Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

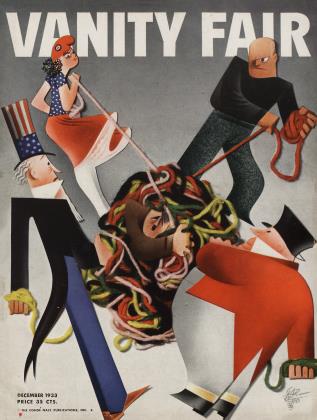

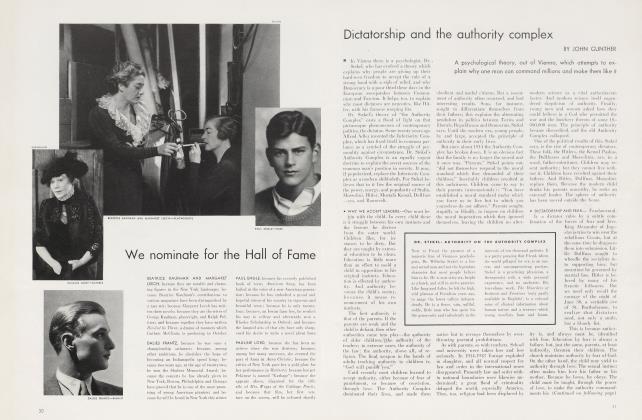

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowChancellor Dollfuss: flyweight champion of Europe

JOHN GUNTHER

■ Not to every man in public life is it given to be four feet eleven inches tall. These lucky ones find merit in the worm's eye view. They don't have to hurdle obstacles; they squeeze through them. Lacking hulk, they learn shrewdness and tenacity. They are conspicuous because of their very inconspicuousness—like Dr. Engelbert Dollfuss, the midget chancellor, the milli-metternich of Austria. The most popular dictator in Europe, as well as the youngest and smallest, his recent miraculous escape from an assassin's bullets made him the world's news-reel hero and evoked unprecedented expressions of sympathy, even from the government of his severest, to put it mildly, critic, Hitler.

Dollfuss' luck at all times has been of phenomenal quality, hut on October third, at 2:15 p.m., occurred the luckiest thing that has happened to him yet: he was shot. At 2:14, he was only a chancellor. At 2:16, he became a martyr, and what's more, a living martyr. Only his good luck stood between his heart and two bullet shots fired at less than two metres away. But it was his intuitive political genius that made him deliver a radio speech from his bedside that made him the world's pet convalescent. A literal deluge of telegrams, flowers, gifts, poured in from every curve of the universe. The would-be assassin turned out to he a

slightly van-der-loony Nazi. How Hitler must have wanted to choke him for having made a hero out of his worst enemy!

Little Dollfuss is the only man on earth so far who has made a monkey out of Hitler. Running 6,000,000 people, he has made Germany, with 60.000.000, eat dirt. Like David, he exasperates and infuriates the clumsy, powerful German Goliath. Like a wasp in an elephant's ear, he sings his penetrating little song, and produces paroxysms of impotent fury in the slowmoving northern giant.

Vienna, an easy-going city, rather bored by politics, proud of taking nothing seriously, least of all itself, is taking Dr. Dollfuss very seriously indeed, and his fight against the Nazis. Dollfuss has dramatized himself into the heart of the Austrian nation. Partly because of his policies. But also because of his size. You can be angry

at a six-footer, but a prime minister barely five in his stocking feet is irresistible. Hitler is an ogre, Dollfuss a sort of mascot.

Already the legends about him pile up shoulder high. They combine the irreverence of Vienna, the affection, and the soft, seductive wit. It is being echoed—softly from the housetops—that a new issue of postage stamps is impending, with portraits of Dollfuss, life-size.

As tough as he is small, Dollfuss has been chancellor of Austria a year and a half. He was born in the hill country along the Danube in 1892. Thus he is the youngest prime minister in Europe as well as the smallest. His people are peasants. They have knotty hands like boulders. His mother works in the fields today, near the small farm where he was horn.

Dollfuss came to Vienna as a hoy and got a degree in law (Continued on page 62) at the University. Practically all Viennese who can read or write are doctors, and so his degree does not, necessarily, mean very much. He went to Berlin to study economics. The war came and he enlisted as a private and came out a lieutenant, rather a feat in those days, in the Imperial Austrian army. (A corporalship was the best Adolf Hitler got in Germany.) Dollfuss liked the land and returned to it, at least in spirit. He became an agrarian expert and presently, at a very tender age, the director of the Lower Austrian Chamber of Agriculture.

(Continued from page 25)

He got the chancellorship late in May, 1932. after an elaborate and confusing cabinet crisis; no other politician, so shaky wore Austria's finances, wanted the job; moreover no one else wanted to rule with a majority of exactly one, which was the best the government could muster in the chamber.

Dollfuss seemed just another stopgap chancellor, if abler and more amiable than most; an Austrian given, like all Austrians, inveterately to compromise; a nice young fellow whom the job would break. Then, in the north, came the enormous phenomenon of Hitlerism. And Dollfuss, like a marionette, was jerked upward into the spheres of history.

Hitlerism, he it understood, is not only a political movement but a religion. A top point in the Hitlerite dogma is Anschluss, i. e., union of Austria with Germany. Both sentiment and politics contribute to the German thesis that Austria is not Indy an independent nation hut merely a limb truncated from the body of tile Reich. And then the puny Dollfuss decided that Austria was not going to be swallowed whole.

He had to fight on two fronts, an external war and at the same time a civil war, so to speak. Externally there was an enormous incursion of north German propaganda to face, propaganda distributed by able agitators, hacked by men, money, arms. Internally be had to confront the fact that his people were, after all, Germans, and that among them was a very active pan-German spirit, stimulated toward fruition by the triumph of the Nazis. When Hitler reached the premiership in Berlin a mass-meeting of 20,000 Viennese rose to shout that he was their Chancellor too, not Dollfuss. But Dollfuss began to fight back.

First of all, the dying parliament, with his shaky majority of one, was a nuisance. He went to the President and threatened to resign unless he was given semi-dictatorial powers: he won.

(Continued on page 69)

(Continued from page 62)

Next, he crippled the strong Socialist opposition by dissolving the private Socialist army, the Schutzbund. Austria, having been forbidden any hut a nominal public army by the peace treaties, had built up two private ones. With the Schutzbund out of the way the arena was clear for the rival army, the Heimwehr, representative of the forces of clerical conservatism.

The Socialists, even with their army gone, made a pretty problem. Dollfuss announced that he was building a government strictly of the centrer, equally opposed to both National Socialist (Fascist) and Social Democrat (semi-Marxist) reaction. The Socialists do not like Doll fuss. But, unhappy devils, they have been maneuvered into a position literally between frying pan and fire. And so far at least they have endured mild broiling by Dollfuss in order to avoid complete incineration by the Nazis. Dollfuss, for good or ill, is their best—in fact only—defense against Hitler.

At first the Nazis were contemptuous of Dollfuss. The contempt changed to consternation and anger after May 1, 1933. On this date, Dollfuss called out the army and in effect dared Hitler

to do something.

Hitler, in Berlin, was furious. 11c sent Papen and Goring to Rome. Dollfuss hopped in a plane after them. Both the Germans and the little Austrian courted Mussolini feverishly, and Dollfuss won. All the cards, in this one episode, were in his favor, because Mussolini is no friend of Anschluss; he does not want strong Germans on the Brenner Pass and behind Trieste. He much prefers soft Austria as a buffer state.

Hitler then sent Dr. Frank, a Bavarian cabinet minister, to Austria, to explore this highly unexpected situation. Dollfuss, with amazing cheek, sent a policeman to the airport to welcome Frank with the statement that his visit was "not very desirable." Then, smart as a chickadee, he fixed it so that Frank and his companions were led through deserted side-streets to the Nazi headquarters in Vienna, while—perhaps by lucky coincidence —the Heimwehr staged an enormous parade on the Ring.

Those thousands who saw Dollfuss take the Heimwehr salute got the surprise of their lives. There was the little man, coming up to his aide-decamp's armpit, in the uniform, not of the Chancellor of the Austrian republic, but of the old imperial army. Dollfuss deliberately revived the timeworn, tattered, faded insignia of the Hapsburg. It gave the crowd an immense emotional throb. It made them believe again in Austria as Austria.

The cards were on the table now. It was obviously a fight to a finish. Austrians themselves shuddered at their pocket Napoleon's temerity. Dr. Frank began to grumble. With infinite politesse, Dollfuss threw him out of the country. The Nazis talked wildly of "invasion." This was exactly to Dollfuss hand. He used a scare story of an impending Putsch on the AustroBavarian frontier as pretext for banning brown shirts in Austria. For a

short time the frontier was closed.

The climax soon came. Nazi violence began to break out like eczema over Austria. Dollfuss retaliated with the final weapon: he outlawed the Nazi party. This was on June 19, 1933. The Germans retaliated. By imposing a thousand-mark fine on any German visiting Austria. By sending airplanes to drop anti-Dollfuss bomb-literature over Austrian territory. By beginning an anti-Dollfuss radio campaign.

The powers themselves then protested, France and Britain publicly, Mussolini privately. The Germans promised Mussolini they would stop. Mussolini told France and Britain that the Germans would stop. The Germans did not stop—quite. Mussolini's role of mediator-in-chief to Europe-at-large became just a tiny bit funny. A statesman can forgive anything except being made ridiculous, especially an Italian statesman. Mussolini hasn't forgotten that incident.

Moreover, in September, as good luck would have it, came the 250th anniversary of the freeing of Vienna from the Turks, combined with a great Catholic jubilee. Vienna swarmed with visitors and stirred with new vitality. Before a crowd of a hundred thousand on the race-course in the Prater, Chancellor Dollfuss announced that his new movement, the Vaterlaendische Front, would embrace all parties.

An interpretive fight on this speech, threatened to break up his cabinet. Dollfuss settled the fight by dissolving his cabinet and rebuilding it overnight. Vienna went to bed at ten one night in a republic, and woke up at ten next morning in a dictatorship. In the reorganized cabinet of eight members, Dollfuss took five portfolios, chancellory, foreign affairs, defense, public security, agriculture.

Immediately after this coup-de-cabinet, Dollfuss went to Geneva again, and speaking before a packed house that included the Nazi propagandist Goehbels, he got the biggest ovation the Assembly has ever given anybody since Briaiul blessed Locarno.

How long Dollfuss will last is, of course, problematical. He may get licked. His present clevernesses may seem very small a year from now. Ultimately 6,000,000 people may indeed have to succumb to the pressure of 60.000,000. And Dollfuss has to fight on many fronts. There is treason in his own party to watch; there are the powerful, obdurate Social Democrats who must be conciliated, if Austria is to survive decently; there are the international forces represented by France and Italy to control.

Dollfuss is the first Austrian statesman since the war to believe ruggedly in the independence of Austria. All other Austrian politicians were defeatists. They all—an amazing paradox—believed in the abolition of Austria! Dollfuss believes in Austria as Austria. Europe, be it said, has suffered deeply from the excesses of nationalism, and additional nationalism is not exactly what the world would seem to need; nevertheless, if Dollfuss can create an independent, stable, perpetually neutral Austria a la Switzerland, .he will, as the French say, have deserved well of his own republic.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now