Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIce hockey—sometimes known as shinny

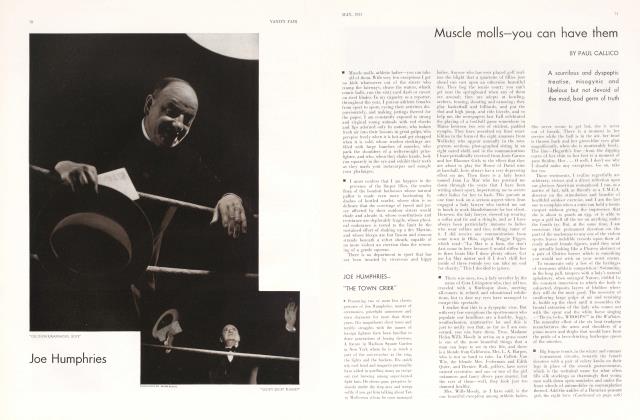

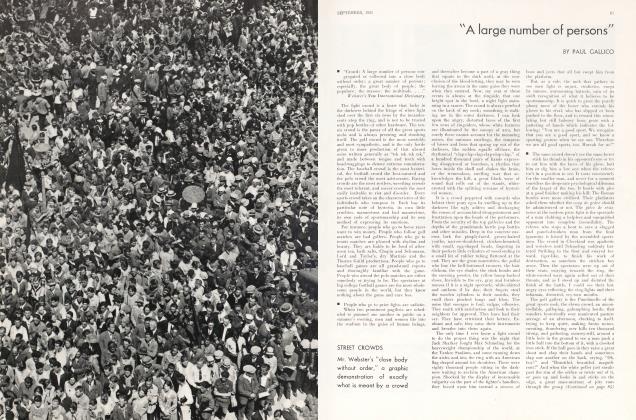

PAUL CALLICO

A veteran sports writer follows the flight of the puck, and concludes that this is a game for heroes

The tremendous popularity of the game of professional ice hockey in this country may be analyzed with considerable simplicity. It is played by a group of the most violent and reckless men on the face of the globe, on a surface which makes it the fastest game in the world. The players wear knives on their feet and carry clubs in their hands with which, when aroused, they beat one another over the head—fists being used only in cases of mild pique. It is the only game that, with a keen understanding of the fundamentals of the drama of conflict, embodies a sound sense of the comic and the ridiculous. Each sextette, in the person of the absurd and overstuffed little goalie carries its own May Vokes around with it.

The men who play on the teams are of the same type that went to make up the regiment known during the war as the Princess Pats. They are improvident desperados, impervious to physical pain, hot-headed, truculent, grudge-bearing and completely fearless. An ounce—a gram—of prudence and the big league hockey player is ruined. To skate headlong into a melee of thrashing sticks, flying knees, elbows, and skidding feet—the shoes of which are armed with nine inches of razor sharp steel, calls for valor verging on foolhardiness. There are no cowards on a hockey team. The average price of admission is three dollars to see twelve proven heroes pursue, foil, belabour, slash and wound one another. That makes four heroes for a dollar which is reasonable, even in these days.

The game is simple except where its commercial exploiters have complicated it with certain rules, regulations and restrictions cunningly calculated to satisfy the customer's desire for blood-letting and skull cracking, and still in a measure conserve the available supply of major league hockey players which is limited.

There are six men on a side and they pursue a small, black hard-rubber disk up and down a skating rink some 200 feet in length, each with intent to ram the missile into the other's goal. This is constructed of netted

cord, the mouth of which is six feet wide, and in front of which, in defence, stands the goalie. Since the widest goalies that come are only about 22 inches across, that leaves a considerable gap on either side of him to be filled, and part of the evening's entertainment consists in observing the efforts of the goalie to spread and arrange his anatomy so as effectively to take up this treacherous space.

However, if this were all there was to it, the game would resolve itself into one continuous and fatal Donnybrook in front of one goal mouth or the other, with carnage unspeakable. To prevent this the rink has been divided into three zones marked by trisecting blue lines, each zone has its own restrictions and penalties, and the players fight their way through a welter of rules second in number and complications only to football, and having to do with the passing of the puck, the carriage of the hockey stick, or shillelagh, the number of attackers, the methods of defence, tripping, butting, cross checking, slamming into the board fence that rims the rink, mayhem, felonious assault, and the carrying of knives, or other concealed weapons with intent to kill. Two referees are provided to interpret these rules and decide whether the bashed skull, or slit weazand of any of the competing athletes occurred as the result of foul intent, or merely a deplorable accident.

To do this properly and with justice, the arbiters keep themselves well posted on all of the bitter feuds that spring up between players of opposing teams. These are lasting hatreds of the Hatfield-McCoy type and never seem to burn out. When one player suddenly sinks to the ice and dyes it red where he lies, and the referee notices a well known enemy of his anywhere in the vicinity wearing an innocent expression, in nine cases out of ten he dispenses with what is known as the benefit of the doubt and metes out punishment. And in eight out of nine cases he is right.

This punishment takes the form of banishment from the ice for a short period of time, depending upon the nature of the penalty.

This time the criminal spends in an improvised juzgado at the rinkside known as the penalty box. His team suffers along with him, because no substitutes are permitted to replace him, and during the length of his sentence they play five men against six. Under the old rules, that is to say 1929, when some of the boys would get a little bit hasty with one another, the Boston Garden, or Madison Square, or the Coliseum in Chicago would ring with the hysterics of the audience as two lone players, all their comrades in the clink, would stand off the attack of six goal hungry athletes.

Possibly the overwhelming excitement of this spectacle was considered dangerous to ladies with nervous hearts, and old gentlemen with high blood pressure, because the officials modified this rule this year so that no more than two players from one team may be absent from the ice at one time.

However, the penalty box still remains a delightful breeding place for beautiful friendships, since both participants in any little unpleasantness that should break out on the ice are sent to sit side by side in a space as confined as a telephone booth in a United Cigar store, and as a further quaint touch, neither criminal is relieved of his weapon upon entering the jail, at the side of the ice rink.

When a fight occurs on the ice there is no such thing as an innocent party. The referee thumbs two brawlers off the premises, whereupon they are ushered into a tiny space to sit next each other, their bodies still steaming from their clash. They jostle, they elbow, there is a brief exchange of—"O-I-amam-I" and "why-you-dirty-so-and-so." One of them produces his brassie, which in the interests of peace might better be checked at the gate, and blooie! the riot is on. The players on the ice swarm over, there is a great waving of mallets and throwing of punches, the referees and the special police dive in and the sum total of damage is revealed to be the ruining of the hard hat or skimmer of an innocent bystander whose seat was next to the penalty coop.

The spectators love these impromptu battles, and the players rather fancy them themselves, the participants rarely get hurt and the arena is sold out in advance for the next game between the warring teams. I do not wish to insinuate that these riots are conducted on a business basis, hut merely that the hockey magnates are not quite as shocked and hurt as they appear to be when they occur.

When one or two stars are languishing in durance vile for a two minute period, or five minutes, if the dumping of a player appears to have had an atmosphere of premeditation about it—or twenty minutes if the victim bleeds or lies unconscious—that player's team is undeniably handicapped. Therefore the perpetrators of these quondam assaults are trained from infancy to compose their features at all times into bland and simple expressions, which has led to the approved simile—"he looked as innocent as a hockey player who has just hamstrung an opponent."

(Continued on page 94)

(Continued from page 71)

The feat, however, is to spill an opponent who threatens with the puck or who might be in a position to receive a pass, and so mask one's features that the referee casting about for the guilty party takes one look and says—"There skates an innocent man." I assure you that this art is seriously practiced, and reaches its height when a player dumps another so artistically, and himself wears such an injured countenance, that the referee penalizes the fellow who has been spilled for unnecessary roughness, or high stick, or dandruff.

There is no game in the world that moves so swiftly, so speedily, so continuously, and so poetically. You forget that the playing surface is ice and suddenly become part of an illusion, whereby men who seem to belong to a strange and super race are moving at incredible rates of speed, with all the lovely grace of wheeling birds. Hockey is full of rhythm, and the music of motion, but they are the halt rhythms of jazz, the stop-go, go and stop syncopations. They seem sometimes to be skating George Gershwin and Jerome Kern out on the rink, lyric passages broken up by the braying of brasses, as the sticks suddenly clatter and clash in a mid-ice scuffle for the puck, or which stop breathlessly and begin a new theme, as a clever center breaks up a solo rush by stealing the puck away with a poke check, the prettiest play in the game.

Finally, it is the only other game besides polo regularly patronized by society, due I suspect to three factors, its excitement, its honesty, and the temperature in which it is played. No woman ever looks lovelier than when she is in evening dress with her sable or ermine wrap thrown over her shoulders. Thus hockey in three years has become a serious rival of the theatre and Opera. Les belles dames sans merci can wear their furs in the boxes all evening.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now