Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

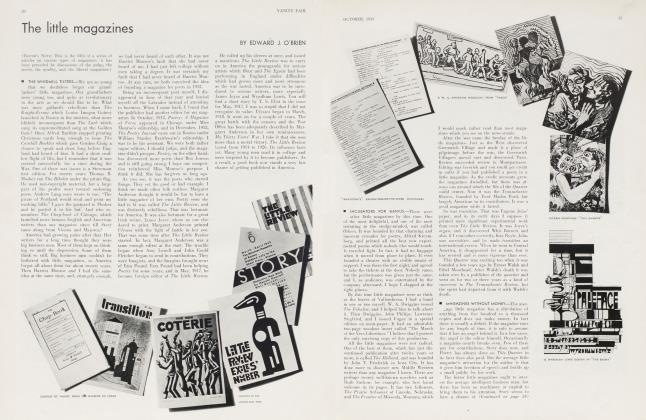

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEugene O'Neill—strong man of American drama

GEORGE JEAN NATHAN

A best friend but not the severest critic of a famous dramatist denies the imputation of favoritism

■ Since my early critical interest, many years ago. in his work, there has persisted a legend that my close friendship with and personal affection for him have induced in me a critical astigmatism as to his defects as a dramatist. The legend is gifted with such blood-pressure, indeed, that so recently as four months ago another friend of his, in the flow of a discourse that agitated the tall palms outside his library window on that island off the Georgia coast, delivered himself of the opinion that my constant and unremitting endorsement of O'Neill had done him more harm than good, inasmuch as it had in all likelihood—for such is sometimes the peculiar critical reaction—prejudiced other commentators against him. Upon the friend's oracularity, O'Neill himself ventured nothing, merely—as is his wont when a view on almost any subject is desired or expected of him—contenting himself in slowly dredging himself up from the depths of his chair, moving at snail's pace to a distant cigarette box. laboriously extracting therefrom a cigarette, and consuming at least three minutes in the lighting of it and meditating the flavor of his initial puff.

His fair wife, Carlotta, however, let out a whoop. "Endorsement!" she fulminated. "Constant endorsement!" she went on. "What do you mean? Did you read his unspeakable reviews of Dynamo? I hadn't met him then, but I said to myself, 'Anyone who could he that nasty and unfair to Gene, dismissing a whole play in terms of a mere lengthy cataloguing of exaggerated stage directions, would never be allowed within even hailing distance of me!' Then what of the unholy ridicule he poured on Welded, and what of his abrupt dismissal of The First Man? What, too, of his criticism of Lazarus Laughed? Why. the fellow even found fault with one or two things about Mourning Becomes Electro, which even the critics most hostile to Gene praised whole-heartedly!"

■ I take the impolite liberty of quoting Mrs. O'Neill's denunciation of my occasional critical attitude toward her husband because it constitutes a much politer exculpation of a professional critic than any such critic might, within the precise bounds of professional taste, vouchsafe to himself.

One of the irritations that beset the critic is the common imputation to him of motives of one sort or another. It is generally believed, for example, that the critic cannot be the friend of a man and yet view him and his work impersonally. The closer the friendship, the more—so goes the conviction—is it likely that the critic will he drawn toward arbitrary praise. It is assumed, in other words, that not only is the critic himself a half-wit but that he is in the invariable habit of picking out only half-wits for intimate friends. That friendship may follow, rather than precede, work ably and soundly done, that it may be based upon mutual respect and a regard for personal integrity and honor, and that any invasion or corruption of any one of these would immediately end it. is apparently overlooked. O'Neill probably does not relish my periodic dispraise of his dramatic writings any more than I in turn relish his periodic impatience with and dispraise of my critical writings, hut that does not interfere with a decent friendship.

■ I have been reading his plays in advance manuscript form for, now, something like fourteen years and. sometimes, long before they have seen the light of theatrical performance. have expressed my favorable or un-favorable opinion of them to him. He has sulked on occasion, has even called me a damned fool, when we have differed, hut it has meant no more to him than it has to me when, for instance, upon reading the advance manuscript of one of my recent books, he has expressed a very decidedly un-favorable opinion of it and I. in turn, have called him a damned fool. We are, I suppose, friends for better or worse, till the water-wagon or continued had work in the case of either of us doth us part, and that—disturbing as it may he to some—is that.

When I started to confect this little piece on him, I had an inclination to give it the title, "The New O'Neill." I refrained for the reason that, though the O'Neill of today is a considerably changed man from the O'Neill I have known in past years, no man ever really changes so greatly as to warrant any such absurd politico-journalistic caption. Yet that there has been a change in the old O'Neill is unmistakable.

When I first knew him, back in the earlier nineteen hundreds, O'Neill—or Gladstone (his middle name) as it is my facetious custom personally to address him—exuded all the gay warmth of an Arctic winter. To say that he was a melancholy, even a morbid, fellow is to put it mildly. Life to him in those days—and not only life but his stock-taking of his own soul—was indistinguishable from a serial story consisting entirely of bites from mad dogs, fatal cancers and undertakers disappointed in love. His look suggested a man who was just about to guzzle a vase of C33, H45, No12, and his conversation suggested a man who had guzzled it. In addition, he was chronically so nervous and physically so restive that he generally gave one the impression, what with his constant sharp, jerky glances to the left and right, that he was imminently on the worried look-out for the police. When he took hold of a highball glass, his hand shook so that he sounded like a Swiss hell ringer. In the last four years he has regained a calm and tranquillity of such proportions that their very adagissimo almost induces in one all the nervousness and restiveness that used to he his. Nothing am longer disturbs or remotely agitates hint. He is at peace with himself and with the world.

One of the greatest recent changes that has come over him. however, is a recapture of the humor that was in hint in those distant days before even he began to write, in the days that I have described in the volume called The Intimate Notebooks of George Jean Nathan, when, at the dives known as Jimmy the Priest's and the Hell Hole, where he made his residence, lie was part and parcel of such low buffoonery as has seldom been chronicled in the biography of homo literarum Americanos. That this humor will be evident in certain of his coming plays. I think I may safely predict. There was a long period when humor and the O'Neill drama were strangers the period when he himself was in the spiritual, mental and physical dumps although even then, despite the seeming skepticism of his critics, there were occasional fleeting symptoms of that grim humor which was in him in the old. previous days and which was struggling pathetically and often baffled to come again to the surface. But the new O'Neill humor is not a grim humor; it is a kindly and gentle and often very tender humor, wholly unlike any that has fitfully edged its way into even those of his plays that have not been abruptly catalogued bv his critics as "morbid", "gloomy", "lugubrious", or what not. Ah Wilderness, which the stage will see this season, will testify to the fact.

B As one of his critics. I have never been one, incidentally, to be persuaded that O'Neill's drama is exactly what the majority of his commentators have professed to regard it. to wit, a drama uniformly bereft of any and all traces of humor. There have been plays, of course, as noted, that have been and properly—as devoid of humor as Bach's passacaglio in C minor or a toothache, hut there assuredly have been others that have contained some very genuine humor, whatever qualifying adjective doubtful critics may elect to attach to it. Marco Millions is fundamentally and in the aggregate a humorous play; Desire Under the Elms has plain shots of sardonic humor; the beginning of The Emperor Jones is tickled with a humorous straw: there is open-and-shut humor in some of the early sea one-acters; and there are glints of humor here and there in other scripts. To argue that O'Neill has not had humor because a lot of it has been of the grim variety is to argue, on the same ground, that neither had Ambrose Bierce any.

Another change in O'Neill—and one that will be detected in Days Without End. which is to be produced, along with Ah Wilderness. in the near future—is a mood of optimism and faith that has supplanted his old, indurated pessimism and disillusion. Where formerly his outlook on life and on himself was glum and bitter, there is in him now evidence of a measure of philosophical rosiness and pious trust. As his personal life has been eased with solicitude and affection and faith, his mind, once cramped and clouded, has perceptibly mellowed and brightened. He is not yet a gay fellow by any means, for it is not in his horn nature to be gay, but compared with his previous self he is a veritable rhapsody. Life and the world and the agonies of humanity are still, of course, a source of much brow-wrinkling for him, and not a little meditative pain, but back of it all one can vaguely hear a tune singing in his heart. Speaking of tunes, by the way. his present greatest desire is to install in his house one of those old-time saloon-bordello pianos that were operated by dropping a nickel into them and whose façades, immediately the nickel was deposited, burst into a magnificent illumination. Such a proud musical instrument he has succeeded, after six months' assiduous search, in locating. But there is, alas, a hitch. It is impossible, it seems, any longer to get hold of the barroom records that, to the delight of all connoisseurs of the good, the true and the beautiful, it used to play.

(Continued on page 54)

(Continued from page 31)

O'Neill is the hardest worker that I have ever known, and, in the roster of my writing acquaintances, I have known a number of pretty hard workers. There isn't a minute of his working day that his thoughts are not in some way or another on his work. Even when sound asleep, Carlotta informs me, he will once in a while grunt and be heard to mumble something about Greek masks, Freudian psychology or Philip Moeller. A few months ago, swimming with him after two hours in what seemed to me to be waters still at least sixty dreadful miles from the safe Georgia shore, and with both our stomachs full of wet salt, he turned over on his back for a moment, ejected a good part of the Atlantic Ocean from his mouth and told me that he had just been thinking it over and had decided to change one of the lines in his second act. I have eaten, drunk, walked, motored, bicycled, slept, bathed. shaved, edited, run. worked, played. even sung with Vim. and it has been a rare occasion, take my word for it, that he has not interrupted whatever we were doing to venture this or that observation on this or that manuscript he was then busied upon. He may be reading the morning newspaper, or studying the Washington financial letter service to which he subscribes, or lying half-asleep on the beach, or fishing for pompano, or gobbling a great bowl of chop suey, or hugging his wife, or openly envying some newfangled sport shirt you may happen to be wearing, or making a wry face over Dreiser's poetry, or doing anything else under God's sun, but you may be sure that what he is thinking about all the time and turning over in his mind is something concerned with his work.

A dozen times a day he will stop in the middle of a sentence and, without a word of apology or explanation, depart, head dejected, to his writing room to make note of a line or an idea that has just occurred to him. lie has, at the present moment, note-books full of enough dramatic themes, dialogue and what not to fill all the theatres in New York for the next twenty years, with sufficient material left over to fill most of those in London, Paris and Stockholm. I not long ago asked him about two or three rather fully developed ideas for plays that he had told me of a few years before at Le Plessis, in France, where he was then living. "Oh, I don't think I'll ever do anything about them." he allowed. "I've got a couple of dozen or so new ones I begin to like better."

O'Neill's chief professional concern in more recent years has been the problem of casting his plays to his own satisfaction. The dearth of good actors, principally in the male department, causes him no end of anxiety. So much, indeed, that not long ago he confided to me that his ambition, once he gets enough money to be safe, is not to permit his future plays to be produced hut simply to publish them, uncorrupted by careless and obfuscating acting, in book form. "You can say what you want to about the theatre back in my old man's time," he held forth, "you can laugh at all those tin-pot plays and all that, but, by God, you've got to admit that the old man and all the rest of those old boys were actors!"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now