Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLydia and the ring-doves

KAY BOYLE

• The laurel tree grew up to the window, and in the spring its white flowers opened, not quite, but edging on to fullness, and it blossomed with reserve. In the month of April they were scattered all over the tree's brow like a milky veil.

The other ornaments it wore were the ring-doves who came there to mourn. "Ah, God, ah, God!" they sobbed aloud in the branches. They peered through their bright relentless eyes for sustenance and fluttered the black lace of feathers on their throbbing throats. "Ah, God, ah, God!" they murmured of the frugalness of England, and laid their heads sideways to hark for Lydia opening her window.

Lydia gave them bread on the eaves and tried to stroke them. In all the strange country, they in their grieving had come closest to her heart. The bit of the sill with the rain or the sun lying on it, and the rosy eyes of the birds upturned to her were the simplest things she had found in England. Everything else there had a name and a form, a rooted life that set any being of the new world outside.

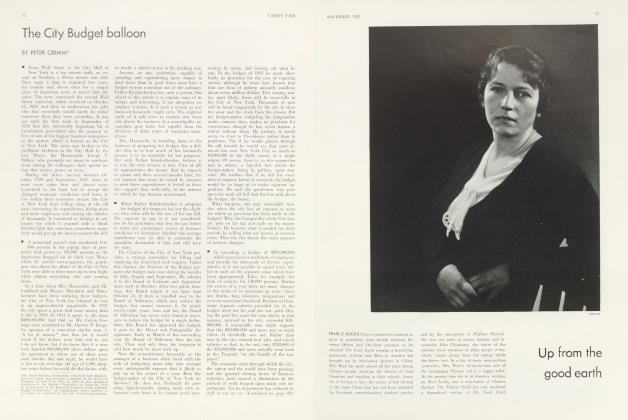

She tossed out the last of the crumbs and set her feet down on the floor. Here was her bedroom filled, for a wonder, with sun. And there in the glass, the reflection of the woman who had come to England to unbury the dead. She saw her own wise pale face with the deep lines of concern in the cheeks, and the heavy auburn braids wound twice around. Whatever grey there was in her hair lay carefully hidden underneath, concealed by the coils, as if the hands of a red Indian had been laid gently to her head. Almost forty, she thought grimly, and come to England to prove my identity.

She knew she belonged to the great: to the Earls and Dukes of Kingston-upon-Hull. The great, the great, she thought, and she turned again to look from the window. She had come to this place to lay her fingers on them. Dead great men to give her balance and background for her single life. She had never felt the want of money, but this other thing she had always wanted: the dignity of knowing what her own people had been.

"The Kingston titles became extinct on the duke's death without children on September 23, 1773," had been written, but town-records and family Bibles she would unearth to prove that this was not so. She wanted nothing the great might have left behind on earth, except the satisfaction. She was never at ease with the blood in her own body if she could not know where it had flowed before. If there were any great men living now, surely they never came through Kingston. She stood at the window thinking that if ever a man of proud blood set foot on the path that ran smartly up the garden, the doves would change their tune and the laurel tree would burst widely into flower. If ever a sign of the great came walking through the hedge below, the white kernels of the laurel buds would unfurl completely like corn popping in the pan. The doves would cease their moaning, and instead shout: "Caesar! Caesar!"

The first time the vegetable-man stopped his cart in the lane, all the doves rose out of the branches and went circling over the house.

The vegetable-man halted in the lane, and there called out the names of all his vegetables as if he were summoning them to rise. His face was bleached and fair under the singular gold lick of his pompadour. He wore his shirt-sleeves rolled up, and a pair of washable trousers. The horse in the shafts of his cart was slick and round and firm, and it cropped the half-apple off his palm, sneezed in a shower, tossed its bit in its mouth and lipped its master's bare light arm. The doves fled down and lighted on the side of the open cart, and Lydia held her breath at the sight of all this happening below.

In a little while, as she watched, two young goats as shy as deer came stepping down the lane as if in answer to his voice. They came to the brink of his shadow and nibbled shyly at the cabbage-leaves that the vegetable-man ripped off and threw away. Lydia saw that lie had a gentleness for animals, whatever kind they were; he had a special gift for each one of them and they followed behind him when he went away.

® The vegetable-man had slapped the horse's flank with the flat of his hand, and the beast lifted up one leg and then the other, slowly, laboriously, bearing the cart away. The two little goats went stepping delicately behind him, and into the boughs of the laurel tree the doves returned and paced hack and forth bemoaning. "Ah, God, ah, God!" they said in grief and dropped their Chinese white. And how strange, how strange, thought Lydia softly, that a man of the common people, a huckster, should have that wondrous gleaming poise and goodness in him. He seemed to her as clean and straight as a torch burning through frailty and through confusion to the very core of dignity that she had come to England to find.

On the third day that he came, she found she was going austerely down to buy a bunch of radishes from him. His clear blue eyes were on her as she took her pick. The little goats were shy of her, and the vegetable-man lifted one fair hand and laid it gently on the young goat's blunt-horned head.

"Good-afternoon," she said, and a curious agitation shook her.

"Good-afternoon, Miss," the vegetable-man said.

Just as she opened her purse, the doves came circling down around them. The flock of them settled in a row on the side of the cart and the feathers of their throats filled up with sound. The thin naked bird-feet clung quivering to the timber edge, and suddenly one dove dipped his head forward towards Lydia and snatched a radish-leaf from the bunch in her hand.

"Them's Barbary doves," said the vegetable-man. "I got Runts and Carriers at home as neat as anything you ever saw."

It was strange to hear him speak; strange that any man should speak of birds as though they were so dear to him. Lydia could not lift her eyes to his face as she paid the coppers out.

"Sometimes when the wind's wrong," said the vegetable-man, "there's any number of Carriers gets blown out of their way and comes down for shelter."

Lydia looked up at him. touching her brow with her hand as if to re-arrange her hair but shielding her eyes from his uncanny gaze.

"I takes them home and cares for them until they're strong enough to take to the air again," he said gently; gently as a mother might have spoken of her young. Gently, thought Lydia, as her own mother had never spoken. It was wrong for a man, for a young man to he so wise in mercy. Lvdia looked straight through his clear eves into the concern for what might become of a heart that stood there open like a refuge for any creature that cared to come.

"Carrier pigeons going over?" she murmured mindlessly to conceal her confusion.

"Pigeons or doves," said the vegetable-man. "It's all one and the same. Whatever you call them, they've all got a little ring around their foot, one just like the other. With a message sealed up in it just the same. I've had Frill-backs and Tumblers," lie said to her. "But the Trumpeters are the sweetest of them all."

Continued on page 62

Continued from page 36

"How do you know?" asked Lydia, and her throat was dry with wonder.

"They haven't no pedigree," said the vegetable-man. "They're rifT-rafT. That's what makes them the sweetest."

Lydia's heart went still for a moment, and she saw the melting eyes of the young goat under bis caressing hand, and the birds close about him as if he were endowed with pure Franciscan flesh.

The next day he passed, when she heard his voice calling out between the hedge-rows, she went down the stairs with her straw purse in her hand. Two English housewives were buying carrots and onions, with care, and the two little goats were straying in his wake.

"Good-afternoon, Miss," said the vegetable-man to Lydia.

"Good-afternoon," said Lydia. When she looked into bis pale eyes the colour flew into her face.

When the strange women returned to their houses, the ring-doves took courage and descended, murmuring, in a sudden gust of rain. The vegetable-man threw back bis head to scan the heavens.

"I don't like the looks of it," lie said to Lydia, and she saw the words taking shape in bis long strong lifted throat.

"Which way is the wind?" she said.

"It's coming off the channel," the vegetable-man answered. "It's a bad way for any birds as are up. It's sure and certain to blow hard tonight."

He stripped off the outer leaves of the cabbage she had chosen, and turned to see if He young goats found it to their liking, it comes of love, thought Lydia. All the endowment of perception that he has, it comes from nothing else but a wide brooding love. She saw him bent away, selecting the rosy faces of the apples for her. Everything he bad on the cart she wanted a part of. She wanted to climb back to her room with a sample to taste of everything he had tended and brought to fullness. And suddenly he turned around with the apples in his hands and said to her:

"I was talking to my mother last night about the colour of your hair."

Lydia's hand fled up to her heart and she saw the ring-doves whirl away.

"Ah, don't!" she said sharply. "You mustn't speak like that to me!"

His gaze was clear and guileless.

"It's such a pretty colour," he said. "I meant you no offense."

She turned with her vegetables, and without a word walked sternly to the rooming-house. Just as she passed the threshold, a remnant of wind spun about her head and unloosened a mesh of her closely braided hair; it licked across her eyes, straight out, as fierce as fire in the cheerless place.

In the day after the storm she went down into the garden and saw the havoc right and left. Here was a bough snapped off, and here the bruised flowers laid low by the rain. She walked the length to the end, and there under the hedge she saw a pigeon lying. His wings were stretched out as a cross from bis drenching breast, and there was a great hoop of naked flesh around each wounded eye. Lydia fell on her knees with a cry and lifted the grey bird up in her hands. He was living, for he stirred wildly in her fingers, and she laid his failing beak against her own warm mouth. She bore him up to her room and dried his feathers with the softest linen. She heard her own voice crooning above him, soothing and wooing him as she spread him, like a fan, before the fire.

"My darling, my darling," she whispered to the heedless scrolls of bis fine ears. She would have given all she possessed to know a few words of bis tongue.

About his ankle was the bracelet, just as the vegetable-man bad said it would be. And where it joined was sealed the little message near bis claw.

"You were so brave, so brave, my darling," she said to him. She could see him flying low in the storm over the anger of the Channel waves, flying all night from the other side, following the direction that his heart's compass told him was true. "You were so brave all night," she said, "and nothing shall ever harm you."

She wanted to pluck the terror from his eye and cast it forever away. She put the pigeon in a small basket and carried him on her arm to the little cottage where the vegetable-man lived in the village.

"I've brought you a pigeon that was blown down by the wind," she said. They stood looking at each other, but now she felt no confusion. "I knew you would take care of it," she said, "until it could fly on again."

"Yes," said the vegetable-man, and he put his hand in gently to lift the pigeon from the basket. "I'll put it in with the others," he said, and his hand brushed hers in passing. "It's skin and bone. I'll put it in the coop and feed it up for a day or two."

She followed him back to the wire place where a dozen or less pigeons were gathered, pecking at corn and flying little over the wet black mud.

"1 found them three this morning," said the vegetable-man, pointing out three drenched and shivering birds to her. The little green blinds of their lids were drawn up over their eyes. "They pick up over-night with corn and meal," he said, and he released Lydia's pigeon.

In the week, Lydia brought him two more pigeons who fell in the lane before the house, worn out by the wind that would not die. She set out in the morning with a bright easy sense of pleasure, and as she took the way to his cottage she could feel her heart beating soft with love. The birds were dear to her now, and the flowers that sprang up in the hedges, and nothing bad ever been dear to her before. It was the best time in England, it was May, and her heart was stirring wondrously with spring. When she thought of the dead, it now seemed that they had taken on life to her. She could fancy the Duchess of Kingston stepping regally down this very lane, shining with pleasure because she was going shamelessly to tryst with a common man, a countryman, and a tide of blood ran warm in Lydia's face. The sun was high above the trees and the vegetable-man and his mother had already sat down to table. When Lydia came breathlessly in through the door she found them sitting at either side of the cloth with their plates steaming richly in the sun.

(Continued on page 66)

Continued from page 62)

"Oh, I'm sorry!" said Lydia. "I just found another pigeon!"

"The fourth!" said the old woman. "Ah, you're too good to us, ma'am! If I set you a table to yourself, ma'am, would you sit down and have a bite to eat ?"

"Oh, no, I couldn't trouble you!" said Lydia, hut suddenly her eye fell upon the platter before them and she saw the shape of the food they were about to take: there were fresh peas from the garden set all around in the gravy, and in the center was the form of a little roasted bird. Her tongue was so parched that she could scarcely bring speech to it. She pointed with one finger at the bird on the plate.

"What happened, what happened," she said after a moment of terror, "what happened to the pigeon I brought on Monday?"

The vegetable-man shook his head and looked grieving at her.

"The poor little chap." he said with emotion. "He died during the night."

"Oh!" said Lydia. She felt her face go white and her heart was failing. "What about the two I brought on Wednesday?" she said. The walls of the room made a swoop like the flight of birds. And still the vegetable-man stood shaking his head in grief at her.

"Dead," said the vegetable-man and he opened his empty hands before her.

"Henry has a painless way of doing away with them," said the little old woman brightly. "He just holds their heads under in a glass of water."

"Oh!" said Lydia. "Oh!" she said, and she picked up her little basket. She felt her blood shuddering and shuddering throughout her body. "Yes," she said, "oh, yes, painless." And she fumbled her way out the door.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now