Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now"A large number of persons"

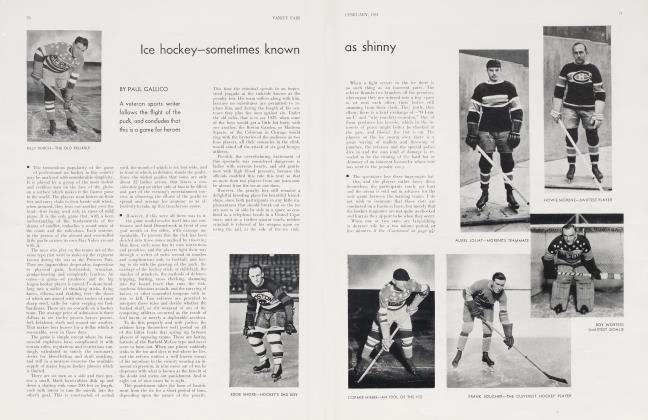

PAUL CALLICO

"Crowd: A large number of persons congregated or collected into a close body

without order; a great number of persons; especially, the great body of people; the populace; the masses; the multitude. . .

Webster's New International Dictionary.

The fight crowd is a beast that lurks in the darkness behind the fringe of white light shed over the first six rows by the incandescents atop the ring, and is not to be trusted with pop bottles or other hardware. The tennis crowd is the pansy of all the great sports mobs and is always preening and shushing itself. The golf crowd is the most unwieldy and most sympathetic, and is the only horde given to mass production of that absurd noise written generally as "tsk tsk tsk tsk," and made between tongue and teeth with head-waggings to denote extreme commiseration. The baseball crowd is the .most hysterical, the football crowd the best-natured and the polo crowd the most aristocratic. Racing crowds are the most restless, wrestling crowds the most tolerant, and soccer crowds the most easily incitable to riot and disorder. Every sports crowd takes on the characteristics of the individuals who compose it. Each has its particular note of hysteria, its own little cruelties, mannerisms and bad mannerisms, its own code of sportsmanship and its own method of expressing its emotions.

For instance, people who go to horse races want to win money. People who follow golf matches are bad golfers. People who go to tennis matches are pleased with rhythm and beauty. They are liable to be fond of afternoon tea, bath salts, Chopin and Schumann, Lord and Taylor's, dry Martinis and the Theatre Guild productions. People who go to baseball games are all grandstand experts and thoroughly familiar with the game. People who attend the polo matches are either somebody or trying to be. The spectators at big college football games are the most wholesome people in the world, but they know nothing about the game and care less.

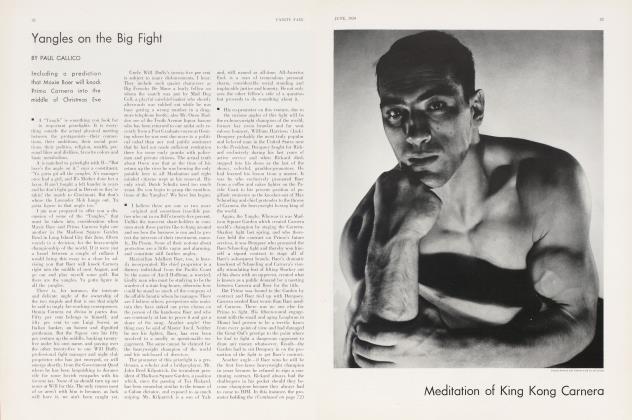

People who go to prize fights are sadistic. When two prominent pugilists are scheduled to pummel one another in public on a summer's evening, men and women file into the stadium in the guise of human beings, and thereafter become a part of a gray thing that squats in the dark until, at the conclusion of the blood-letting, they may be seen leaving the arena in the same guise they wore when they entered. Now, my seat at these events is always at the ringside, that one bright spot in the bowl, a night light swimming in a saucer. The crowd is always perched on the back of my neck; something is stalking me in the outer darkness. I can look upon the angry, distorted faces of the first few rows of ringsiders, whose white features are illuminated by the canopy of arcs, but surely these cannot account for the menacing noises, the ominous rustlings, the tempests of hisses and boos that spring up out of the darkness, like sudden squalls offshore, the rhythmical "clap-clap-clap-clap-clap-clap," of a hundred thousand pairs of hands expressing disapproval or boredom, a rhythm that bores inside the skull and shakes the brain, or the tremendous, swelling roar that acknowledges the kill, a great black wave of sound that rolls out of the stands, whitecrested with the splitting screams of hysterical women.

It is a crowd peppered with cowards who bolster their puny egos by swelling up in the darkness like ugly adders and discharging the venom of accumulated disappointment and frustration upon the heads of the performers. From the security of the top galleries and the depths of the grandstands hurtle pop bottles and other missiles. Deep in the concrete caverns lurk the pimply-faced, greasy-haired youths, narrow-shouldered, chicken-breasted, with small, egg-shaped heads, fingering in their pockets little cylinders of wood ending in a small bit of rubber tubing flattened at the end. They are the great nonentities, the polloi who buy the bell-bottomed trousers, the hair slickum, the eye shades, the stink bombs and the sneezing powder, the yellow hump-backed shoes. Invisible to the eye, gray and formless masses if it is a night spectacle, white-shirted and uniform if by day, their fingers steal the wooden cylinders to their mouths, they swell their pinched lungs and blow. The noise that emerges is foul, vulgar, offensive. They smirk with satisfaction and look to their neighbors for approval. They have had their say. They have criticized their betters. Exultant and safe, they raise their instruments and breathe into them again.

The only time I ever knew a fight crowd to do the proper thing was the night that Jack Sharkey fought Max Schmeling for the heavyweight championship of the world, at the Yankee Stadium, and came running down the aisles and into the ring with an American flag draped around his shoulders. There were eighty thousand people sitting in the darkness waiting to acclaim the American champion. Shocked by the display of inexcusable vulgarity on the part of the fighter's handlers, they loosed upon him instead a sirocco of boos and jeers that all but swept him from the platform.

But, as a rule, the mob that gathers to see men fight is unjust, vindictive, swept by intense, unreasoning hatreds, vain of its swift recognition of what it believes to be sportsmanship. It is quick to greet the purely phony move of the boxer who extends his gloves to his rival, who has slipped or been pushed to the floor, and to reward this stimulating but still baloney beau geste with a pattering of hands which indicates the following: "You are a good sport. We recognize that you are a good sport, and we know a sporting gesture when we see one. Therefore we are all good sports, too. Hurrah for us!"

The same crowd doesn't see the same boxer stick his thumb in his opponent's eye or try to cut him with the laces of his glove, butt him or dig him a low one when the referee isn't in a position to see. It roots consistently for the smaller man, and never for a moment considers the desperate psychological dilemma of the larger of the two. It howls with glee at a good finisher making his kill. The Roman hordes were more civilized. Their gladiators asked them whether the coup de grace should be administered or not. The piece de resistance at the modern prize fight is the spectacle of a man clubbing a helpless and vanquished opponent into complete insensibility. The referee who stops a bout to save a slugged and punch-drunken man from the final ignominy is hissed by the assembled sportsmen. The crowd in Cleveland was apathetic and voiceless until Schmeling suddenly battered Stribling to the floor and swayed forward, tiger-like, to finish his work of destruction, as somehow the stricken boy arose. Then the spectators were up out of their seats, swaying towards the ring, the white-crested wave again rolled out of their throats, and as I stood up and dictated the finish of the battle, I could see their hot, angry eyes reflecting the ring-lights and their inhuman, distorted, cry-torn mouths.

The golf gallery is the Punchinello of the great sports mob, the clown crowd, an uncontrollable, galloping, galumphing horde, that wanders hysterically over manicured pasture acreage of an afternoon, clucking to itself, trying to keep quiet, making funny noises, sweating, thundering over hills ten thousand strong, and gathering, mousey-still, around a little hole in the ground to see a man push a little ball into the bottom of it, with a crooked iron stick. If the ball goes in they raise a great shout and clap their hands and sometimes slap one another on the back, crying, "Oh, boy!" and "Beautiful, beautiful, magnificent!" And when the white pellet just sneaks past the rim of the orifice or twists out of it, or goes up and looks in and sticks on the edge, a great mass-murmur of pity runs through the group and they sound their "Oh's" like a Greek chorus greeting the arrival of a new set of catastrophes. Then it is that they make their absurd clucking noises and shake their heads, some in unison, some in anti-unison, like mechanical dolls all set off at once.

Continued on page 84

Continued from page 67

There are curious psychological undercurrents to this. They want the celebrity who has missed the putt to know that they are all golfers, too; that they have been in the same position; that Fate once treated them as shabbily; and that they are really brothers in misery. It isn't quite the same thing that makes a theatre audience applaud a difficult tap or acrobatic step, to show that they know a good one when they see it; but it's something like that.

The golf gallery is closest of any to the game that is being played. Every individual in the stampede is familiar with the implements used and the problems that arise from tee to green. They are really vicarious players, and the crass outsider who rattles a toy movie camera at one of the artists just as he is about to apply a delicate brush of his poker against the side of the quiescent ball, is given the hissing and glaring-at of his life. The Jones galleries were something to see, up and away over the hills before the master had completed the poem of his follow-through, running, crowding, tearing, galloping, hustling—men, women and children, in sunshine or in cloudburst, their tongues hanging out, their faces red, their sports clothing dishevelled, elbowing one another in the wild route over the lea to secure a momentary vantage point from which to bear witness to the next miracle.

The tennis audiences were always my favorites, preening themselves, bestowing refined approval in well-bred and well-repressed little outbursts, beaming upon the contestants and on one another, glaring at someone rustling a piece of paper, expressing righteous indignation at the unwelcome intrusion of an ordinary spectator who vulgarly screams, "Come on, you Johnny, sock it again!"

Look at them broadside during the life of a long rally, with the ball skimming back and forth over the net, and you will see them give you a head dance worthy of the Tiller or Albertina Rasch coryphees, as their noggins move, in perfect unison, all to the right, all to the left, all to the right, all to the left, following the flight of the ball. They are experts at registering shocked and delighted approval when an erring player cries "Nuts," or "God damn," to let them know that they feel he has been a muggins, but withal a virile and manly one. They, too, hum with smug sympathy when a player pouts or makes a move at a missed ball, pat-a-caking their hands to indicate recognition of the fine points of the game, and rooting for the player with the most slickum on his hair. I once saw a new world's record for the high dudgeon set at Forest Hills by a group of spectators around a baseball fan who must have strayed into the stadium under the impression that the Bushwicks or the Dexter Park All-Stars were playing there. When a high lob drifted into his territory, he caught the ball and stuffed it into his pocket, as he had been accustomed to dispose of foul tips captured in the ball yard. A uniformed attendant forced him to disgorge and the tut-tutting could be heard all the way to Queens.

Baseball and football crowds are happiest when they feel that they have become a part of the game that is being played for them. The solidly packed football stands begin to chant, "We want a touchdown," or "Hold that line!" And when the touchdown is scored or the line holds, the crowd takes part credit. In baseball, sections of the rooters set out deliberately to rattle a pitcher with rhythmic or anti-rhythmic hand-clappings, whichever they think will annoy *him the most, or by setting up a bedlam of sound, or by waving somewhat cloudy pocket-handkerchiefs at him. Most rooting, as a matter of fact, grows out of the individual spectator's desire to identify himself with the proceedings on the field, to shake himself free of the anonymity of the crowd and become an active participant in a sport for which nature happens not to have fitted him.

The loveliest girls in the world sit in the football crowds, their fresh faces framed in fur. The toughest babies in town seem to collect at the ball games, idle sisters sitting in pairs chewing gum, fanning themselves with their score cards and adding their harsh screams to the hullabaloo that accompanies a sharply hit ball or the race between ball and man for the base. The baseball crowd is cosmopolitan. It contains representatives from every walk in life and from every profession. It is the most expert gathering in the world, and the most appreciative of skill. The crowd of sixty thousand that sits in the Yankee Stadium on a Sunday afternoon in midsummer, and the World Series crowd of the same number that watches the interleague play-off in the fall, are as different as black and white, although both are looking at the same game. World Series spectators aren't regular baseball fans. Most of them have never seen a game before. They are drawn by the ballyhoo, the publicity and the higher prices. They sit on their hands and refuse to warm up to the rising and falling tides of battle. The bleacher crowd gets a better view of the game than the snootier patrons in the stands and boxes. They see the game the way the players see it.

Horse-racing crowds are nervous, greedy, fortune-hunting, always milling and moving about, whispering, circulating, muttering until the wheeling ponies suddenly freeze them into a temporary immobility, feverish in its intensity, the same pregnant calm that falls upon the onlookers when the little pill is hippity-skipping on the whirling wheel, between rouge et noir.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now