tuned to the beat of the blood, even as the African tomtoms are. Snake Hips, well named, dances at The Cotton Club, and the prolonged, incredible undulations of his body become at last more symbolical than suggestive. Here in Harlem, the visitor fancies he touches, with white, manicured fingers, life that is raw, vigorous, a little brutal. Brutality thrills the languid ladies from Park Avenue pleasantly. With the natural masochism of those who have never tasted their birthright of pain, they feel refreshed and purged by emotions which are impulsive, simple and savage. . . .

So Harlem's Floor-Shows add their primeval beat to the sound and fury which probably signify something in the night clubs of New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now