Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Theatre1

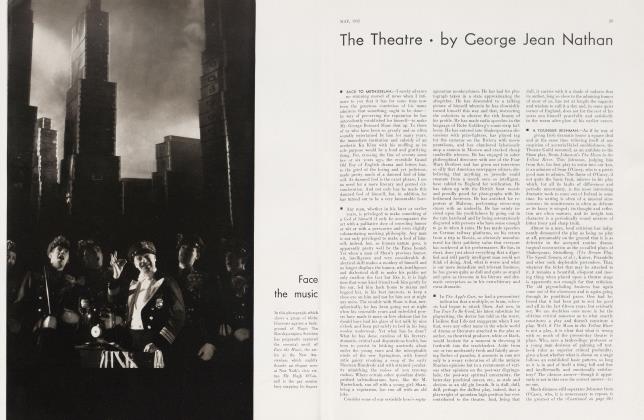

George Jean Nathan

■ SURPRISE PARTY.—For some time now, as readers of these dissertations are aware, it lias been my conviction that my English critical colleagues, undeniably talented and handsome though a number of them are, have become somewhat spoony in the appraisal of the English plays that they are called upon to review. Freely allowing for critical differences of opinion, we have nevertheless often found that exhibits which they have enthusiastically endorsed have been the seediest sort of gimcracks, and unaccountable of endorsement or enthusiasm even had they been written by their mothers, wives or best girls. Critical difference of opinion has had nothing to do with the matter; the plays were very had plays and there was an end to it; it was simply unbelievable that any critic, proficient or not, could manage to detect the slightest merit in them. The business could not be put down to log-rolling, for there is very little of that kind of thing among the English dramatic critics. They are, indeed, often more honest in the case of their friends—witness their frequent artillery in the direction of Shaw, to single out one instance—than in the case of complete strangers. Nor can it he put down to ignorance, for among the boys over there there is a full quota highly intelligent and very sharp-witted. Confronted in this juncture, therefore, by a loud call for the exact reason for their delinquency, I find myself taking refuge in the safe, if quite entirely unsatisfactory, answer that I'll he damned if I know.

• Only the very young or the very old dramatic critic is absolutely positive on all matters pertaining to the theatre. Each, when he beneficently endows his customers with an opinion, nails the flag to the mast and then seats himself with a triumphant and majestic certainty atop the pole. The critic of middle years, on the other hand, occasionally finds himself (much to his secret displeasure and annoyance) infected with duhitations, some of them of such refractory magnetism that they at least momentarily pull him from his complacent anchor. The English critic, whatever his years, generally gives one the impression of being in either the very young or very old critical catalogue, or simultaneously in both. There is an air of perfect finality to his decisions that permits of no shadow of doubt. He makes up not only his own mind, hut everybody's else, and—for all his often urbane phraseology—with some insistence. We Americans are supposed to he over-awed and, say what you more patriotic bounders will, it is a regrettable fact that many are. For, after all. in any field, a defiant and confident positiveness usually exercises its effect upon others. A wily newsboy in a quiet side-street yelling out a bogus sensational extra is always sure of a considerable number of customers. The quiet-voiced and timid critic, though he possess thrice the knowledge of his brassy brother, is lost in the shuffle. Criticism, above every other craft in the modern world, save alone politics and commercial theology, is a matter of steadily loud assurance. Much of American dramatic criticism, unlike some of that in England, enjoys the steady loudness, hut it lacks the necessary underlying assurance, or at least the convincing air of assurance.

■ In the last few years, as has been remarked, we have observed the forthright endorsement, on the part of English critics, of many plays that, subsequently appraised at first hand, have given us what may delicately be described as pause. I will not pain you with a comprehensive list, hut will content myself with pointing to a pretty brace: Ronald Mackenzie's Musical Chairs and James Bridie's The Anatomist. Both—the former in particular—were announced by our transAtlantic confreres to be what the English fondly believe all Americans are in the habit of alluding to as the cat's whiskers. And both, upon being studied in the flesh, were seen to he the most obvious kind of dramatic mummery. Here, once again, let it be noted that the matter is not a mere case of difference of opinion. There could or can he no difference of opinion, if the opinion is grounded in any way upon rational dramatic criticism. There may be a difference of opinion founded upon difference in taste, difference in personal prejudice or difference in experience, hut not upon intrinsic dramatic merit. One and one make two in sound dramatic criticism no less than in mathematics. And as time has gone on and as a succession of such meritless plays have been peculiarly hymned as relative trumps, it has been but natural that the old American grain of salt has come to resemble the Kalabagh.

All of which should, in the logical course of events, constitute a very tasty preamble to a review of still another highly touted English play recently disclosed to American audiences. But all of which—unfortunately for those of us who like to see their convictions and arguments come out as they wish them to— doesn't. For the play in point, Mr. J. B. Priestley's Dangerous Corner, lovingly admired by the English critics, turns out to be exactly what they said it was: a well-written, intelligent, discerning and sometimes even piercing study of human motive, impulse, conduct and reflection. Its basic fabric, true enough, is—as with most plays—woven out of one of the familiar platitudes, in this case, the disturbing consequences of truth-telling. In addition, the author has tagged a suspiciously box-office happy ending on to the tail of his play. But out of the aforesaid platitude, out even of his superficially haopy coda, he has fashioned a curiously provocative and

oddly insinuating slice of drama. Each turn of character, each motivating thought, and each deduction from thought and act is logical, shrewdly understanding and convincing.

I note various objections to the play on the part of some of its local critics. One is to the effect that the play, so the objection goes, is "talky", that it substitutes words for what is called action. But it seems to me that in Priestley's words there is infinitely more dramatic action than in most of the physical movement we see on the current stage. The idea that there cannot be action—and very definite, concrete action—in words is part and parcel of the equipment of amateur dramatic criticism. Which, for example, has more quivering dramatic and theatrical movement: the single wordy lament of the mother in Riders to the Sea or the -whole of the melodramatic The Silver King, Caesar's soliloquy before the Sphinx in Shaw's Caesar and Cleopatra or the physical movement in other parts of the same play, the speeches of Synge's Christy or his acts, the loquacity of Chekhov's Constantine or the dramatic manoeuvering of the other characters? Fine drama is born, first and last, of words, true words, vital and burning words, beautiful words. And there cannot be too many of them. Claptrap is the child of characters whose articulateness reposes chiefly in their legs and fists. The great dramatist is, above everything else, an eloquent talker. The hack is one who believes that human beings are only interesting and exciting when they aren't sitting quietly in a chair. (Hence, the moving pictures.)

m Another observed criticism of Mr. Priestley's play as drama is that—I quote—"it insists upon talking about things that never take place upon the stage" and that, furthermore, "its dominating character is kept in the wings and is never seen by the audience". The very adjective dominating, employed by the objecting critic, provides him with his own answer. If a playwright can keep a character off stage and yet have him dominate the play and the action, he assuredly is not open to criticism. He has set himself a feat and he has negotiated it. His play may not be a good play, but the mere fact that the audience is not permitted to see his "dominating" character does not necessarily lessen the audience's interest. The fact that the audience does not see the dominating character (Napoleon) in The Duchess of Elba, or the dominating character (Lambertier) in JeanJacques Bernard's Monsieur Lambertier. or the dominating woman character in Susan Glaspell's Bernice, or the dominating character (Christ) in Ben liar—to cite hut a few examples that occur to the immediate memory— surely hasn't diminished any audience member's interest in those plays. And the same thing holds true of certain unseen dominating figures in such plays as Maeterlinck's Intruder, Dunsany's Gods of the Mountain, etc.

Continued on page 53

(Continued from page 21)

But let us look into the complaints a bit further. To argue that a play insists upon talking about things that never take place upon the stage is not to argue satisfactorily that the play is therefore deficient as theatrical drama. Shaw's celebrated criticism of Sardou that he was in the habit of keeping his action carefully off stage and merely having it announced by letters and telegrams could not. for all its truth, persuade tens of thousands of theatregoers all over the world that Sardou's plays weren't literally bursting with theatrical drama. Sardou, true enough, was merely a very proficient hack and so perhaps is not the choicest specimen to haul into the present question. But there have been any number of superior playwrights who have equally insisted upon talking about things that never take place upon the stage and who have contrived some very good plays none the less. Shaw himself, while he cleverly pretends to be talking about things that take place upon the stage and shrewdly tricks his audiences and critics into believing it. more often actually talks about things that are taking place only—and a considerable distance away—in Downing Street, the Houses Parliament, the Fabian Society's meeting hall and the notebooks of Samuel Butler. Ibsen, in Little Eyolf, Echegaray in The Great Galeoto, and -peculiarly relevant to the present critical comparison—Her* vieu in The Enigma all talk more or less about things that do not take place upon the stage and nevertheless come off satisfactorily enough. 1 do not, plainly, mean to imply that Mr. Priestley is in any such select company, as yet. hut at any rate he isn't, as his objecting critics mean to imply in turn, in the company of the Vicki Baums and others such whose plays, like the strippers in the burlesque halls, think that, to hold an audience, they have to show the audience everything up to and including the fig-leaf.

THE DEVAL AND THE DEEP BLUE SEA.

—There is no news in the fact that French plays often suffer an attack of adaptational mat de mer when they come across the Atlantic and, accordingly, it will surprise no one that Jacques Deval's Mademoiselle is not quite so dramatically healthy in the version recently disclosed here as it was on its native soil. This local version, prepared and played by Miss Grace George, is, true enough, considerably more faithful to the original than is usually the case but, nevertheless, things have happened to it. Even were a spectator unfamiliar with the virginal manuscript, he would he more or less conscious that changes had been made in it. for there would persist in him a peculiar sense that something, even if he didn't know just what it was, was a bit wrong somewhere.

This wrongness, lie would eventually deduce, lies in the character of the governess as edited in the American version. In the original, the character in question is a woman ridden by bitterness toward mankind. Consistently, undeviatingly, at least throughout the first two acts of the play, her hatred of men, who have cheated her of her every inner desire, and of women, who have had what she cannot have and who, even as periodically she has been drawn to them, have permitted men to take them from her watchfulness and care, controls her every thought, feeling and act. The whole point of Deval's play rests upon this. Yet this hatred and this bitterness, in the American treatment, have been attenuated and sentimentalized in the nonsensical effort to make the star actress' role somewhat more sympathetic to the local popular audience. That it may he a successful box-office dodge, 1 haven't a doubt. But that it goes a long way toward ruining the integrity of Deval's script is equally certain.

The play itself is a so-so comedy, though superior to a number that have been imported from France in recent seasons. That very relative shade of superiority seems to me to have merited a little consideration and protection. Certainly when the best moment in the play is sacrificed by a timorous adapter and leading woman to boxoffice sentimentality, the author has a right to complain, that is, if he has a pride that cannot be salved by mere box-office returns. The moment in question provides the curtain to the second act. In the original, the acrimony of the governess is brought to the boiling point when her young charge—who confides to her that she has, albeit illicitly, come by the one thing in all the world that the governess has dreamed of for herself, a baby—tenderly kisses her cheek. In a poison of rebellion and hatred the governess slaps her hand to her face and viciously wipes the kiss away. In that moment, the character of the woman is brought brilliantly to completeness. But what happens to Deval's governess over here? When the young girl kisses her, she gazes tenderly after her as she leaves the room, permits a hokum look of incipient motherlove to illuminate her features, and wistfully touches the place on her cheek where the buss was imprinted. In the words of Mr. Bert Lahr, now I ask you!

BLACKOUTS AND INTERMISSIONS.

—The eminent Bernard's remark that more theatregoers are bored by intermissions than ever were bored by plays applies as well to internal intermissions in plays. Nothing so lets an audience down as the customary actintermissions. What success the moving pictures have enjoyed is doubtless at least partly due to the fact that they have done away with intermissions, play right through from begining to end. and so sustain their audiences' mood and interest. But not only has the dramatic theatre persisted in its idiotic and ruinous custom of intermissions after each act of a play; it has, to boot, lately often increased the hazard of such intermissions by a long series of brief intermissions within each act of a play. I allude to the multiplying number of plays whose acts consist of many short scenes and which, to effect the necessary changes of scenes, intermittently either douse the lights or drop the curtain for a period of anything from one to two or three minutes. To demand of an audience that its mood be preserved in such circumstances is to demand the impossible. More plays have been killed by blackouts, frequently dropping curtains and intermissions than have been killed by all the destructive criticism since the theatre began.

(Continued on page 61)

(Continued from page 53)

Take, for example, a play called Carry Nation, by one McGrath, not long ago offered to the local trade. It was, in good truth, a poor attempt at chronicle drama setting forth the life and times of the illustrious saloon butcher. But had it been a ten times better play, its two minute blackouts between each of its fifteen scenes, to say nothing of two fifteen-minute intermissions added at due intervals for extra measure, would have knocked out completely the audience's interest. Intermissions may be well and good for trashy plays—the longer then, the better—but in the case of worthier plays they are simply the refuge of audience ignoramuses. Revolving stages and other such modern devices can handily do away with the old mechanical necessity for them. And the human rear which is competent to sit patiently and ungrumbling at a two-hour dinner party, a three-hour heer table or in a four-hour Pullman chair is perfectly competent to sit patiently ungrumbling in a two-hour theatre seat.

VARIOUS OTHERS.—The Late Christopher Bean was credited on the programme to Rene Fauchois and Sidney Howard, but what credit there was should have been listed in the name of the M. Gilbert Miller. It was the latter's adroit casting, staging and direction that gave the exhibit any interest the audience might have found in it.

Autumn Crocus, by an Englishwoman named Dodie, I reviewed in these pages a year or so ago after a view of it in its London presentation. As 1 noted then, it is an excessively soupy affair, quite without quality, which gains what theatrical life it has from the performance of its central male role by Francis Lederer, formerly leading man to the German actress, Elizabeth Bergner. Music in the Air provides another highly pleasant evening with a Jerome Kern score. I commend it to the attention of your music-show starved ear. It would be a delight in any season, and it is a double delight in this.

In the next issue: A S+eichen portrait of Pauline Lord

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now