Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMen of steel

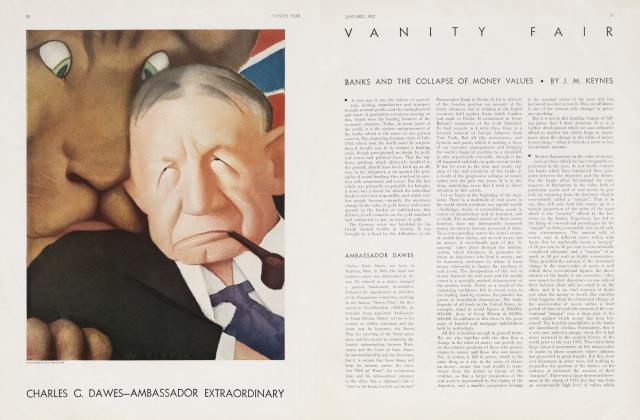

ALEXANDER NAZAROFF

Wherein the thick veil is torn from the private lives of the Soviet leaders, and in particular Joseph Stalin

Upon his arrival in Moscow, a foreigner visiting Russia may receive an invitation to a dinner or a tea at the Reception House of the Commissariat for Foreign Affairs. No other country has an equivalent of this institution. It is a place where the Soviet Government acts in person as a polite host; it is here that it entertains foreigners, especially important ones, establishes personal contact with them and, so to speak, displays before them that "face of the Soviet regime" which it wants them to see.

A huge and heterogeneous crowd, including all specimens of humankind from international business men and the eternally traveling old American ladies to the members of the French Parliament and Turkish and Polish diplomats, gathers here on such occasions. Among the hosts, one sees some of the most interesting Soviet figures. Here is the little, fat Maxim Litvinov, Russia's Commissar for Foreign Affairs; and here are Mrs. Litvinov, his wife, A. Lunacharsky, the ex-Commissar of Education and many others.

The House itself, with its flights of reception rooms whose immaculate parquet floors reflect valuable old paintings and ikons, porcelain, gilt and excellent furniture, is palatial (formerly, it was the home of a great Russian sugar king). The food served on silver plates by well-drilled lackeys is regal —from caviar, delicious salads and masterpieces of the French kitchen to a century old cognacs and wines (Romanoffs had excellent cellars which still last), everything is exquisite here. ... On this old regime background, the shabby day suits (no evening clothes are to be seen here), loud voices and plebeian manners of the hosts, Russia's present rulers, form an original and symbolic contrast. Their very figures seem to say to the guests: "You come from the bourgeois world, and we are ready to treat you to luxury; but look at us and remember that this is a proletarian republic!"

In the hub-bub of laughter and merry voices, the guests drink, eat, converse. Litvinov, the official master of the House, sits beside an American lady. With his little, restless eyes drowned in the fat of a round face, his pince-nez on a ribbon which render his arrogant countenance pompous, and his short, plump hands, he reminds one of a petty dealer from a South Russian market place. But no one would now perceive in him the usual impertinence of his diplomatic notes. He is politeness itself. The American lady sums up the outpouring of her first impression of Russia with the words: "Of course, you will understand, I am not a Bolshevik; but I feel that it is such a daring and wonderful experiment!" He smiles understandingly. She is charmed. Indeed, how could he help smiling: he remembers very well the time when this "wonderful experiment" formula was coined in Moscow as an advertising slogan for the Soviets, for use in America. ... A Frenchman makes some teasing remarks on the "new morals" of Russia to Madame A. Kollontay, the famous Soviet Ambassadress to Stockholm. This is not an indifferent subject to her: the Ambassadress, who is no longer very young, but who still tries to keep young and dresses remarkably well for a Soviet lady, is known to have championed— both theoretically and practically—the cause of the "free proletarian love" so zealously that even the late Lenin, who was a hardboiled man, was scandalized and publicly upbraided her. . . . Far from minding her interlocutor's sarcasm, she wittily ripostes something about the strictness of Parisian morals. She, generally speaking, is witty, sharptongued, intelligent. And thus, oiled by old wines, conversations grow more and more informal, intimate and friendly.

Among the hosts, there is one who, by his immaculate costume, formal manners and official reserve, sharply differs from his democratic colleagues. No wonder; the name of this young man is N. Florinsky. The offspring of an aristocratic family whose father, a general, had been shot by the Bolsheviks, he was not only spared by them, but even invited to serve as the Chef du Protocol (Master of Ceremonies) in the Commissariat for Foreign Affairs (the new rulers did need a man like this; for in those days some of them literally did not know how to hold a fork). . . . Thus, like these old paintings, parquet floors and wines, he is a fragment of the past which has survived the upheaval. What does he think while comparing this gathering with the grand style of the formal events of the Imperial regime (for then, too, he was in the diplomatic service)? He won't tell—his reserve is proverbial in Moscow.

The guests leave, delighted by the hospitality, broad-mindedness and warmth of their hosts. They have seen, however, the "reception-face" of Soviet rulers. Their serious, business-like countenance is different.

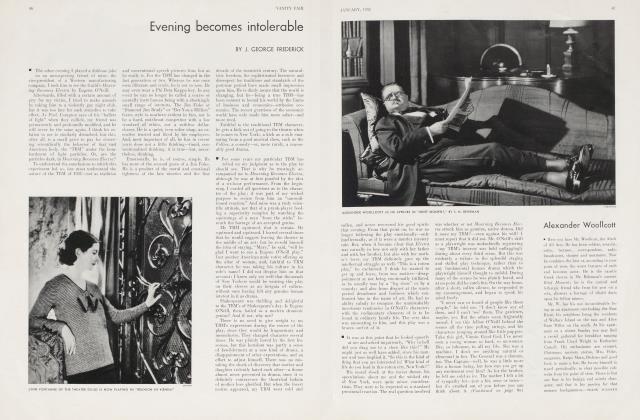

Every morning, at eight, a middle-aged, dark-eyed Caucasian wearing high boots and a military hakki coat emerges from a house in Gorki (a suburb of Moscow), dives into a sedan where armed body guards await him and speeds to Moscow. His sedan is preceded and followed by open touring cars occupied by agents of O.G.P.U. (Soviet Secret Police). The road and the house from which he has emerged also are heavily guarded. It is thus that Russia's Dictator begins his day. For the dark-eyed Caucasian is Joseph Stalin.

Who knows? Perhaps, while thus driving, he sometimes remembers other days—the days when, a redoubtable "fighting Bolshevik", he himself attacked, with a bomb or a pistol in hand, the corteges like the one in which he now is driving. For Stalin's career is amazing. Not only that this most powerful single ruler of our days, who reigns autocratically over 160,000,000 human beings and one-sixth of the territory of our planet, was born in the poor hut of a cobbler; which is still more striking, he began his climb to power as a highroad bandit.

After the Russian revolution of 1905 was crushed, Lenin understood that, in order to continue the struggle against the Czardom, he needed funds. But the Bolshevist treasury was empty. Yet the famous Bolshevist leader never hesitated: he ordered his party to raise cash by armed hold-ups.

It was then that an obscure member of the Caucasian Bolshevist organization, Djugashvili by name (for such is Stalin's real name), sprang into limelight. Hitherto, this young Asiatic (for he is a Georgian by birth), repulsively unclean, uncultured and secretive, frowning and spitting fire at the slightest provocation, was unpopular even with his fellow revolutionists. But soon he won the deep respect of the whole party. He proved that there were two things in him: absolute fearlessness and iron will-power.

He organized the Bolshevist "fighting squad" and became its leader. In the years from 1906 to 1908, he soaked himself in blood as deeply as few men ever have been soaked. With the quickness of lightning, his squad raided the stores of wealthy Armenians; on picturesque, mountainous high-roads, he attacked mail coaches had sacked the travelers, etc. But the masterpiece of Stalin's fearlessness which dumbfounded the whole Russia was the famous "expropriation of Tiflis" in June, 1907.

(Continued on page 70)

(Continued from page 29)

On that morning, two carriages, surrounded by a convoy of mounted Cossacks, started from the State Bank to the Treasury of that city; they were transporting 340,000 roubles received for administrative needs from St. Petersburg. As the cortege was nearing the Palace of the Viceroy of the Caucasus, several bombs were whirled at it and terrific explosions shook the air. The street was plunged into chaos: the smoke, shattered windows, the groaning, bleeding bodies of Cossacks, horses and passers-by—all mixed. Meanwhile, some men were firing revolver shots at the surviving guards; and a man disguised as an officer snatched something from the debris of one of the carriages and galloped away in a cab ...

Stalin received the bombs for the "Tiflis Affair" from Lenin, who then was hiding in Finland. The money thus "earned" he conveyed to Paris. There, it was converted into French francs and safely transmitted to the Bolshevist Central Committee by one M. Wallach, a revolutionary who, after his flight from Russia, lived in London engaging in petty—and often shady —speculations. At the present time, this Wallach, known to the world as Maxim Litvinov, is that very Soviet Minister for Foreign Affairs whom we saw politely entertaining foreigners at the Reception House.

Soviet historians no longer dissimulate these facts. Why should they? True, we of the "bourgeois" world are not accustomed to statesmen with such "political record". But, according to the new morals of Moscow, the throwing of bombs is a virtue, and not a crime, if these bombs tear the flesh of the "class enemies of the proletariat". "All that is moral which contributes to the victory of the revolution."

Let it be added that Stalin was four times arrested for minor revolutionary crimes (the police never knew that it was he who engineered these hold-ups) and exiled to Siberia; and four times in succession he fled from Siberia. Indeed, daily risking his life, he struggled and wriggled out of the hands of his enemies but always came back to strike again.

Now, Stalin's black hair is considerably grizzled by advancing age and overwork. His simple, but neat khaki clothes fit well his muscular, soldierly frame. He is very taciturn and reserved; he speaks little; "No man will ever know what the Master has on his mind"—they say of him in the Kremlin. But he listens with great attention; and his hot Caucasian eyes smile shrewdly, with calm self-assurance, piercing and scrutinizing the interlocutor. In this poised and composed man, who would identify the former bandit?

The private lives of Communistic rulers are enshrouded in a thick veil of secrecy. The fact remains nevertheless that, having miraculously risen to power, some of them display a great greed for the "joys of life".

Unlike his comrades, Stalin has no vices. He neither gambles, nor runs after women. He dropped his old wife and took a young one (being a busy man, he performed all the formalities by mail). But ever since he has had the reputation of a loving and faithful, although despotic, husband. Moreover, his high boots and military clothes are no decoration; his tastes are extremely simple; in his Gorki house, he lives with the modesty of the well-to-do, but sturdy and economical farmer. Finally, money does not interest him in the least. He has just one passion—an insatiable, unconquerable thirst for power.

In the bitter struggle for the place vacated eight years ago by Lenin's death, he overthrew all of his rivals, from Leo Trotzky, the famous Red War Lord, to Kamenev, Zinoviev and Rykov. The cold-blooded, Asiatic perfidiousness, the insight into human nature and the genius for invisible political manœuvering which he displayed during this struggle are equalled only by his fearlessness of the Caucasian days.

Today, he is victorious. Officially speaking, he is but a "modest" Secretary General of the Communist Party. But, from his two modest rooms in the Kremlin, he holds the Communist Party in his iron grip as tight as he held his "fighting squad" in the Caucasus; and through the Party he controls the Soviet Government and the entire Russia. Coming to him with official reports, the Commissars tremble: "The Master" never loses his selfcontrol ; but he can be extremely brutal. Besides, through the Secret Police, he knows literally everything that is being done and thought by his subordinates. And those who are guilty before him know that he never forgives an offender. It is thus that he rules. He often has been compared with the Czars. This comparison hardly is accurate. Inasfar as his methods are concerned, he rather reminds one of Al Capone, or of medieval Asiatic bandit rulers.

Is Stalin a sincere Communist? No doubt, he is. He has hated the "capitalistic world" since childhood; in this he is a fanatic of Communism. But Communism is to him that which he wants and approves of; and he sincerely believes that every offense against his person is an offense against Communism. "L'Etat c'est moi"—in these words he might, with perhaps a better reason than any other ruler, sum up his whole political philosophy.

His shrewd eyes look with deep contempt at the foreigners so hospitably entertained in the Reception House. To him, foreign business men who do business with Soviet Russia are "traitors to the capitalistic class"; and, according to the French proverb, "Treason is appreciated; traitors are despised". According to his former secretary, G. Bazhanov, he sincerely believes that the World Revolution will come; why shouldn't it? In his opinion, the "broad minded" capitalists are zealously helping his cause. Meanwhile, he smiles and waits.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now