Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOn the trail of the champs

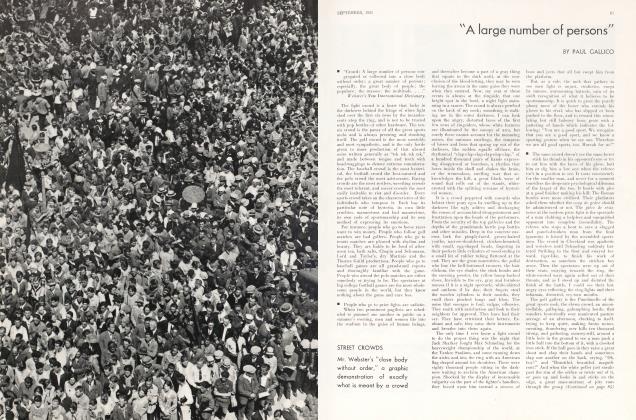

PAUL CALLICO

■ The trail of the champions, after cutting through the New Madison Square Garden Bowl in Long Island City where Sharkey ignobly stole his heavyweight title from SchrneIing, and meandering over the greens and fairways of Fresh Meadow, where Gene Sarazen played the most amazing round of golf in Open Championship competition, swerved sharply westward across the continent into the City of Los Angeles. Here the athletes of the world had gathered for the games of the 10th Olympiad. From there, the trail led through Cleveland, where the airmen raced, their attendant death-skeleton perched on the wings or hanging with a grin from the undercarriage, into Detroit, where the thunderboats clove Lac St. Clair—oddly enough, carrying the same unwelcome passenger—from there, into Baltimore, and back to New York again. Camp-followers of the battles of Champions, we pursued the heroes over the skyways. . . .

■ Flying over Kansas City, on the first leg of the Transcontinental Flight, the TWA airliner tipped one tin wing earthward, before it began to slide into the airport. It was 8:30 in the evening, and the people, black specks below, were straggling along the levee. For a moment we thought we saw Captain Andy, Parthy and Magnolia on the quay, but it was probably an illusion of tlie dusk. Now we could see the showboat anchored in the muddy river. The tri-motor sat down, and when the propellers stopped beating their thunder from the air, and our ears functioned again, we heard the steamy, breathy, nostalgic music of the showboat's calliope floating over the Missouri.

In the morning we fly out of Kansas, over the romantic Cimarron, and the Texas Panhandle, the bad lands and dead lands, and volcanic territory that we never knew existed in our own country, over lava beds and lava pots that look like the fumaroles of the Galapagos from the air, and over the Rocky Mountains—or rather, through them. The big metal ship finds a pass just this side of Albuquerque and buzzes through. If you liave been dozing and suddenly look out the window, the effect is startling. For a moment, you might think yourself in the dining salon of an ocean liner during a storm, looking out through the portholes on the sloping sides of mountainous seas. Now the gray stone waves of the Rockies roll away on either side of the ship. The Great Divide is impressive even from the air. where nothing is very impressive, because we are so impressed with our own courage in flying through it. Walnut Canyon is a red wound in the earth. The Black Mesa passes below in chunks. After Kingman, we fly over the Needles, unkempt crags that reach stony fingers into the sky, clawing for our wheels.

The sun that we have been chasing westward goes down, painting breathlessly lovely pictures. The colored mesas turn from pink to deep crimson. The mountain peaks shine like the gold spires of fabulous cities. The ship seems to float lazily, peacefully between the ragged earth and the dying day. The mountains show steel blue, deep purple, battleship gray, and then become black, shapeless masses that are felt, rather than seen below.

The airway approach to Los Angeles at night is so splendid and so awesome that it should be set to deep and soaring music, not to words. First, there are only the stars overhead, darkness below, and the flying disk of the moon, then the black wall of the Coastal Range, the last barrier to the Pacific Slope. The altimeter needle moves higher . . . higher. .. . You slip over the high fence of the continent, and are floating, suspended between stars and stars, between a canopy of diamonds and the carpet of topaz, as the myriad lights of the San Bernardino Valley, Alhambra, Pasadena, Hollywood and Los Angeles come into view.

The ship glides down to the floodlit concrete of the airport at Glendale, and it suddenly loses all of its celestial grace, as it bumps clumsily to the terminal. Here we are greeted by the inevitable crowd of airport gapers, who seem to look surprised that we got there, that we are still alive. We are then immediately driven through white streets, past white houses illuminated by glaring unhooded lights. From the air, the lights were a pattern of jewels, but now looking out of the cab window, we see that they are fastened to gasoline stations which are like a dipsomaniac's conception of the Taj Mahal, sandwich stands built for no apparent reason, to resemble merry-go-rounds, gigantic plaster polar bears, ice cream cones, frankfurters and oranges. In their plaster innards there are edible replicas for sale.

® The Olympic Games are remembered aan incredible saturnalia of muscle, might and sweat, a fourteen-day orgy of competition spattered over an area of thirty square miles or more. If you had been a giant flea you might have hopped in one day from the Olympic Stadium, where you had witnessed the poetic running of Ben Carr to the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, to see the cyclists spinning their colored webs around the board track; then to the Marine Stadium at Long Beach, noting in passing the ugliness not without charm of the forests of oil derricks that line the way. At the Marine Stadium there were the oarsmen punching their spaced circles on the surface of the 2000 meter water course.

Another hop would take you to the Riviera Country Club for the Equestrian events, the brilliant pageant of High School horses and slim, wiry men in opera bouffe uniforms. Still another leap would have taken you across Point Firm in in Los Angeles Harbor, where the white wings of the yachts dip against tbe ultramarine of the Pacific, landing you at the Elysian Park Pistol and Rifle Range, where tbe small arms banged ceaselessly from morning until night; then back to Olympic Park and tbe high banks of the Swimming Stadium, where the slim bodies of boys and girls, clad in black silk, shone like sleek young seals in the blue waters.

Continued on page 62

(Continued from page 39)

However, being only a sports reporter, you are limited by the cruising radius of a Packard roadster. You start the day in the fencing armory where the rafters ring to the singing of steel blades. Then you wander over to the Stadium for deeds of speed and strength afoot, and vault over the wire fence beside the pool just in time to catch those yellow-haired Olympic sweethearts, Georgia Coleman and Mickey Riley, performing from the thirty-foot diving tower. Note the smooth action of Eleanor Holm's backstroke and the freshness of her face framed in the foam of her own stirring, before you return to the Stadium in time to hear the first fanfare of trumpets announcing the return of the marathoners. The swart, youthful Zabala of the white teeth, white helmet and black hair, leads the weary pack back into the bowl, and past the flaming peristyle to the finish line.

There is wrestling or boxing at night in the auditorium, but we can still find time to drop in for dinner at the Chapman Park Hotel, the headquarters of the women athletes. This is the "Muscle Mollary" of the world, by far the most fascinating zoo of all the fascinating zoos in Los Angeles.

Here are quartered the tall, angular, lantern-jawed, slat-ribbed sisters from England and South Africa and Australia; the round-bosomed, round-hipped yellow-haired Mädchen from Germany and the north countries, the small, solemn, full-lipped, unsmiling, Japanese girls with straight, coarse black hair; Dutch girls, French girls. Polish girls, Canadian girls, Danish girls, and a hundred or so American girls, all eating in the same dining room, clad in uniform coats, skirts, sweat-suits, silk swim pajamas, sweaters, frocks, and middy blouses. Most of the lady track athletes are forthright and bluntly ugly. Mannish women with close cropped hair, coarse features and powerful lumpy, unfeminine bodies. The swimmers, except for a certain breadth of shoulders, have the best figures. We are conscious at all times that through these women's teams runs an intense undercurrent of jealousy, spite and petty cabal.

When considered in the light of the great athletic performances, the things we remember from this great sports show are absurd and somehow insignificant : The missing banners from the second story of a building on Wilshire Boulevard, removed at 4:00 A.M. the morning after her last event, by the incredible Babe Didricksen, who, in ecstasy at the conclusion of her share in the exercises, somehow scrambled up the face of the edifice in the company of a bevy of sister vixens, and pulled the banners down, for souvenirs; the fact (learned from a Japanese swimmer) that the Japanese picture writing word for "noise" is "woman" repeated three times—the joyous but internationally pregnant moment at Olympic Village when the Finn hammer thrower, practising his art, let fly too soon, and sent his cannon ball through the side of a Swede's bungalow, ripping off part of the roof, destroying the plumbing and taking the rear wall out with it as it carried on; the charming aftermath when the Swede (who luckily was out during the bombardment) came home, construed it as a deliberate act of war, got out his javelins, and went looking for the Finn. . . .

Male athletes who break training get drunk. Some lady athletes, when they break training, get drunker. Eddie Tolan wears a bandage on bis left knee because be is superstitious. On the last day, the sun vanished behind the rim of the Stadium at the precise moment when the flame that burns night and day atop the peristyle during the games, was extinguished.

The muscle champions were done. The sky trail pointed to Detroit; turn left at Columbus, as far as the lake, left again as far as Toledo, and then, first right. Look for the big black and orange striped gas tank just the other side of Detroit and Cleveland, straight across the lake, and first turn to your left. You find the speed champions competing on the water, and in the air.

We wanted to go for a trial-ride with Gar Wood in Miss America before the Harmsworth Trophy Speedboat Race. We also wanted to see some of the air races taking place in Cleveland, and we wanted to do both on the same day. This necessitated our being in Detroit in the early morning and forenoon, and in Cleveland in the afternoon. We solved this problem in space and time by chartering an ancient Ryan monoplane driven by a kid pilot, and commuting between the two cities, a matter of an hour and a half if we follow the shore line, and fifty-five minutes if we risk our skins by flapping a crow's flight across Lake Erie.

Looking down on the Cleveland Airport where the races were taking place was like looking at the "favor counter" in a five and ten cent store where you can buy little red. yellow, blue and green lead replicas of planes and pylons. Getting down out of the air is always a thrill, because we feel that at any time some other ship with the same idea, hidden by our wing, might sit down on top of us.

It is also a curious sensation to sit in a grandstand and watch two racing ships lock wings on a turn, and spatter themselves over the ground and vanish in a pyre of dust. Ambulances, sirens a-moan, tear onto the field, white-coated internes remove the quiet, shapeless forms of the pilots and bear them off to the hospital.

In Cleveland, A1 Williams, ex-baseball pitcher for the New York Giants. ex-Lieutenant in the U. S. Navy, and now a flying scientist, does things with planes that no one has ever done before, in order to discover what will happen if someone ever has to do them in an emergency. He broadcasts while flying upside down, rounds pylons on his back, and climbs the outside of an imaginary hoop; Benny Howard builds and flies light aluminum racing ships that are so small they have to get him into them with a shoe-horn; fliglitComtnander Atcherly. a daffy Englishman. and one of the greatest fliers in the world, dons a Prince Albert coat and high hat, hangs a string of laundry from the struts of bis training Jenny, and clowns in the air— comic, dangerous clowning—only fifty feet from the ground.

(Continued on page 67)

(Continued from page 62)

Jim Doolittle, who hurtles his engine and a pair of stubby kiwi-like wings through the ether at 300 miles an hour is an ex-army pilot. He is a small, sandy-haired man with deep-set blue eyes. He has bailed out of several ships, and emerged from some serious crack-ups unscathed. One night in South America he got a little tight and stepped off a six-foot balcony. He broke both legs. This, of course, is a typical story of how daredevils get hurt. The part of the story that is not typical is how, having a flying date on the other side of the Andes, which he felt in honor bound to keep, Jim Doolittle flew over the roof of the world alone, with both legs set in a plaster cast....

Meanwhile, in Detroit, Car Wood was puttering over the tons of engines in Miss America. She hung suspended in dry-dock at Grayhaven. He raced Kaye Don in Miss England III for the Harmsworth Cup, and the race was a fizzle because the Englishman's engines packed up. Wood had never had his new cup defender wide open until two days before the first heat, that cool, gray morning when he took us out on the Detroit River. Helmeted. padded, goggled, stuffed, he waved to Johnson, his mechanic, to open her up wide. We knew then that we were riding with a gay madman, because the white-headed Car grinned and flashed his teeth. We went 122 miles an hour, and we made boat history that day.

We watched from the water the first of the cup races. For the second, on Labor Day, we chartered a Loening Amphibian. We flew over the course in the early morning as the orange sun bounced up off the treetops of Belle Isle Woods. Banking steeply around the course at 500 feet, we saw the black smoke and bright yellow flame spurt from the Englishman's stacks after the first lap, saw his mechanic, a speck in white, crawl aft and tinker frantically with the engine. We circled the bright silver boat until she died, and her own furrows on the water's surface caught up with her....

Thus the trail of champions, and thus, too, the enviable life of a Boswell to these athletic Johnsons. Now we take the train to Speculator, New York. It is a nasty, crawling, shaking, sooty train. We get a quick glimpse of Herr Schmeling rehearsing for a match; then by air to Baltimore, aboard a huge 20-passenger Curtiss Condor. Here the amateur golfers wrestled with their souls, and the terrain of Five Farms. An old champion passed, a new one was born. The road led to Salem, Massachusetts, where the girl golfers played their championship, back to New York to see two heavyweight bruisers in Madison Square Garden, off to Chicago over the Alleghanies. From the sky they look like furrows scratched by an enormous plow. Through the football stadia of the east and west....

The trail may grow cold in the coming months, but in the spring, the Ball Clubs will head south, the fish will start schooling, golfers, tennis players will begin to swing their implements. and your faithful reporter will again shake the lead from his shoes, chuck some stuff into a bag, grab his trusty machine and continue his relentless pursuit of the champions.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now