Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe new king of Jugoslavia

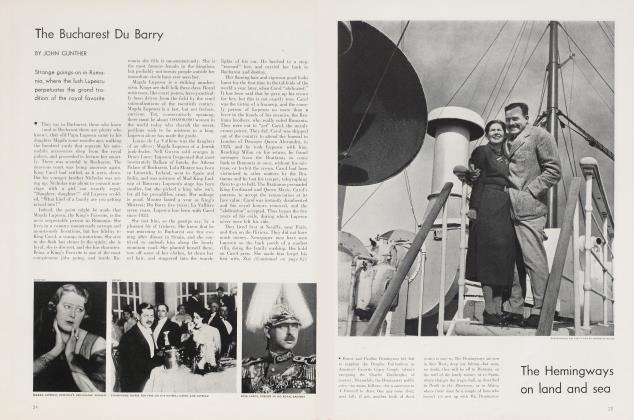

JOHN GUNTHER

Light on the dark future of Peter II, boy-king of a country where kings are a poor life insurance risk

It is not easy to write a character sketch of any boy aged eleven, let alone a king. Youthful royalties from Scandinavia to the Balkans are stamped of much the same metal from much the same machine; their families are cousins, their education is standardized, their character is a staple product, like a can of beans. Young King Peter II of Jugoslavia is in a slightly different class, however. Let us scan this lad, his lineage, his position, and his possibilities.

He became King of Jugoslavia, though, of course, he governs in name only, when his father Alexander was assassinated at Marseilles early in October. The death of Alexander was on the future books. He was not only king of his country and dictator; he was the most hated man in his realm. No Balkan king is a good life insurance risk; years ago I wrote of Alexander that his chief ambition was to die a natural death.

Alexander's father, Peter I, took the Serbian throne in 1903 following the murder of the King Alexander Obrenovitch and his notorious queen, Draga. Bits of their bodies were playfully flung from the palace windows to the mob. Peter's successor should have been the eldest son, George, but George was afflicted with an unpleasant temper and, when he thrashed one of his valets to death, he was certified as insane and interned in a fortress at Nisch, where, so far as I know, he still is. Old Peter's health and brain gave out and the second son, Alexander, the one just murdered at Marseilles, succeeded him.

The family, of which young Peter is now the head, is called the Karageorgevitch ("Black George") dynasty. Unlike other royalties, they stuck to themselves. They were Serbs of Serbs, the bluest blood in the Balkans. They were, too, bandit chieftains, guerilla fighters, mountain desperadoes. The Karageorgevitches twist through the history of Serbia in the 19th century like a crimson rope. Old Peter went outside his country to marry, but only across the border to Montenegro. Alexander went as far as neighboring Bucharest, in Rumania, and his bride, young Peter's mother, was Marie, the daughter of Marie of Rumania and great-granddaughter of Queen Victoria.

In young Peter's blood, therefore, are corpuscles basically Serb, but also German, British, Rumanian, Russian in origin. He was brought up under the strict court protocol of the top Balkans. Princes, like head waiters, must know languages, and he had tutors in French, English, and German, as well as his native Serb. He was going to the Sandroyd School in Surrey, England, when he heard of his father's murder and his sudden elevation to kingship, responsibility, and the uncertainties and rewards of fame.

Peter's life has been very strongly influenced by his affection for his politically stern but personally charming father. Therefore one must examine briefly the dead Alexander's character. Alexander was a disconcerting and enigmatic phenomenon. He looked like a dentist. He was as hard-boiled as a professional riveter. Whole sections of his country detested him as a heartless tyrant; but many persons whom I know and trust tell me that in quiet evenings at the palace he was as charming and considerate a host as Europe knew.

He was interested in three things, money, power, and soldiers. He was voted about $1,000,000 a year by the Jugoslav parliament, a tremendous sum for a Balkan monarch. He was terrified of assassination and almost never showed himself freely with his people. He was the largest single owner of Packard motor cars in the world, having had 23. He liked to drive alone to garrison posts outside Belgrade, and, unannounced, see that everything was shipshape. His personal life was absolutely austere. Aside from the queen, he never looked at another woman in his life. He worked fourteen to sixteen hours a day, and always wore a uniform. In his reception room the only ornaments were glass showcases filled with models of field artillery and cross sections of heavy shells, burnished till they glowed like gold.

Young King Peter will doubtless live at Dedinje, his father's country house near Belgrade. It is hardly a palace; rather a comfortable villa; Louis Adamic in The Native's Return said, I believe, that it was walled with soldiers and armed like a fortress, with secret airplane fields and such inside the grounds, but I never saw much military display there, though heaven knows there is plenty elsewhere in Jugoslavia. Also near Belgrade is Topola, the ancestral Karageorgevitch home, where Peter lived as a boy.

In England Peter doubtless led the normal life of an English schoolboy; in Belgrade he was kept strictly aloof from contact with the common people. His only playmates were his two younger brothers, Tomoslav and Andrei. His mother, a sedate woman, with little of the hot eccentricity of the other royal Rumanians, keeps very close to him.

Peter's cousin, Michael of Rumania, could tell him a thing or two about kingship, because Michael was also a boy king for a few brief years, until his father Carol flew back to Bucharest and took his infant's crown away. Michael, I once wrote, is the only personage in history who has been king of a country with reasonable expectation of being king of the same country again, just as Carol is probably the only monarch on record who succeeded to a throne held previously by both his father and his son, as my friend Leland Stowe first pointed out.

Young Peter faces a far harder job than Michael; it is not his father who can return to succeed him; but there are 14,000,000 people who may demote him into the scrapheap of historical curiosities. The word "Jugoslavia" connotes to most Americans a vague Balkan something-or-other of no particular beam or bulk. But Jugoslavia is one of the most important and powerful countries in Europe; it stretches from the Adriatic to the plains of Hungary and from the Austrian border almost to the Aegean; its geographical position makes it the pivot of the Balkans and its army a force severely to be reckoned with; there are 14,000,000 Jugoslavs, and they are a nation of rugged fighters.

(Continued on page 64)

(Continued from page 24)

Jugoslavia has been torn by domestic quarrels and split by internal fissures ever since the war. The country was one of Mr. Wilson's aesthetic contributions to the peace of Europe, and it has never really ticked. First it was called the Triune Kingdom, being formed of a free union of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, with a lot of sub-nationalities thrown in, Bosnians, Montenegrins, Dalmatians, and so on. The idea was to unite all the South Slav peoples, but to keep them united has been a terrible job.

The two main partners, who became rivals, are the Serbs and the Croats. The Serbs are Balkan folk centering in Belgrade, orthodox in religion and militant in spirit. The Croats, centering in Zagreb, lived for centuries in the orbit of Vienna and represented a more European culture, and they are Roman Catholic. The Serbs fought with us during the war, the Croats (against their will, it is true) with the Central Powers.

Bitterness grew under Alexander until the chasm between Belgrade and Zagreb, between Serb and Croat, became all but unbridgeable. The Croats called the Serbs "Mexicans" and "bandits." The Serbs called the Croats loafers and trouble makers. The Croats said they would prefer even the old monarchy to the tyranny of Alexander's dictatorship in Belgrade. The Serbs scoffingly quoted the old proverb that if there were only three Croats left alive, there would be four Croat political parties. The Croats martyrized their murdered leader, Raditch, shot in the Serb parliament. The Serbs replied that the Croats had done everything for independence for a thousand years—except fight for it. And Alexander, representing the dominant Serbs, mercilessly dragooned the Croats into submission.

All this would be distressing comic opera but little more should it apply, say, to Australia, or even Spain, which is walled from Europe by its lucky Pyrenees. But Jugoslavia is part of the very heart of Europe. Italy on one side, Hungary on another, bitter little Bulgaria on another, hemmed Jugoslavia in, and each had designs on her territorial integrity and substance. The Jugoslavs, tough folk, never made things easier by being tactful. Moreover, they had powerful friends, notably France and the two other countries of the Little Entente, Rumania and Czechoslovakia.

The great penalty to being a dictator is that when you are gone there is no one else to take your place. Dictators do not encourage Assistant Dictators. Look what Mussolini did to Balbo or what Stalin did to Trotsky or what Hitler did to Roehm. The kingship of Alexander was the chief cement of the Jugoslav state, and there is no one remotely of his calibre to replace him.

The issue of peace or war in Europe, should a civil convulsion in young Peter's realm occur, would be flatly up to one man, Mussolini, exactly as after the Dollfuss assassination in July. Italy covets much Jugoslav territory because the seizure of Dalmatia would transform the Adriatic into an Italian lake. Italy has, there is little doubt, secretly encouraged and even subsidized the dissident Croats, Slovenes, and Macedonians. If Italy should take advantage of disorders resulting from Alexander's death, and encourage the separatists by force of arms, war would result.

Probably Italy will not do so, because no one wants a war this year. But it is a far from easy situation. Hysteria is raging through Europe like a malignant eczema; there is no telling what new fatal accident may occur, or what toll it may tragically contribute.

Young Peter, aged eleven, assisted by his regency, is ruler of the most turbulent people in Europe. It is not an enviable job. All the glamour of royalty, if there is any, is hardly recompense for the formidable strain which will accompany this unlucky young man's adolescence. He should be playing cricket; he must sit crusted in golden uniforms while his general staff salutes. He should, soon, have a girl friend around the corner; instead he has a court chamberlain. He has, moreover, the most terrible prospect in the world: he can never change his job, he is king for life, he can never for an instant escape the prison of his position, unless he is booted out. Do not say that romance has died from Europe. Or poignancy either.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now