Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMemoirs of an ex-flapper

TESS SLESINGER

In those days there was time and money for everything. The panic of 1905 had died as we were being born and our parents brought us up to feel that, so far as "nice" people were concerned, everything was immutably in its place. The century was young when we were young, the "nice" people lived where there were plenty of parks and private schools, the poor people knew their place and went about properly in rags; the only thing to fear (in those days of the Hendrik Hudson Centennial, 1909, which we witnessed from the roof of our eight-story sky-scraper apartment) was an occasional drunk rolling out of a pre-prohibition swinging door—and of course the Public School Children. And though we were New Yorkers, born and bred, though we grew up in the sound of grinding street-cars and played among the skirmishes of passing trucks, though we knew blue-birds chiefly by hearsay and had to take crocuses for granted, still we were not so badly off—for Riverside Drive and Central Park, where our nurses took us skating after school, the empty lots (which our mothers in vain pronounced Treacherous), even the forbidden streets where the poor people lived, with their Public School Children, were as dear and familiar and safe as the back-yards which we were born without.

In the morning there was the "I cash clo'es" man groaning down the street and at evening there were the men bearing ladders and lighting our city by gas; in winter there was Private School and in summer Vacation, either the Mountains or the Seashore (to which our Papas commuted) and returning in the late fall to find our enemies, the Public School Children, already back at work, as pale and tough as we had left them in the spring. We who attended Private Schools were both proud and ashamed, down on Riverside Drive, of our Fraiileins sitting in rows upon the benches, and, secretly, we envied and feared the Public School Children, invading our park at three o'clock with their oil-cloth-covered books slung by a strap across one shoulder. Sometimes a playmate was segregated with "Whooping Cough" on a placard on his back; and, from our sandpile or the playground swings, we waved, and the quarantined one would whoop back lonesomely over the hill.

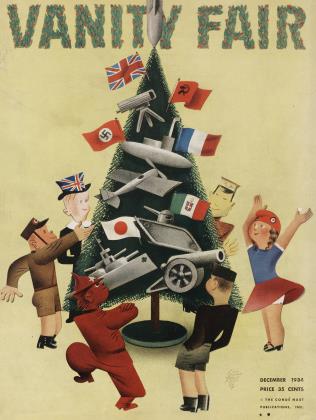

There is no telling exactly when the change began to take place, nor how it first manifested itself in our ten-year-old minds; but it is certain that that first decade of our lives was the only peaceful one we've ever known. It must have happened gradually, that our Mamas forgot to listen sometimes, that our Papas occasionally grew cross, that war stepped out of our history books and took possession of our street. Our friend the Elevator Man read the papers all day long, riding up and down from the first floor to the eighth; the maids hanging out washing on the roof quoted their fellows' opinions. All up and down the block the little girls playing hop-scotch began to murmur between twosies and threesies, Who're you for, Sister, who's your Papa for? My Papa's for the Germans, my Papa's for the French, my Mama's neutral—it's your turn, your turn, Leona! you've got to do twosies again! Until at School we learned to say Liberty Measles, the Public School Children all took up French; our Mamas said to eat every scrap of food on account of the Belgian children who had none, and our Fraiileins grew pale over their letters from home; until everybody on our block but the janitor's half-witted daughter had learned to shout The Allies! the Allies! my Papa says we CAN'T be neutral any more! and down on Riverside Drive our youngest brothers joined the Public School Children in turning the summer-houses into forts.

The Frauleins disappear somewhere, the Bohemian cooks drop their German fellows; the Elevator Man departs for the war with a gift of cigars from my father, and a woman with a waitress's bosom comes to take his place.

Then there came an abstracted look into our Papa's eyes, while our brothers of voting-age took to walking with their chests thrown out like cocks. And we grew up a little, we New York ten-year-olds, before our families had a chance to notice.

For our parents had turned their attention perforce to our older brothers and cousins, who had had their turn of neglect when we were born. At School we knitted wash-cloths—while they tried to reconcile the War with the Private School Good-Will-To-Men they had taught us the year before; on the streets we played at War; but at home our big brothers, sidling between sheepishness and awe in their R.O.T.C. uniforms, had become the babies of the family again, and we youngsters, puzzled and frightened, felt a little lost—and we missed our German Fraiileins.

And our homes changed; not gradually, but all at once. Our city, our small-town was altering before our eyes. The eightstory apartments of seven rooms or more were giving way to taller buildings, housing families in two-rooms-and-kitchenette—respectable couples went to bed, for lack of space, on the divans in their sitting-rooms; quite "nice" people, for a brief spell during the housing shortage, had their kitchens in their bathrooms; and all this with no Greenwich Villager's delight. The coalshortage left our houses cold, so that for one winter the only comfortable room in our house was the dining-room, in which we took turns dressing. We still had respectable addresses, but, actually, we were living little better than the Public School Children in their slums on Amsterdam Avenue.

In short, our Private School world was shot to hell.

Our homes were no longer the pleasant, leisurely open-houses that they had been; it was no fun to invite one's class-mates to the room where one's parents slept; the cooks despised their "families", turned snobs and misers, and were less ready to bake cakes impulsively. And beside all that, there was an air of worry in our homes that it wanicer to escape. So we took to the streets in a body, and upper Broadway was our Street. Flashy delicatessenrestaurants had sprung to life, and Chinese eating-places one flight up. Cheap jewelry shops, hosiery shops, souvenir stores, seven-dollar-dresses lent a transient, tourist air to what had been our slowly growing small town.

And so we who had never been to war emerged from it, and into a hard-boiled adolescence. We banded together; like our brothers in the army, we adopted a uniform. Like them we had our codes and traditions—and, God knows, a language of our own no sensible adult over seventeen could fathom. In short, we organized. We became Flappers and Collegiates. We still went to School (high-school now) in tamo'-shanters, middies, and leather coats; our families saw to that. But after school we donned our native costumes and assumed the curious characteristics of our tribe. Dresses to our knees, our coats thrown open, stockings rolled, and striped scarves flying, galoshes (no matter what the weather) loose and flapping round our ankles; bright weird hats with sporting feathers, our faces painted and powdered in the nearest telephone booth, beyond our mothers' sight or recognition. The object was to keep moving and to stay away from home as long as possible.

Our gait was necessarily slow, because of galoshes and the "college walk"; we marched arm in arm, Leona and I (when we weren't at the movies), with a drawling slow-motion, sliding as near to the sidewalk as we could manage, our flat bellies thrust out before us, our backs arched as for a swan-dive; we almost broke our necks with the effort to hang our felt-lidded heads like blase flowers. Our conversation, at fourteen, was divided between basketball and sex. We passed friends from other Private Schools and made scathing comments on their costumes, which were identical with our own.

"Frances! she was a wall-flower three times at the Horace Mann Christmas dance," Leona would confide; "spent most of her time in the ladies' room." Frances was prettier than any of us, as I remembered her, but she was "tame"; she didn't have a "line"; she wore taffeta instead of jersey to the dances and she was always wanting to be a "sister" to the boys. Discussion of the Charleston; Gilda Grey and the Shimmy; how the Japanese Gardens (wedged in between a theatre and a vaudevillehouse) was the darkest movie on Broadway; here we would stop off and listen to records—Kalua, Everybody Step, The Sheik, Japanese Sandman on one side of a record, with Avalon on the other. We discussed, further, how some really "nice" boys did go to Public High; how high-hat Charlie had grown since he went away to Exeter; how probably our parents did pet in their day but were never honest enough to admit it; how F. Scott Fitzgerald was the greatest writer that ever lived. "But do you really think—" I start to ask Leona; and she hushes me, for she has spied our boy-friends down the block.

(Continued on page 74)

(Continued from page 27)

This is the high-point of the afternoon. The boys weave toward us with the same slow-motion, their bodies slouched, their shoulders hunched, their trouser cuffs half-in, half outside the open galoshes. Like us, their open coats reveal flying scarves, their flat hats repose drunkenly over the right eye; under their scarves their four-button jackets close nearly to their ties.

Leona and I talk, with a kind of laconic animation, our eyes, as we approach the boys, turned away like parallel pairs of headlights; without looking we know that the boys turn their eyes away too, bending them toward the curb. It is only when we are almost abreast that we allow ourselves to give the tribal start of surprise and flip our felts at our class-mates. The boys, humming "What'll I Do," float past us, eyeing us infinitesimally beneath weary lowered lids, offering us a mockery of the collegiate salute, their hands too weary to more than touch their hats; Leona and I lift our brows a notch higher in bored salutation and can scarcely wait to draw out mirrors and see how we look at the big moment. "Morty's wonderful," I breathe. "Collegiate," Leona returns more correctly. When Leona and I dreamed about Morty, we did not dream about his magnificent basketball muscles exposed to us daily; we dreamed about the collegiate slant of Morty's hat, the look of the dope-fiend assumed in his collegiate sixteen-year-old-eyes.

In the Spring of 1920 we all became Shifters. To be a Shifter one merely wore an ordinary paper-clip in the lapel, hat-brim, or other conspicuous spot. The initiation consisted simply of carrying out any demand levied by a Shifter-member of the other sex. Ted, for instance, made Leona telephone a lady, picked at random from the phonebook, and inform her that her husband had just dropped dead at his office; Leona hung up in triumph on a woman distracted by sobs, and received her Shifter-clip.

(Continued on page 76)

(Continued from page 74)

But we were growing restless—we had a public now, and our public demanded something of us. We read about ourselves constantly in newspapers and magazines; we were eyed like some curious brand of expatriate and questioned as though we had dropped from Mars; by the world disapproved and of that world disapproving, we learned that we were a wild crowd, and we had to make good our legend. Life began at fourteen. We became acquainted with the interiors of taxi-cabs, and in the whirling little rooms we learned to drink like acrobats —on the wing, straight out of the flask. We discovered tea-dancing to fill our afternoons—we went more times than we were allowed (dressed in our jerseys and outlandish felts, our bright red mouths and flat-heeled shoes) to the Plaza, the Commodore, the Biltmore; we felt our power as we crashed place after place and captured it by making it unendurable to the older generation—and then when we had taken a place by storm, we coldly abandoned it and caused the rush to some place else. We began to crash the night-clubs too, and, pretty soon, there was no place in town where our parents were ashamed to be seen that we youngsters didn't know. We still adored basketball, we still got sick from bad whiskey, we still suffered pangs from our Private School conscience—but we had, by God, learned not to expose such weaknesses before the adults. We had made good our threats at last: we were as wild as our parents had feared, and more scared and more lost than any of them knew.

But we had been no more vulgar, in those days of the flapper-walk than the small-town belles and beaux whom Booth Tarkington makes so picturesque. We were walking the Main Street of our own small town—and a child's New York is that; we knew the shop-keepers, the soda-jerks, the cops and beggars, the new babies, even the dogs, as well as any inhabitant of Sterling, Illinois, could know his town.

It was not our fault that when we needed porches for our beaux, we had nothing but a Murphy bed in the living-room for holding hands. And it was neither our fault nor our parents' that we were carefully reared to be Private School Children in a rapidly strengthening Public School World.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now