Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHigh spots at Carnoustie

BERNARD DARWIN

How Armour won, and the deep tragedy of the losers, MacDonald Smith, Jurado, Percy Alliss and Sarazen

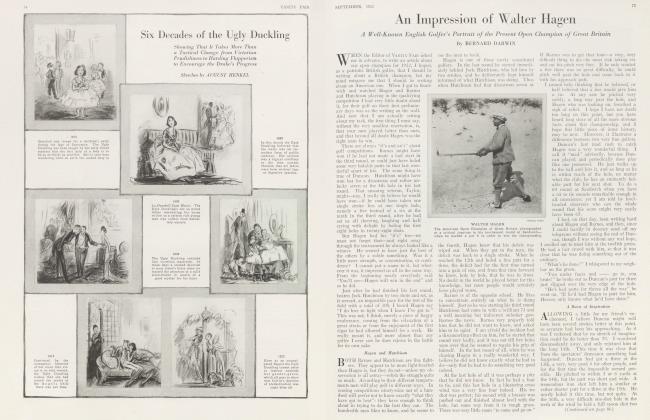

The most obvious fact about the British Open Championship at Carnoustie was that Tommy Armour won with a score of 296, coming up from behind with a grand 71 in the last lap, and that poor little Jose Jurado, from the Argentine, faltered on the very threshold of victory, took six instead of four at the last hole but one, and was beaten by a single stroke.

The whole championship was what the Duke of Wellington called the battle of Waterloo, "a d-d close-run thing," and that being so, all those who almost won—who were so near and yet so far—must have spent bitter hours of recollection in cursing themselves for some two or three shots thrown away. The memories of those shots must have beset their pillows like little black, malignant imps and said "Come, wake up, my fine fellow. Don't think we are going to let you sleep in peace. Don't you remember me? I am the shot you put into the bunker when any sensible man would have played short. I am the stupid little two-foot putt you missed when any old woman could have knocked the ball in with the handle of her umbrella. I am not going to let you forget me. But for me you would have gained immortal honour and glory, not to mention goodness knows how many dollars. Now is the time to toss and turn in remorse and wonder how you came to be so foolish."

If Armour had just lost instead of just winning this championship he would have lain awake thinking of two or three—nay, more than that, four or five—tiny putts that he could have knocked in one-handed with the back of his iron. His driving was magnificent; his iron play was worthy of what he is, the best iron player in the world; his approach putts were hit as sweetly and cleanly as need be, but the short ones only remained not tragic because, in the end, they did not matter. And then there was Gene Sarazen, sturdiest of all small heroes. He would have won, I think, if the weather had been kinder to him; he had the worst of the wind for each of the first two days and though one cannot estimate the loss in any precise number of strokes, it was beyond doubt considerable. That will not worry him for, as he philosophically said to me, "You must have the breaks to win a thing like this." But just two strokes, lost unnecessarily and at one fell swoop, never to be recovered, may keep him awake. I came up with him at the seventh hole in the first round and when he holed his putt in four, he had done those seven holes flawlessly in twenty-eight. He had his three at the short eighth and wanted a four for 35 to the turn—a splendid start.

There was a wood on his left but he had plenty of room on the right—"acres and acres of grass" as Sandy Herd once said reproachfully to James Braid who had hooked him into a bunker in a big foursome. And then Gene, lashing out with too exuberant confidence and giving his natural hook too much license, saw the ball sail away out of bounds into that wood of black and ominous firs. Stroke and distance penalty; there were two strokes clean gone, never to be recalled, and he lost to Armour by two strokes in the end.

There was Johnnie Farrell, too. Just one hole may be said to have hung a millstone round his neck which he could never unloose. He had begun with 72. His second round had started sufficiently steadily till he came to the long sixth hole, some 520 yards in length. He had two fine wooden club shots and was quite near the green with a clear road to the flag. He could have run the ball along the ground; he could even have putted it, but, as he said to me, "We generally pitch, in America," and he pitched too strongly, ran over into the bunker and took three putts. That was seven instead of a likely four, an easy five. He played with indomitable courage home against the wind, but the three strokes were gone and he finished three behind Tommy Armour.

As to Jurado—well, there was that seventeenth hole which he can never possibly forget. "I'm sorry for the wee man," said my neighbour in the crowd and that was the universal sentiment. No one felt more acutely than his patron and pupil, the Prince of Wales, who had made a night's journey to see the last day's golf and followed Jurado most eagerly. Even now I hardly know how it happened. He discreetly took a No. 3 iron from the tee, lest, with the wind behind he should reach a distant stream, and, by one of golf's little ironies, he put the ball into another bend of the same stream almost in front of his nose. And so I might go on with examples to all eternity, and so it always will be in golf; the two or three strokes that would never have been wasted by a fat old gentleman with a caricature of a swing, have a way of wrecking the greatest golfers in the world.

I suppose it is really ridiculous to use the word "tragedy" in connection with a game. "After all," says Mr. Common-Sense, who is no golfer, or who plays for fun and exercise, "it is only a game and there is nothing, criminal in missing the ball. You are spoiling; the game by taking it too seriously." All that is perfectly true, but it is of no comfort to the man who. wants to win a championship more than anything on earth; all championships seem to me rather tragic and cruel things, even though the losers put smiling masks on their faces, and this was one of the crudest of all. I am sure it was a tragedy for .MacDonald Smith, who was making the supreme effort of a lifetime. Here were all the elements of romance and tragedy combined. He was a born Scot coming back to play on his native heath of Carnoustie in its first championship. He was no longer very young, his chances were growing fewer with the years; he had been so very near so very often; he had settled down on the edge of the links a long time beforehand, had lived laborious days of practice and scorned all other prizes, greater in superficial value but as nothing compared with this one. He had trained himself to the hour and all Carnoustie hearts were with him and now—supposing; he should fail! His first round began dreadfully; he was, after six holes, on the verge of utter failure and by resolute courage and a machine-like power of going on hitting he redeemed himself and finished in 75, three shots behind the leaders but well within range. His second round was neither good nor bad, 77, and now he was five strokes behind, with half his course run and a big spurt was imperatively needed. The big spurt came; he had a grand 71 in the third round and headed all the field, save Jurado who still led by three; and Jurado, was playing as if nothing could go seriously amiss. At worst he must surely make a tie of it. And then, at the supreme crisis, suddenly and surprisingly, he broke and took 5, 6, 5. It was all over. I saw that six—four strokes to hole out, from twenty yards from the flag, with never the ghost of a bunker in the way—and, upon my word, I felt like some ghoul who had deliberately gone out of his way to see a poor trembling wretch in his last moments on the scaffold. I never felt sorrier for any man in my life.

(Continued on page 78)

(Continued from page 62)

Tommy Armour's victory was not only the victory of a very great golfer but one of stern resolution over nerves.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now