Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowVicious spirals

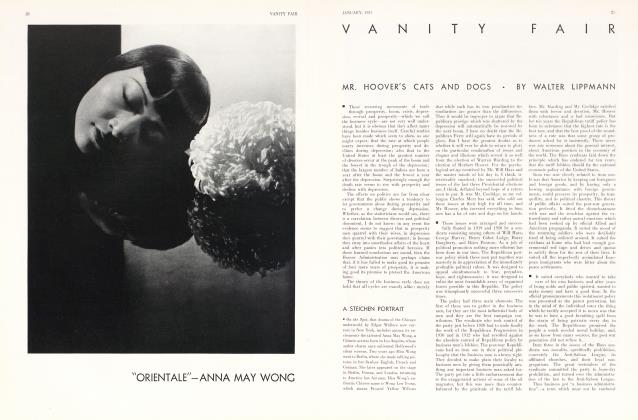

WALTER LIPPMANN

Why the depression must ultimately be ended by sacrifice and patriotism on the part of our citizens

As this essay is written in the middle of April, 1932, it is no longer entirely true to say that we are merely experiencing the effects of the folly and miscalculation of the war and the post-war period. We are in a phase when it may be said that the crisis is provoking itself and that the damage being inflicted upon mankind is immeasurably greater than the original causes would warrant. The crisis is now generating its own destructiveness by a kind of incest of its own consequences. It is customary to describe this process by saying that human affairs are caught in a vicious spiral of deflation. It is necessary to have a clear conception of this spiral if we are to understand the nature of the remedies which are required to deal with it.

Let us begin then by fixing in mind how this process has been working here at home in the last two and a half years. I shall ignore for the moment the causes which set it in motion and talk only of the depression period itself. It began with a contraction of credit. This was followed by a fall in the prices of stocks. Commodity prices fell. Production declined. Sales were reduced. Unsold goods piled up. Profits shrank. Workers were laid off. Wages were reduced. Purchasing power diminished. Confidence was impaired. Banks failed. Loans were called. Money was hoarded. Credit had to contract further. Prices fell still more. Production declined still more. Profits became deficits. Unemployment increased. Confidence was impaired still more. Credit contracted further. And so on and on and on.

As the price level has been sinking credit has been contracting which in its turn lias been dragging down the price level. The viciousness of the spiral is such that in its downward movement it has undermined not merely the crazy financial structures of the boom but many structures which would be sound under any conditions except those which the sheer malignancy of the crisis itself is producing.

If this rough description is essentially accurate it is obvious that it is necessary to intervene at some point in this spiral and by special measures to arrest its progress. Precisely because the spiral is vicious, producing its own causes of economic rot out of its own effects, it is not possible to hope that it will find its own point of adjustment and stabilization. The classical economic theory assumes that this will happen. But the classical theory presupposes an economic system in which prices, wages, and debts are flexible to a degree which under our system they are not. Our system is not self-adjusting and when it is caught, as it now is, in a circular process of deflation, the maladjustments become greater rather than less as the process continues.

The practical question, therefore, is to find the most likely point in the spiral and the most promising measures for a deliberate intervention.

There is now rather general agreement that the point at which it is necessary to intervene is one which will stimulate investment. It is necessary not only to stop the calling of loans and the contraction of credit but to produce a resumption of lending and an expansion in the use of credit. There are two sides to this problem. The creditors, which means in the first instance the banks and in a second stage the investing public, have to be reassured that there are ample reserves of credit available. This is essentially the task of the central hanking system, that is of the Federal Reserve Banks. Then the borrowers have to be encouraged to use the credit, that is to resume operations and thus provide employment.

On the lender side four things had to be accomplished before the Federal Reserve System could adopt a policy of bold credit creation. Its guiding minds had to be converted to the idea, in itself no mean task. The System had to be made independent of foreign obstruction; it had to regain its independence by freeing itself from self-imposed restrictions which bound it too closely to the vagaries of the international gold standard as it now operates. This has been accomplished by the Glass-Steagall bill, which is essentially a measure to undo the sterilization of the American gold supply. Third, the drain of deposits had to be stopped which meant stopping bank failures. This the Reconstruction Finance Corporation has, as I write, measurably succeeded in doing. Finally, the government had to evince a willingness to close up its deficit by taxation and retrenchment so that the banking system as a whole could feel free to proceed without being threatened with endless demands from the government.

Here at the end of April it may be said that the Federal Reserve System lias committed itself to the creation of as much credit as may be needed to take the member banks out of debt and make them so liquid that they could resume lending and investing. This raises the other side of the problem which is whether private industry is solvent enough and courageous enough to use the credit which will become available. If it is not, if business remains deflationary in its mood, then by public action it will be necessary to go further. There are two things that can be done here. One is to have a government agency, like the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, tap the revenues of credit and furnish it to railroads, public utilities and public authorities in the form of secured loans to be employed on revenue-producing enterprises, that is to say on enterprises which do not add to the dead weight of the public debt. A good example of this sort of thing would be a loan to the Pennsylvania Railroad to electrify its system. Another example would be a loan to the City of New York to build a vehicular tunnel under the East River, the loan to be covered by the tolls charged.

If this is not enough, then it will probably be necessary also to use government credit on useful public works which are not revenueproducing. This is the broad principle of the LaFollette and Wagner bills. It is, it seems to me, a remedy which could not have been resorted to at all until the financial measures I have outlined above had been taken. Adopted last autumn it would simply have strained the federal credit and deepened the deflation. The situation is different today, and the only reasons for hesitating about the adoption of an unproductive public works program on a large scale are, first, that if it can be avoided, we shall escape the creation of a great mass of new dead-weight debt for the future, second, that we shall not aggravate the evil of the pork barrel and of local extravagance, and third, that if all the other measures can be taken, it may not be necessary. By the time this article is published we shall begin to know. But the time is distinctly at hand when this remedy must be counted among the live possibilities.

Such a program of credit expansion can only be successfully carried out by countries with a large amount of surplus gold. For since mankind is devoted to the idea of gold it will not accept an expansion of credit which is not convertible into gold. It would flee from the deliberate expansion of paper money. This means that the policy of raising prices deliberately can be undertaken only by the two great gold countries, France and the United States. They alone have the means to do it. To make the policy a success they ought to do it jointly. But as I write the United States has decided to do it alone, for France, which is deeply orthodox in these matters, is not converted. By the time this article is published we may begin to know whether the daring American experiment is proving successful. If it shows any signs of working we may suppose that the French will modify their objections and cooperate. If they do, there is a chance that the vicious spiral will be slowed down and then stopped.

It would, however, be a great mistake to expect too much from the one measure alone. The structure of the world is so badly shaken in its vital parts that it is necessary to do other things simultaneously. For in addition to I his vicious spiral of deflation which I have been describing, there are at least three other spirals of disorder which have also become thoroughly vicious. It is necessary to intervene deliberately in each of them if the whole crisis is to be surmounted.

Continued on page 69

Continued from page 44

The first of these we may call the vicious spiral of trade destruction. This spiral originated in the debtor countries. When these countries found that they could no longer borrow abroad they had to choose between buying less abroad and ceasing to pay their debts. They have one and all chosen to cut down their imports and to push up their exports in order to have a surplus to meet their debts. But as each debtor country raised its tariffs and resorted to dumping, the other countries have raised their tariffs to stop the dumping. This in turn has forced the debtors to shut down still further on imports. This is clearly a vicious spiral which left to itself can end only with the destruction of all international trade and default on most international debts.

The break-up of this spiral must come either by the resumption of foreign financing or by the reduction of trade barriers or by both. There is little prospect in the present phase of public distrust that private lending will soon be resumed on an adequate scale. Therefore, it will undoubtedly be necessary to compromise with many debtors and also to relieve them by various kinds of internationally guaranteed loans. It is still more important to reduce the barriers to trade, and, although the political obstacles are enormous, a xvay must somehow be found.

Another vicious spiral which has to be taken into account is in progress in the realm of government. The shrinkage of profits and of employment puts a very great strain upon government finance. For unprofitable business reduces the yield of taxes and unemployment increases the need for expenditures. The result is that budgets everywhere are out of balance, and everywhere governments are in a dilemma. If they raise taxes to cover their deficits they add new burdens to business already overburdened with fixed charges. Thus they force business to economize, that is to deflate, which means that they force it to reduce wages or to discharge men. If, on the other hand, the governments seek to cover the deficit by reducing expenditures they themselves become deflationary: for they can retrench only by paying smaller salaries and by curtailing their own purchases. If they try to avoid the dilemma by borrowing, they depreciate their own credit, and since government bonds constitute one of the great pillars of private credit, the net result of extensive borrowing on an unbalanced budget is to aggravate the contraction of credit and the general deflation.

There are thus three choices open each of which has grave disadvantages. The struggle over which is to be adopted produces great political disturbance. If the government seeks to impose new taxes, there is a quarrel as to who shall pay them. If it seeks to retrench, there is stubborn resistance by the victims. If it seeks to borrow, there is hysterical alarm on the part of the creditor classes. There is literally no solution which is not burdensome and dangerous. There is no solution which is ideally just and actually effective. The effort to find a solution is, therefore, a supreme test of the national morale.

The problem is to find a solution which in some rough way preserves national unity. For in the last analysis the sense of unity alone is a powerful enough emotion to nerve a people to endure and to proceed. If the conflict is allowed to degenerate into a partisan and doctrinaire struggle about theoretical principles, the problem is insoluble. It can produce only confusion and paralysis. Therefore, for this effort nations have to evoke the instinctive patriotism which actuates them only in moments of overwhelming danger.

Finally, it is necessary to note the vicious spiral which has been set going in international relations. Although the crisis is obviously worldwide, and although, therefore, it most particularly calls for a spirit of international cooperation, it has everywhere accentuated nationalism, isolationism, and bad feeling. These separatist tendencies aggravate themselves. Nationalism in one country breeds nationalism across the frontier. The Hitlers stimulate the FranklinBouillons and the Ilearsts stimulate the Beaverbrooks. The great haters, the great fomenters of distrust, evoke the hatreds which then justify distrust. Hitlerism is nourished by French reaction and Messrs. Hearst and Beaverbrook furnish each other with the bitter ideas which each can then quote from the other. The international tension increases because it increases; nations hate because they are hated and are hated because they hate.

This daily poisoning of the wells of civilized life is done in the name of patriotism, under the aegis of the liberty of the press. There will come a time when the peoples will look upon such propaganda of hatred as treason to the human race. They will no more think it is patriotism than they now think that a swindle is productive labor.

It is time for liberal men to fight in the defense of those ordered ways of living on which all liberty and tolerance depend. It is time to talk bitterly to these bitter men and to confront them and to stop them in a spirit as determined, and, if necessary, as ruthless as their own. Too much is at stake to be tolerant of their intolerance. Nor need we fear that the people will not follow if a standard is raised to which they can repair. They turn to the apostles of hatred, not because their spirit is corrupt, but because hate is a simple passion and a strong one. They would prefer to be decent. They would prefer the prospect of peace and ease among men. They will listen to those who are working for peace when they see that the strong virtues, and not merely the amiable ones, are on the side of the angels.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now