Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

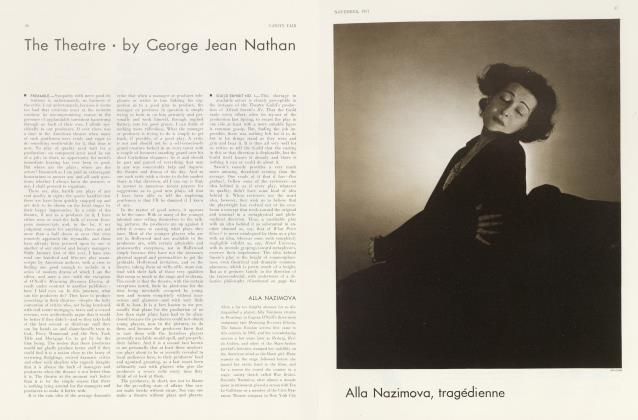

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Theatre

George Jean Nathan

WOLF INTO SHEEP.—Those good old-time theatrical managers whose predilection it was to allege that had notices of their plays were entirely due to the fact that the critics were victims of dyspepsia— and who themselves, alas, all died of it (with diabetic complications)—would, were they to return to earth today, he dumbfounded at the change that has come over things. I do not go so far as to contend that the critics have been converted into so many mushballs, dripping great gobs of crème Yvette over any and everything that comes along. That would be far from true. But it is certainly true that if Charlie Frohman, Ahe Erlanger, Marc Klaw, old man Liebler, Henry Savage and other such producers of yesterday were with us now, they would rub their eyes in bewilderment over the enthusiastic critical endorsement of many a play about which they themselves, dyspepsia and diabetes or no dyspepsia and diabetes, would very probably have private and very positive—perhaps even intelligent —-critical misgivings.

Even at this relatively early period of the season we have already observed a number of plays, at best deserving of faint praise, touted by the critical gentry as something eminently and magnificently lush. To believe that there was anything in the least dishonest or hypocritical in the appraisals is to be grievously mistaken, for, by and large, the present-day reviewer is a sincere, upright and wholly unprejudiced fellow—

a very different one from his brother of fifteen and twenty years ago. I desire to emphasize the point, since the deduction 1 wish to make from it might otherwise he taken by some to be a reflection upon the local critical probity. The deduction is as follows.

While the overly enthusiastic reviews that are presently being accorded certain very dubious plays are in themselves completely honest and the scrupulous and undissembling refraction of their sponsors' critical convictions, there undoubtedly yet remains a reason behind the reason for them. That reason is an understandable one, and is twofold. For some time now, the professional theatrical critics have been made to feel—and have felt—that, unless something was done about it pretty soon, the theatre, which is their source of livelihood (plus beer), would die of celluloid poisoning.

Massaging themselves into the plerophory that there must he something in the cocksure statements of the various movie executives (themselves all in the bankruptcy courts) that the movies were rapidly driving the theatre into the discard; alarmedly reading the published affidavits of the larger movie cathedrals that they were playing to a gross of sixty and seventy thousand dollars weekly (showing a net weekly loss on investment of twenty thousand); giving a trusting ear to the pronunciamentos of various producers (who had lost all their money in the stock market 1 that the theatre was too dangerous an institution longer to risk their money in—the critics very truthfully, if very innocently, began to believe that they were part and parcel of the situation's salvation. It was not always a consciously arrived at belief—far from it— hut, consciously or unconsciously, it was, down in their innards, a belief none the less.

Like an absinthe drip in a summer's twilight, the conviction gradually permeated their very souls, and a kind of boozy goodwill, a hot wish to believe, a species of critical rosiness began to steal over them. "We'll show those movies where they get off!" sounded, subconsciously, the little whispering voice within them. "We ll tell the world the theatre is a long way from being dead, or even sick!" repeated the little hidden voice. And so, almost without their realizing it, there was born in them a critical philanthropy of such proportions that, were they soberly and surgically to meditate it, they themselves would he the

first just a little aghast and struck all of a heap to perceive it.

In addition and here, at least, I am one of their number—they have observed with a sinking of the heart such an endless procession, in the last three or four years, of impossibly bad plays that, if the theatre wasn't dying, it seemed up to someone mercifully to put arsenic in its soup and see to it that it did kick the bucket. But while there is life, there is hope—and out of the impulse described above there came a second impulse—came as logically and naturally, after a long absence, as a boy's kiss to his mother: the impulse, to wit, to praise not merely where praise was fairly due, hut to praise on tin* basis of purely relative values. Five bad plays, ten bad plays—and then a passable one. And the merely passable one was seen in the comparative light of a masterpiece. And not only seen, hut so recorded, with the qualifying comparative somehow omitted.

As a consequence of the present general critical attitude, we behold the phenomenon of very ordinary plays ecstatically greeted as plays very close to perfection. All of which is grand for the prosperity of the theatre, if just a little confusing to the art of Sareey, Sehlegel and Hannan Swaffer.

EXAMPLES.— Double Door, by Miss Elizabeth McEadden, is, to he sure, a better play than any of the exhibits that had preceded it in the early stages of the season, hut it is at the same time a very bad play. It simply happens to he not so bad as the others, which were plain godawful. Men in White, by Sidney Kingsley, is a much better play—a very much better play—than Double Door, hut it is at the same time far from being a soundly good one. The critical fraternity, with slight exception succumbing to the comparative critical liquors herein indicated, got out the brass hand for Double Door and, then, the liquors warming up their tum-tums, added a fife and drum corps to the band when it came to Men in While. And when the farce-comedy Sailor. Beware! by the MM. Nicholson and Robinson, shortly thereafter heaved into view with half a dozen good laughs in it, a new Commedia dell' Arte was born, if you were to believe the newspapers, on the spot, You see, there had been only about one or two laughs of an evening to be found anywhere, and six came close to constituting just about (Continued on following page) the richest and gayest farce-comedy that had ever been seen in this world.

Danger lies in such a critical disposition. For it is ever a way with criticism to support its individual position by persistently asserting the verity of its initial opinion and never admitting that there may have been a flaw in it. Successful criticism is the convincing reiteration of beliefs that may often he dubious. It thus comes about that what was initially merely a relative judgment, combined with the sudden excitement that theatrically follows a long period of enforced mental and emotional starvation, is gradually transformed, by way of a defense mechanism, a critical protective coloration, or maybe a kind of personal vanity, into part of a body of critical doctrine. Or, in any event, into something that the critic himself persuades himself is a forthright and sound conclusion. . . . Critical praise unjustified is bread cast upon the waters; it returns to the critic in time as an embarrassing and corrupting whole delicatessen store.

It is the furious wish and will to have plays good that is currently playing havoc with sound critical standards. And not oidy lo have plays good—in these days of the theatre's doubts and alarms—but to have the players good. We are thus entertained, as I have noted, by a third-rate melodrama like Double Door hailed as first-rate stuff simply because it isn't sixth-rate and, to boot, is acted on an ominously darkened stage and directed as if it had been written by Calvin Coolidge. We thus hear extolled as very fine dramatic art a play like Men in White which, while not without dignity of intention and one or two effective theatrical scenes, is little more than second-rate Brieux. We thus observe a crude, if periodically amusing, little farce-comedy like Sailor, Beware! stampeded into a box-office rodeo, for all the world as if the combined comic genius of Goldoni, Moliere and Mayor O'Brien had gone into it. And, in the quarter of histrionism, we behold that fine singer hut laughably inferior actor, that colored Johnny Weissmuller, that licorice Walter Hampden, Mr. Paul Robeson, garlanded with blooms as a bigger and better Salvini, while out of the corner of another eye we discern that nice little girl. Miss Francesca Bruning, critically panegyrized as the heavenly feminine and wistfully nostalgic ghostess of Mary Anderson. Maude Adams and Bonnie Maginn simply because, in Amourette, she had on an oldfashioned long soft white ruffled petticoat.

■ CRITICISM GOES DEMOCRATIC.— But let

us not grouse too much. There is sweeter critical news on tap. I allude to the present attitude toward musical shows. There was a day, and not so very long ago, when any musical show', however excellent, was looked down upon as something just a bit critically undignified, and worthy only of the attention of the second-string reviewer, the first-string professor dedicating his career rather to the genuine art works of Charles Klein and Eugene Walter. All such nonsense is now fortunately a thing of the past, safely buried in the grave along with William Winter, J. Ranken Towse and the Columbia University hazlitts (excepting Brander Matthews, who had sense enough to appreciate that one girl's beautiful leg was worth all the plays that Alfred Sutro ever wrote, particularly when it was lifted into the air).

The first-rate musical show' no longer is denied its critical due. And why should it be? Not a single play produced up to the evening of the Moss Hart-Berlin revue, As Thousands Cheer, had in it one-third the theatrical—even comedy-dramatic—skill that that show had. It had greater originality fin the best sense) ; its humor was sounder and louder and funnier; its taste was better; even its share of intelligence was infinitely greater. It deserved, and thoroughly, all the critical whoops that were accorded it. I herewith add my modest

Undoubtedly Of Thee I Sing provided criticism with its biggest push in the right direction, although there were several exhibits before it that helped to grease the ways. The music show at its best was seen to be something not to be airily sniffed at. It was seen to be a fine funnel for the native humor, for some of the better satire,

for a kind of visual beauty that is not often achievable on the dramatic stage. It was seen, indeed—as some of us had seen it some years before—to be, perhaps, by and large the most distinguished American contribution to the modern world stage.

As Thousands Cheer, admirably participated in by Clifton Webb and the Miles. Marilyn Miller and Helen Broderick, is something more than a mere revue, that is, a revue as we have come to understand and accept the term. It contains, of course, the expected girls, tunes and other such customary ingredients of the revue, but it has, in addition, a very real satirical, dramatic essence. Each and every one of its skits and sketches has, under its fun, a tonic critical commentary. I have often in the past referred to the Frenchman who signs himself Rip and whose revues have been for many years the life of the Parisian theatre. In As Thousands Cheer, the hitherto matchless Rip has found a rival. This Moss Hart is a hoy worth keeping our eyes on.

Hold Your Horses, another musical show of which much was expected, turned out to be pretty dreary stuff. But one doubts that the fault lay with the MM. Corey Ford and Russel Crouse, who had in other directions already proved themselves to be sufficiently amusing fellows. That alien hands—and very heavy ones—monkeyed with their book is all too obvious.

FURTHER EXHIBITS.—The local critical benevolence, mentioned in the opening paragraphs of this dissertation, came again to rich (lower in the instance of The Pursuit of Happiness, by Alan Child and Isabelle Loudon (Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence Langner), produced by Laurence Rivers (Rowland Stebbins), and acted by a company including Dennie Moore (Mathilda Langner), Charles Waldron (Herman Langner), Peggy Conklin (Prunella Stebbins), Tonio Selwart (Tewksbury Lederer Langner), Raymond Walburn (Henry G. Langner) and a Negro player, Oscar Polk (George Jean Nathan, Jr.). Having hit upon the old Revolutionary period custom of bundling as a saucy comedy idea, the authors achieved the mistake of believing that the idea was good for a whole three-act play, whereas in all practical likelihood it is good for merely a single situation. To contrive out of it a full-length play would call for either a robust humor or a sly wit, neither of which the present authors seem to command. The result is about fifteen minutes of fairly sprightly fun in the second act and an endless and rather tedious lot of preparation fore and decoding aft. But just the same, so pervasive is the current reviewing charity that the play got such gala notices as most of us will get only upon our deaths.

(Continued from page 42)

What humor (aside from that implicit in the bundling episode alluded to) the playwrights manage to negotiate consists mainly in a foreigner's difficulty in grasping the shades of English meaning, with the consequent theoretically risible results. As, for example, when the young foreigner desires to tell his inamorata that he wishes to spark with her, he blurts out, "Tonight I will come and we will make sparks." I am afraid that I stopped laughing at that kind of thing in 1894.

All the reviewing benevolence and good will in the world, however, couldn't possibly persuade itself to do anything about Her Man of Wax. This was the sour Broadway gimcrack derived from Walter Hasenclever's Napoleon Intervenes, a play not without some pointed satire and humorous interest. Poor Hasenclever got a dirty deal from his local producer, including an adaptation that adapted out of the original nine-tenths of its portion of merit, a stage director who imparted the impression that his last previous vocation was the directing of freight traffic at some hinterland railway junction, and, last but not least, Miss Lenore Ulric. All that the adaptation and the director didn't do to Hasenclever, Miss Ulric did. Clad in snaky black and white satin gowns that lent her the appearance of a lascivious cervelatwurst, she coiled herself around the manuscript with so assiduous an imitation of an irrepressible hot mama that Theda Bara, recalling her long-ago screen activities,

would have blushed scarlet for her own gross iciness.

In place of Hasenclever's rather intelligent and nicely barbed script, what we got on the stage of the local theatre was little more than a dinky paraphrase of the If Christ Came to Chicago sort of junk (popular thirty years ago), with the central figure dressed up as Napoleon and set down in present-day Paris. The so-called humor had to do with Napoleon's perplexity over such modern contrivances as the radio, the telephone and the shower bath, and most of the rest of the evening was devoted to the aforementioned Miss Ulric's passionate efforts to make the hero delete the not from the famous nocturnal injunction to Josephine commonly attributed to him in American smoking cars. Mr. Lloyd Corrigan's sole recognizable histrionic endowment for the role of Napoleon seemed to be a rotund little belly, though even that may have been a small sofa pillow rather than a naturally inherited or genuine achievement. The rest of the company, hired to play such French characters as General Louis l'Oiseaux, General Du Marais, General Courot, Le Brun, Senator Buvette, et al., comported themselves like German spies.

Die Fledermatis was lately with us again under the alias. Champagne, Sec. Old Johann's music, of course, provided all the happiness that it always does, but the book, despite the various tricks of adaptation that were visited upon it, remained something pretty dreadful. An attempt was made to inject into it what gayety it lacked by causing the leading performers and the members of the chorus to issue uproarious laughs after each spoken line and at the conclusion of each of the musical numbers. The result of this humor kleptomania was only to depress the audience doubly.

The School For Husbands, adapted from Molière's L'Ecole des Maris by the Messrs. Guiterman and Langner, with a musical accompaniment by Edmond W. Rickett, was the Theatre Guild's second production of the season. Accorded a flattering critical press, it opened, unfortunately, on a night when your reviewer was suffering from a cold the like of which had never before been recorded in medical history and which so numbed his critical faculties that anything he might write about the exhibit would not be worth printing or reading. He therefore bespeaks your indulgence until he gets around to the performance again on some future and more healthful evening.

Ten Minute Alibi, an English importation by one Armstrong, is a mystery piece rather more interesting than the general run of such things.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now