Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Theatre

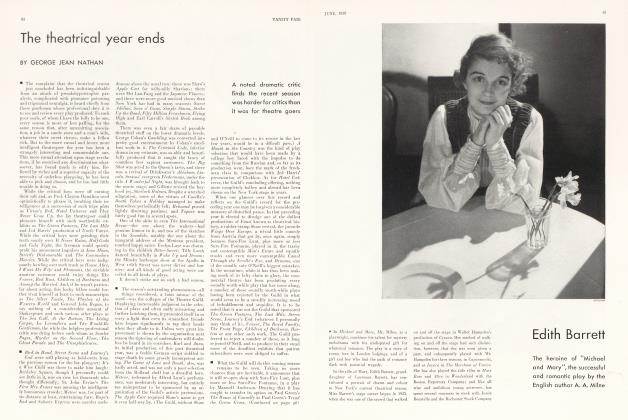

George Jean Nathan

OUR PREMIER DRAMATIST.—While waiting for the loftily disparaging English reviews of Eugene O'Neill's Mourning Becomes Electra which, following the arbitrary deprecation of almost everything American, will in all probability be coming along as soon as the published version of the play reaches the British critics, let us, in the new light of this, his latest work, consider O'Neill's position among present-day English-speaking dramatists. That he is the most, in fact, the only important serious dramatist that this country can presently offer needs no restatement for Americans. But that, with the possible exception of Sean O'Casey, Great Britain can at the moment among its immediately active writers for the theatre offer no serious playwright his equal is a postulate that may call for some explication in behalf of both nations.

The erstwhile important serious older writers for the English stage have gone to pot in recent years. Shaw's later work has been merely a feeble rehash of familiar materials; nothing that he has produced lately has come within hailing distance of his earlier efforts; he gives every sign of being played out, though—like some prinked and still hopeful elderly gallant in tete-a-tete with a piquant maiden—he still goes through the various superficially realistic motions. Galsworthy's The Roof, recently presented here, provides a melancholy example of that once estimable dramatist's collapse. His plays have steadily become weaker and weaker, the fizzing of so many soda-pop bottles mistaking themselves for philosophical Bollinger. Pinero disappeared from the scene a decade and more ago with The Thunderbolt; his work since then has been utterly negligible. Among the younger men, Granville Barker, in the opinion of this critic, was never much better than a pretentious second-rater. St. John Ervine, after achieving a highly merited reputation with several very excellent examples of the serious drama, has in later years devoted himself exclusively to light comedy and so volitionally removes himself fromthe catalogue with which we are immediately concerned. In the way of light comedy, incidentally, Great Britain offers a half dozen writers greatly superior to any that we can offer—Ervine, Ashley Dukes, Lennox Robinson and Maugham among them. No American has written a comedy of the quality of Dukes' The Man with a Load of Mischief, or Maugham's The Circle, or Robinson's The Whiteheaded Boy, to name but three. About the nearest that American comedy has come to the wholly reputable in recent years is Behrman's The Second Man and the Kaufman-Ferber collaboration, The Royal Family, although on two occasions Vincent Lawrence and on one occasion Elmer Rice have come a foot or so within striking distance. In farce, parenthetically, it is a different story; the English have produced nothing in late years in the same class with the best American farces during the same period.

To return to the so-called serious dramatists and omitting the two British exponents of the purely poetic drama, Stephen Phillips and John Masefield, neither of whom has figured conspicuously or fortunately in the drama of the last ten years, and regrettably as well being forced to eliminate Dunsany and Yeats on the score of their inactivity—the latter's meagerly poetic The Cat and the Moon certainly doesn't provide critical counter-evidence —we find no one else in Britain at the present time writing serious drama of any consequence. Only O'Casey, whose The Plough and the Stars—to single out his best play—is one of the superbly fine things in modern drama, remains a figure of real importance. And it is thus, O'Casey alone excepted, that O'Neill at the moment looms head and shoulders above all the other serious dramatists of the two English-speaking nations. In the last half dozen years England has offered only O'Casey's work to compare with O'Neill's, and aside from the O'Casey masterpiece mentioned it has produced nothing to compare with Strange Interlude or, now, Mourning Becomes Electra.

While presenting O'Neill in this encomiastic light, it must not be imagined, however, that one sees him as a compendium of all the virtues, a fellow purged of all sin, his head encircled with a critical halo and his nose magnificent with a brass ring. He has his faults as he has, very much more richly, his virtues. Of both, though of the latter more especially, Mourning Becomes Electra is an illuminating mirror. It once again discloses its author as the most imaginatively courageous, the most independently exploratory and the most ambitious and resourceful dramatist in the present-day Anglo-American theatre. It once again gives evidence of his contempt for the theatre that surrounds him and of his conversion of that contempt into drama that makes most other contemporaneous drama look puny in comparison. It dismisses the little emotions of little people in favor of emotions as deep, as profound and as ageless as time. It opens the windows of the stage, so habitually shut against the world of pity and comprehension and terror, to that world again. But, so heroic is its intention, its sweep and its size, that its characters, like the characters in certain other plays by the same author, are themselves not always up to the sweep and size of their author's emotional equipment and emotional philosophy. In other words, it sometimes happens that it is O'Neill, the dramatist, rather than his characters and quite apart from them, who agitates and moves an audience. In other words still, the characters that O'Neill creates are at times the after-images rather than the direct images and funnels of his overpowering and unbounded emotional imagination. They are periodically too inconsiderable to contain him. They sometimes give one the impression that the load he has placed on their shoulders is too heavy for them to carry. They present themselves occasionally in the light of characters valiant, faithful and obedient, yet not equal to the demands their creator has made of them. Thus, though Mourning Becomes Electra is indubitably one of the finest plays that the American theatre has known, its Greek emotions now and again embarrass the American characters into which the author, loosing the flood-gates of his copious emotional fancy, has projected them.

In the modern drama to which we are accustomed, the emotions of the characters are often more trivial than those of the members of the audience. It is a rare play nowadays that imposes anything more than the most superficial of emotional demands upon an audience. For it must be remembered that the theatre audience of today is a different audience from that of other years. It is, in considerable part, the intelligent, experienced and sophisticated residuum of the erstwhile heterogeneous mass of theatregoers that embraced the present happily expatriated movie, talkie, radio and other such elements. Its elected and most prosperous dramatic fare is no longer such stuff as Strongheart and The Lion and the Mouse but Strange Interlude and The Barretts of Wimpole Street. The larger number of dramatic exhibits offered to this new audience by the commercial producers fail to satisfy it. It is a platitude that intellectuality has little more to do with drama than with music, poetry or home-brewing and that, as with these other arts, it is largely a question of emotion or nothing. And the emotional content of forty-nine out of every fifty present-day plays is approximately that of a clam juice cocktail. As a consequence, they fail to stir an audience in the slightest degree, for the audience, as has been observed, is usually just about twice as dramatic and twice as emotionally competent as the plays. The average man and woman in the selected theatre audience of today have in their own lives, and consequently in their own theatrical imaginations, emotional resources considerably superior to those of the usual play characters that they waste three dollars to watch. They are thus not even vouchsafed the pleasure of enjoying a vicarious emotional experience, for the dramatic emotions which they attend are largely those of emotional fledglings and so are not only insufficient to provide them with any reaction but are, to boot, pretty often unintentionally humorous. It is no wonder, under the circumstances, that the intelligent theatre-goer presently patronizes music shows in preference to drama and that, when anything at all possible in the way of open and shut farce comes along, he gallops to it for the dose of Katharsis denied him in the serious theatre.

(Continued on page 74)

(Continued from page 24)

Into this theatre and into this audience, starved for an emotional purge, O'Neill has come with the physic that both have longed for. Into a theatre that night after night has dribbled out the meagre little emotions of ladies' maids dressed as grand ladies, Cockney actors listed in programs as builders of empire and men and women generally with passions as persuasively incendiary as warmed gumdrops, he has brought, since almost first he began to write, a new full heat and madness and fire. The little faint flickers of dramatic flame that now and then lap pathetically at the edges of the Anglo-American stage have been stirred by him into something more like a conflagration, whose glow has reached even beyond that stage to the stages of Scandinavia, Russia and Germany.

In Mourning Becomes Electra, an independent reworking in terms of modern characters and the modern psychology of the Greek Orestes-Electra legend of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides (which has seemingly created a terrific demand among the critical gentry for Schlegel's brief, convenient and labor-saving synopses of the Greek classics), O'Neill has once again taken over the present-day theatre and made it his own. From five in the afternoon until close to midnight he harrows and mauls, taunts and tortures, prostrates and exalts his characters, set into the New England scene at the close of the Civil War, with the lash and the blaze of his passionate inspiration. I: is this inspiration, mad and crimson and mighty, that transcends his characters and play and that, like the glow of a steel furnace against the heavens, impresses the vision, the feeling and the fancy even though the furnace itself be a mile away. The characters are metaphorically this furnace, sometimes remote, not always immediately actual and not always plausibly determinable —the affinity between the psychology of the son of Agamemnon and the son of a New England Yankee soldier, for example, is not always altogether convincing; but the glow, spreading over all, luminous and radiant and dazzling, is the glow that is O'Neill.

A parenthetical observation in conclusion. To superficial critics of O'Neill's writing career, the trilogy idea is associated specifically with his more recent development. A study of his canon, however, reveals the fact that, from his earliest beginnings, his dramatic mind, if not always his actual dramaturgy, worked with and toward that idea. The trilogy impulse is readily to be detected in three of his short plays of the sea, published under the general title of The Moon of the Caribbees. Beyond the Horizon, as he himself now sees it in retrospect, was essentially a trilogy arbitrarily compressed within a single, regulationlength play. Dynamo, as is well-known, was the first play of a trilogy the writing of which he abandoned. Strange Interlude, as he originally visualized it and as he outlined it to his friends years before he set himself to its execution, was a super-trilogy. There is even a hint of the trilogy sequence in the nature of the emotional philosophy and its development in the recurrent battle of the sexes and Mother Earth theme in certain of his other plays. The dramaturgical form that the volcanic emotionalism of Mourning Becomes Electra takes is thus simply a natural outgrowth of a seed that has been in his work since first he began to write.

THE MELANCHOLY DANE.—After seeing what Mr. Norman-Bel Geddes did to him, no wonder he was melancholy. This Mr. Geddes, who is undoubtedly one of the most Teutonicly impressive scenic designers in the American theatre, not long ago produced in our midst something that was nominated in the advertisements, and even in the programs handed out to the audiences, as Hamlet. But while at intervals there was a vague resemblance to the Hamlet, that Shakespeare wrote and while now and then there seemed to be something faintly familiar about the proceedings, what Mr. Geddes for the most part put on the stage was simply Mr. Geddes. And when momentarily modesty seized him and he allowed Shakespeare for a minute or two to interfere with his own self-glorification, poor Shakespeare suggested nothing so much as educated Cecil B. De Mille.

While I am surely not one mustily to believe that an intelligent producer cannot take a certain liberty with Shakespeare, I still am of the mind that there may well be some discrimination between liberty and a Communistic souse. Mr. Geddes did not merely take liberties with Hamlet, he went in for everything from free speech to the corruption of the morals of minors and from wholesale deportations to arbitrary censorship. He deprived the Ghost of his right of speech and gave his lines to Hamlet; he caused the King, while in the Queen's company, lasciviously to rub his hand up and down the leg of a young girl standing next to the throne; he banished Fortinbras, Osric, Voltimand, Reynaldo and Cornelius from the text; he didn't like the more familiar of the two soliloquies and sought to drown it in the wings; he converted Polonius to Judaism; he turned Ophelia, despite the beautiful performance of Miss Celia Johnson, into a Helen Morgan who substituted the stage apron for a piano; he apparently considered Shakespeare a not very competent dramatist and so omitted the preparation for one or two important scenes, notably that of the foils; he cut the text to the melodramatic skeleton and got rid of most of its poetry; he pulled the curtain before Horatio had an opportunity to speak "Not from his mouth, had it the ability of life to thank you"; he edited a number of Shakespeare's phrases; he did just about everything to Hamlet, in point of fact, but bring on Moran and Mack in the players scene and have Hamlet die on Christmas Eve in a snowstorm. And as I reviewed the exhibit on the opening night and as Mr. Geddes is nothing if not an inventive and courageous fellow, he may, for all I know, have done even that sometime later on in the week.

Mr. Geddes is an uncommonly talented designer of stage sets and costumes and he is also a proficient hand at stage illumination. That should be sufficient to assuage his vanity. As a director and producer of classic drama, he is impudent, incompetent and juvenile. The sooner he persuades himself to stick to his last, and a gleaming and proficient last it is, the better it will be for him and for a drama that he may then serve as auspiciously as he now makes mock of it. His Hamlet, botched in general casting, in treatment and in all save scenic effect, his Hamlet externally begauded with thousands of dollars worth of arclights, spotlights, searchlights, floodlights, radium-lights, borderlights and funnel-lights and with enough scenery to enter into competition with the Grand Canyon, his Hamlet in silks and velvets and satins, his Hamlet with its elaborate Berliner stage processions and groupings—this Earl Carroll Hamlet of his isn't onehundredth so effective, true and moving as the three or four hundred dollar production in street clothes that Basil Sydney put on just around the corner a few years ago.

TWO TALENTS.—In the aspersion cast earlier in this treatise upon American comedy writing, I entered an exception in the cases, among others, of the MM. Rice and Behrman. Both of these men stand out conspicuously from the generality of Americans in their field. Both have potential gifts —now and again gifts already realized —that provide considerable hope for the future. In these pages last month, I told you of the former's The Left Bank, as sharp and truthful a piece of comedy writing as has come into the American theatre in some time and one that falls short only on the score of periodic over-insistence and undue emphasis. Rice's newest work is Counsellor-at-Law, which, while not nearly so competent a performance as the earlier play, yet reveals him again as the most shrewdly observant recorder of character detail writing at the moment for our comedy stage. The complete truth of his character drawing remains impressive even when the temptation to thrust it into slightly grease-paint situations periodically overcomes him. Once he rids himself of this temptation—you will find a striking example of it in the last five minutes of his latest play—he will, unless all signs fail, prove to be a comedy playwright of definite position. As he stands today, he is the most authentic writer of purely native comedy that the American stage has offered since the days of George Ade, though their work itself is as far apart as the poles.

Behrman's talents, which reached their flower in The Second Man and which subsequently showed themselves but fitfully in the comedy called Meteor, is most lately represented by Brief Moment. In no way up to the quality of The Second Man, it still gives evidence of character wisdom, of writing felicity and of a grade of humor that for the most part has nothing in common with the obvious. Its defects lie in a tendency arbitrarily to relieve every slightly serious situation or passage of dialogue with a laugh and the occasional passing off of a somewhat egregious polysyllabic utterance for literary composition. In spite of these faults, however, a general intelligence, comprehension and wit inhere to the play, as to the antecedent two by the same author. Above Behrman's other virtues is the happy faculty of finding exactly the right word for the right place. What is more, he accomplishes the finding without the so often subsequent audience impression of self-consciousness and labor. His right word pretty usually has the proper casual ring.

While I have often freely employed the word truth in connection with dramatic writing and, in the last two months with Mr. Rice's writing in particular, it should, of course, always be remembered that I use the word in a patently relative sense. The drama at its truest always inevitably remains little more than a convincing prevarication. Its remoteness from actuality and life is of such degree, indeed, that the mere inclusion in it of so much as the name of a real, living person always comes as something just a little bit startling to an audience.

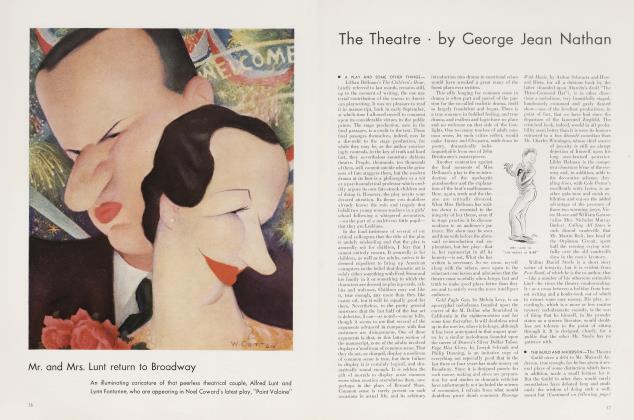

ADDENDA.—Robert E. Sherwood's Reunion in Vienna is largely a matter of Lunts and is therefore often more entertaining than it might otherwise be. Nevertheless, Lunts or no Lunts, the manuscript is an improvement over the antecedent ones by the same author. It contains several episodes amusing on their own account and a somewhat better grade of humor than that divulged in Mr. Sherwood's previous exhibits. The comedy dawdles too much at the outset—the first act is given over to more preparation than a middle-aged bride on her nuptial night—but once it hits its stride, it provides very fair theatrical pastime.

Cynara, by the Messrs. Harwood and Gore-Brown, enjoys the virtue of reticence. By taking a commonplace theme—a husband's casual infidelity and its lack of any true bearing upon his love for his wife—and by refraining from allowing its essential banality ever to get into the actual spoken word, the authors have succeeded in implying to their audiences a subtlety and originality that are not critically evident. Several scenes in the play, notably those between the husband and his inamorata, are nicely handled with what may be described as a literary silent moving picture technique. Several others, when open-andshut dialogue triumphs over the authors' trick of reserve, are merely the obvious stuff of the showshop. A very good, company has been hired to merchant the manuscript.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now