Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

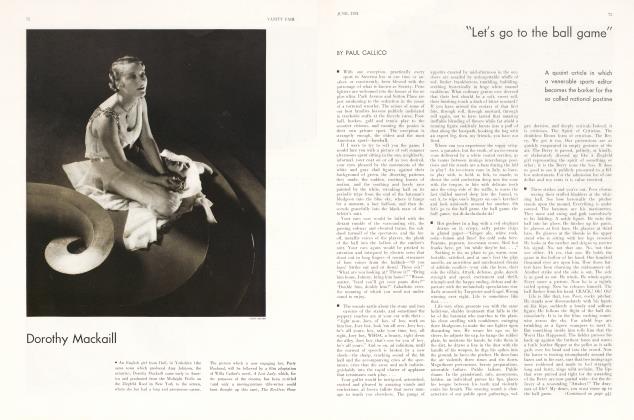

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe girl who danced with the Prince of Wales

JULIAN JEROME

A fable about one of the favourite dancing partners of the Heir to the English Throne

■ The scene was an American city, and the ball was in honour of the visiting Prince of Wales. It was a splendid affair, and the girl, sitting in a corner chatting amiably, even romantically, with a personable young man, was delighted to have been included among the guests, particularly as she was aware that she was the unimportant daughter of an unimportant father. But she was modestly satisfied that her frock was pretty and her appearance charming, and while she told the young man gaily that he was "much handsomer than the Prince," she happily imagined herself the next day describing to her less fortunate friends how the Prince looked at close range, and with which of the beautiful and important ladies he had danced.

It was at this moment, half of reverie, half of idle, pleasant banter, that she saw moving towards her the equerry to the Prince of Wales. He paused beside her, bowed, smiled.

"His Highness," he said in quite an ordinary, unemotional voice, "would like to have the pleasure of the next dance with you." He extended his arm. The nice young man— with whom she had felt she might easily fall in love—discreetly vanished.

She gazed at the equerry with wide, startled eyes. Suddenly the world in which, up to that moment, she had lived, seemed to drop away from her like Cinderella's rags. She was going to dance with the Prince of Wales! She rose, a little unsteadily, to her feet.

As she walked back to the ballroom on the equerry's arm, she was dazed. Afterwards, she recalled that she had said a few words about how surprised she had been, and wondered if she had giggled or had said something silly.

She had the presence of mind to curtsey three times to Edward Albert Christian George Andre Patrick David Windsor, Prince of Wales. The next minute she was gliding smoothly and somewhat slowly around the crowded floor, on which she and the silent Prince somehow always seemed to whirl in a little vacuum.

"I am encircled," she thought, "by the arms of the Heir to the British Empire." And although she looked neither to the right nor to the left over the thin black shoulder of His Royal Highness, she knew that everyone was looking at her, the women with envious, glittering eyes, the men with eyes that seemed to see her for the first time.

■ Her heart beat furiously.

"This is like a fairy story," she reflected, "and I am indeed Cinderella, and he is Prince Charming. Oh, if only . . ." Her breast became suddenly clogged with an emotion so strong that she felt certain she would faint. Her hand, in the Prince's impersonal grasp, trembled. She was still whirling round and round. "All the King's horses, and all the King's men," absurdly went through her head.

But the feeling which agitated her was one of neither sentiment nor vanity. It was, indeed, more akin to religious ecstasy. Jove had descended from Olympus to sit at the feet of a shepherd girl . . . Paris had given to her the golden apple . . . She had felt the wingbeats of an Angel of the Lord . . . All the dreams and fantasies of her childhood, the stories of crowns and sceptres, the glittering and wishful visions of young princes and golden-haired princesses, the long and magnificent, great and gloomy history of England, the pomp and circumstance, the ermine and velvet of tradition, the privilege of the Purple, the crimson flush of power . . . were crystallized for this little American daughter of democracy into her own intimate possession, and for a moment she, too, felt the apartness of royalty, as she danced with the Prince of Wales.

The music ended. Bowing and smiling vaguely, the Prince murmured a few polite words, which she could hardly hear, and left her in the care of his equerry.

It is barely possible that the exaltation of those fifteen minutes would have been no more than a bright and beautiful dream, if Edward P., harassed but gallant, had not said to an insistent reporter the following day, "Miss .... was the prettiest and most charming girl I have met in your country."

She had been the obscure and modest daughter of an obscure father. After this royal accolade she became Front Page News. The Prince went on to other countries, but her photographs continued to appear in newspapers all over the world as "Wales' Favourite Dancing Partner." Overnight she became a social leader in her city. She was interviewed, courted, flattered, envied, imitated in word and gesture. She was asked to write articles on Ballroom Deportment, organize charities, star in pageants (usually as Britannia), and endorse cold creams. Insatiate for further glories, she moved on to the capital. Her triumphal progress was heralded by an avid press. She was reported engaged to this prominent young man or that wealthy old one, but either she or her father (who had by this time assumed the role of personal manager to the Anointed) haughtily denied these plebeian rumours.

She grew a trifle sad, wistful and discontented, in the manner of those who have once trod the asphodel fields and must henceforth spurn the asphalt pavements. . . .

All this was four or five years ago. Since then the Prince has had many other Favourite Partners. Their momentary glory, which is the reflection, bitter though blinding, of his kindly humour and his princely gallantry, has long since eclipsed her own. She is now about to marry a real-estate agent in her home town (to which she has long since returned), because—although this she would not admit— he is the only man who has dared ask her in several years, and she is getting on. . . .

At her wedding she plans to wear, according to her own story, which she telephoned to an apathetic assistant society editor, "the dress in which the Prince first saw and admired me. . . ."

When some curious or insensitive person asks her what Edward said to her while they danced, she closes her eyes, and answers in a voice pregnant with mystery and heartbreak, "Do not ask me. The subject is sacred."

She believes this. She will force her husband to believe it, and her children, and possibly her grandchildren. And when she is old, she will still, in thwarted moments, refer in a plaintive voice to "the time I danced with the Prince of Wales."

And, she will be considered by everybody (including her children and possibly her grandchildren) as a terrible bore.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now