Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe how and why of political assassination

JOHN GUNTHER

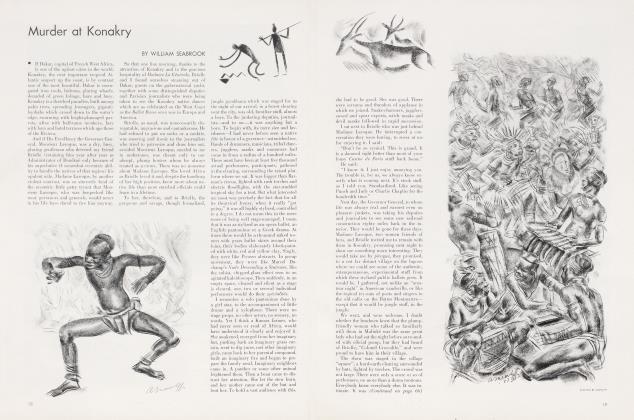

Two or three years ago, en route to Constantinople. I spent a few weeks in Sofia timidly exploring the ways of the macabre and murderous Macedonians. One of the chieftains who was kind to me was named Tomalevsky. He was a cultivated and intelligent man, probably with several murders on his head, and he arranged for me to go out into the hills and see at first hand the workings of the Macedonian movement. Some time later, in Vienna, 1 was shocked to learn that Tomalevsky had been shot— murdered at the same desk, in the same room, where I had seen him, a victim of intra-Macedonian vendetta.

The man who killed him, 1 heard, was Vlada Georgieff. It is quite possible that I met Georgieff in a Sofia café, or out in the frigid valleys of the Bulgar-Jugoslav frontier; I met dozens of revolutionary terrorists; I am not sure. The Georgieff who killed Tomalevsky was guilty, the police said, of some dozens of other "patriotic" murders, and he fled the country. An.exile, he became a complex and competent fanatic. He had two leading ideas: to blow up the League of Nations, and to murder King Alexander of Jugoslavia. He never got around to blowing up tin1 League. But Alexander met his death at Georgieff's Macedonian hands, on the streets of Marseilles, October 9, 1934.

Many and curious are the ways whereby a personage may leave life and enter history. Charlemagne died of pleurisy; Saint Lawrence was toasted on a grill; Nero killed himself. Catherine the Great died of apoplexy; Napoleon III from gallstones; Attila was murdered on his wedding night. File Roman Emperor Cams was killed by lightning, the English King Edwy, back in the Tenth Century, died of grief, and Charles V of Spain ate himself to death.

Almost all the great military chieftains of history, who sent millions to their deaths, died in bed: Frederick the Great, Napoleon, Alexander, Wellington, Charles Martel, Marlborough, Hindenburg, Tamerlane, and Genghis Khan. Exceptions were Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, who was killed in battle; Hannibal, who committed suicide rather than give himself up to victorious Rome; and Julius Caesar.

Christ was the only founder of a world religion who died a violent death. Buddha. Confucius, and Mohammed all died peacefully in bed, Buddha at the age of eighty, Confucius at seventy-three, Mohammed at sixty-two. The circumstances of the death of Moses are a mystery, but legend says he lived till eighty.

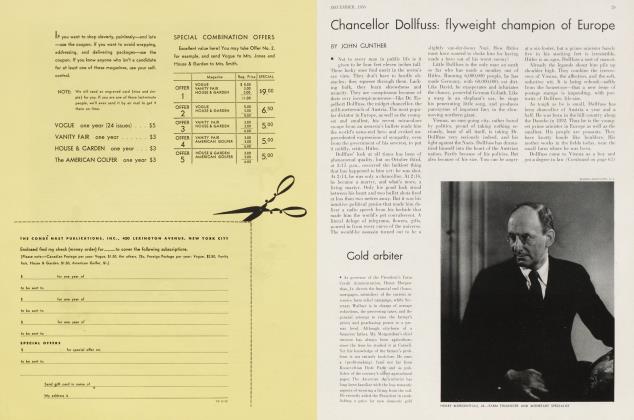

The carnival of political assassinations last year—Duca (Prime Minister of Roumania), Pieracki (Polish Minister of the Interior), General von Schleicher and his wife, Dollfuss, Alexander, Barthou, and Kirov—proves that murder has not lost favor as a political instrument. Politics is a dangerous profession. Very few great musicians, philosophers, novelists, engineers, millionaires, doctors, lawyers, or artists have ever been murdered. Among scientists, Archimedes is the only one I can think of; among poets, Kit Marlowe. But call to mind the gruesome scroll of kings, presidents, prime ministers.

• In the past seventy years three American Presidents have been assassinated; four Prime Ministers of Spain; two Presidents of France; two Japanese Prime Ministers; no fewer than nine Latin American Presidents. One Shah of Persia has been assassinated since 1865, one sultan of Turkey, one governor-general of India, one President of Poland, and kings of Serbia, Portugal, Greece, and Italy. The Empress Elizabeth of Austria-Hungary was assassinated; so was the great French socialist Jean Jaurès, so were Irish politicos like Kevin O'Higgins, Croats like Raditch, and Germans like Rathenau, Liebknecht, and Rosa Luxembourg.

It is an interesting fact that most of the great assassinations of history produced results opposite to those anticipated by the assassins. Julius Caesar was murdered to save the Roman Republic; but his death brought the Empire. Lincoln was killed by Booth, a fanatic Secessionist; Lincoln's death confirmed the integrity of the Union. Charlotte Corday murdered Marat in his bath to halt the bloody tide of the French Revolution; following his death came the Reign of Terror. The Nazis killed Dollfuss last year in order to seize power in Austria, hut the death of Dollfuss united Austria against the killers; the Nazis murdered their own campaign.

History is not a science, and there are exceptions to this rule. The murder of Matteotti, for instance, accomplished just what the Fascist assassins hoped for, the death of overt opposition to the Mussolini régime. Princip and his comrades killed the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in order to "liberate" Serbia; this they did, but only after four years of a somewhat extensive war. Catherine the Great ordered the murder of her husband, Peter III, and obtained thereby exactly what she wanted—security and power.

"Assassination," an odd word, comes from the same root as the Arabic for "hashish-eater, which is Hashshashin. And the first personage in history to make assassination an acknowledged and indeed exclusive instrument of foreign and domestic policy was a Shiite Persian named Hasan who formed the Sect of the Assassins in the Eleventh Century. He may or may not have been a hashish addict; his name contributes two syllables to the word "assassinate." Hasan ruled his capital Alamut by orderly and progressive secret murders; after a long and prosperous rule he died peacefully at an advanced age. But his descendants, son, father, son, poisoned one another with formidable and ingenious success, until the Turks came along and assassinated all the assassins who were left, some twenty thousand.

There is a precise common denominator of several of the political assassinations of 1934. They were performed by fanatics with the purpose of overthrowing or weakening the regime in power and opening the way for a government more representative of the common people. Filipescu, the assassin of Duca; Planetta, the murderer of Dollfuss; Georgieff, the killer of Alexander and Barthou, were all good democrats, even though one was an Iron Guardist, the second a Nazi, and the third a Macedonian. Their aim was identical—to remove a pillar of unpopular government so that the people might be "free."

Nikolaieff, the assassin of Kirov, is in a slightly different category; he murdered Stalin's friend because he thought the revolution was being betrayed; he was a communist who felt that Stalin, Kirov, and the Kremlin gang were throttling Communism General von Schleicher was a conspicuous victim of the June 30 Hitler "purge;" the Nazis wanted to kill all surviving German ex-chancellors, especially von Schleicher who was accused of intriguing against them; von Schleicher was the only one they got. His wife met her death because she was an inadvertent witness of the killing.

Continued on page 60

( Continued from page 20)

Sometimes the border-line between murder and assassination, between assassination and execution, is very difficult to draw, as in the case of Captain Boehm, the repellent Storm Troop leader who also met his end on what the Nazis persist in referring to as a weekend of good, clean fun. Boehm was supposed to be leading a BrownShirt revolt in Munich on 7 a.m. of the 30th. But Hitler found him in bed, with a comely Lustknabe, both drunk, at about four the same morning at Bad Wiessee, some forty miles away. He was arrested, brought to Munich, given a revolver, and told to shoot himself. He replied, "No one may shoot me except Adolf Hitler with his own hands." This was brave rhetoric, but it did him no good, because the firing squad killed him the next day.

What is the psychological basis of the desire to kill? We all of us are secret murderers; not many people could truthfully say that they have not, at one time in their lives, killed somebody—in their thoughts or dreams. Our secret victims are usually people quite close to us—employer, employee, son, wife, father, friend. Assassins are those who act upon an eruption of the subconscious, like a volcano. The idea to kill, to transform the dream to reality, comes like a bolt of lightning; it is irresistible, and murder is done.

Dr. Wilhelm Stekel, the great Yiennese psychiatrist, ihinks that most political murders are offshoots of a distorted father fixation. Cranks and anarchists, who seek out and kill statesmen to satisfy some mysterious personal grievance, are usually psychic invalids, as a result of unhappy experiences in childhood; often like the anarchist who killed Empress Elizabeth—they are illegitimate. The assassins are living out some infantile conflict. The assassinations they perform are supreme efforts at self-justification, to make up for the miseries of thwarted youth.

No one commits suicide, says Dr. Stekel in a famous essay, unless he has a tendency to kill some other person. Conversely, no one commits murder unless he has a tendency to suicide also. Most assassins are desperate enough to perform the act of murder because they are disappointed in life; they arc misfits with no useful or happy activity; they are candidates for suicide and thus do not mind risking their own lives to kill someone else. In fact, their tendency to murder may arise from a desire to make a spectacular exit from life; they say: "I shall die, but before doing so I will take another with me."

Very often the assassin kills a statesman as a father-image. He blames his father for his precarious and ill-nurtured position in life (almost all assassins are poor) ; the prominent person he slays is, pyschically, his father, whom he holds responsible for his fate; the prominent person may be first admired as a father-substitute, then hated, finally killed. Or, Dr. Stekel proceeds, the assassin may love his father-sub| stitute enough to kill him; the bi-polar nature of love and hate is obvious. Brutus, for instance, may have killed Caesar because, his spiritual son, he wanted to be closest to Caesar's heart, and saw himself displaced by Mark Antony. He murdered Caesar not because he hated him but out of jealousy. The kiss of Judas may not have been hypocrisy, but a real expression of love; Judas saw other disciples closer to Christ's favor than himself, and betrayed Christ because he could not bear to be in second place. As Oscar Wilde said, "Each man kills the thing he loves."

(Continued on page 62)

(Continued from page 60)

A perfect example of assassination caused by father fixation was the murder of the Austrian prime minister. Count Sturgkh, by a young socialist, Friedrich Adler, in Vienna in 1916. Friedrich was the inconspicuous son of the founder and leader of Austrian Socialism, Victor Adler. His deepest motive in killing Sturgkh was secret rivalry to his father. After the murder, delivering a magnificent speech in court, he was in the full light of public attention; his deed completely obscured his father's long and honorable career. He was a Socialist who completely upset Social-Democrat tradition; he did something. Friedrich turned to Sturgkh, and killed him, out of jealousy of his father; Sturgkh was a father-substitute. And, in reality, Friedrich killed his father too, at least killed his good name; old Victor Adler was completely crushed and his career obliterated by his son's crime, and he died ,soon after.

Dr. Stekel, pursuing this line of thought, referred to Hamlet, and delivered one of the most excitingly novel bits of Shakespeare criticism I have ever heard. He suggests the hypothesis that Hamlet believed that Uncle Claudius might have been his real father, and that this was the reason he was unable to murder him. Moreover, "to be or not to be" may not refer exclusively to the choice between life and suicide, but derives from the source of all doubt, which is uncertainty about one's birth. Hamlet was not sure he was the son of his father; he thought his mother's liaison with Claudius might go back to before his birth. Thus his projected crime became parricide, and doubly difficult.

A psychic injury such as doubt of the facts of paternity or any one of the innumerable trauma that may occur in childhood are permanent in a neurotic personality. They form a suppressed nucleus of eternal discontent with life. In extreme cases, says Dr. Stekel, they may cause murder. "The murdered king is in reality atoning for something in the hidden life of the assassin." An attentat is a displacement of a small personal conflict into the life of nations; the assassin is transposing the source of his unhappiness into the horizon of world affairs. Perhaps Booth was beaten by a drunken father. So Lincoln died. Perhaps Princip was doubtful of his mother's virtue. So the World War came.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now