Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHow to throw a cocktail party

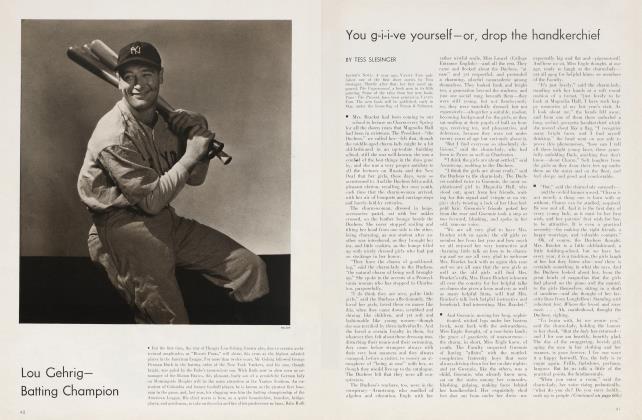

TESS SLESINGER

The answer is that you ought to throw it before it throw's you.

In the beginning there is the Name—a lion on whom you can hang the party. Someone is sure to point out the Name to you, one day, and say, "Isn't that the pudgy girl you used to room with?" Then you see the name everywhere. It becomes an item in the literary columns, a hideous blur in the best-seller lists, and finally a pain just behind the ears whenever you hear it—for you remember Pudge Skinner, who has suddenly become F. Edith Skinner, tagging along on double dates and borrowing your evening dresses to wear with your boyfriends. You want—remembering how she never would help you in English—to throw something at her: and you decide on a cocktail party.

You spend the week, after the first fine careless invitations have gone out, nervously sending telegrams to last-minute or nearcelebrities: writers who can just get by if you introduce them with their full name plus middle initial; painters who have not yet made their one-man show; a lady or two whose occupation is ambiguous but once had her name in F. P. A.'s column; a dancer out of a job; a gentleman-lecturer with a famous manner; an elderly gentleman who finances morning musicales.

On the very morning of your party— while the two Annies are making canapes all over the house, and while Albert, the elevator man, is bringing you strings of hideous chairs, which he steals (one at a time) from the unrented apartments below—sex suddenly rears its ugly head. You phone eight out of the dozen goodlooking youths you know, each of whom claims to be Joe Penner's exclusive gagman; a brilliantined cousin who shines in advertising; three pretty sisters who live in a basement apartment in Greenwich Village somewhere and are known as the Tiller Girls. This is known as Papering your house.

At this point—while you are begging the Annies to make their canapes anywhere else besides the sofa and piano—people begin to telephone you. The Tiller Girls want to know if they may bring their dinner dates. A dear friend would like to bring a person called Fred who is simply a card, my dear. Someone else has a house-guest, and you suppress a remark about the exterminator and say yes, yes, of course. And so the paper becomes confetti—and you ask the Annies to lace the cheese, and cajole Albert into finding fifteen more chairs.

A hasty survey, at four forty-five, assures you that the two Annies have achieved the improbable. The living-room is spotless, without a sign of an olive on a sofa, and the incredible canapes are lined up on sidetables like the hors-d'oeuvre in a Swedish restaurant. There is a nice refectory table, for the sophisticates with ulcers, who can only drink sherry or champagne, and you dig out a few tins of aspirin—usually reserved for your flowers—and scatter them behind palms and in the fireplace and other spots where people are most likely to fall.

The living-room, what with Albert's conscientiously-placed chairs, and the toomany flowers, now looks about as homey as a wake. The newly-arrived waiters look down their noses, like pall-bearers, and the two Annies, sneaking cigarettes in the kitchen, look as joyful as expectant heirs. As for yourself, you are undecided whether to play the undertaker or the corpse.

At five o'clock, faithful to their word, your six best friends arrive to help receive. You find yourself shaking hands with them very formally and asking, in sepulchral tones—though you had lunch with George and went to the theatre last night with Bob and Amy—how in the world they've been, anyway. The six of you sit unhappily on the edge of chairs and you keep wishing you could say you had to go home. You call for drinks, in an effort to put them at your ease. You all pick up a bit, laughing hollowly. Conversation lapses again and ultimately dies. The silence speaks volumes —trilogies.

A few more of your old friends enter awkwardly and the waiters are outnumbered two to one. The first of the ulcer brigade arrives, and takes up his station in melancholy splendor by the infirmary bar. The "card" arrives and alienates you at once by engaging nobody's sympathies by insisting on showing how he can remove his vest—without removing his coat.

The "house-guest" arrives and endeavors to prove, by a hasty survey of all exits into smaller rooms, that she is thoroughly housebroken. The family doctor comes next and you realize that no one is going to think he is cute except old measles patients. Fast on his heels come the Tiller Girls and their dinner dates. Your spirits pick up halfheartedly; there is really beginning to be quite a sickly-looking crowd. But you realize that you have papered your house so effectively that not a seat remains for a celebrity.

George continues to urge drinks upon you and, in a blind moment—after resenting his plying you with your own liquor— you give away and take that one too many; on turning, you perceive that your party, behind your back, without benefit of hostess, has become a party.

It looks like the crowd in a subway accident, everyone standing, swaying, screaming. Among the strap-hangers you observe not a single famous face. You long to mount a chair and raise a megaphone to your lips crying: "Is there a celebrity in the house?" when you feel a timid tap on the arm which will not be shaken off by your pointing impatiently to the door on the left, and, turning, you see Pudge.

Your guest of honor is wearing orchids to prove it, and a tiny fountain-pen hanging suggestively round her throat. She looks so funny and frightened that you want to sit her down in a corner and just let her autograph your whole set of Dickens, but your fine old hostess blood rises hotly and you drag her screaming to one group after the other, introducing her, first, conscientiously, as F. Edith, narrowing down to Fedith, and finally winding up with just plain Pudge.

"I knew her when," you roar at indifferent friends. "But why," some wag shouts back, who will certainly not be invited to your next cocktail party, if you should be masochist enough to give one. Pudge keeps playing with her fountain pen and her Phi Beta Kappa key, and you drag her past the Tiller Girls and the Penner Boys and deposit her where the "card" is trying to muscle back into his vest, still without removing his coat.

Now you fling about, madly tearing apart people who seem to be having a good time and dragging them either to Pudge or to somebody else whom they are sure to hate. You introduce a Mr. Jones to a Mrs. Smith and they reply acidly that they used to be married to each other; the present Mrs. Jones gives you an ugly look and tries to make trouble behind a palm with the present Mr. Smith. You helpfully introduce a writer to a critic, and leave them glaring at one another, the writer wishing to knowjust what the critic knows about Idaho, and the critic suggesting that the writer—a native of Idaho—go back to where he came from. Your good friend George, whom you begged to rescue the shy little blonde houseguest, is rescuing her with such enthusiasm that her hair is coming down in back; George is in a positive glow of righteousness; and when you icily suggest that someone else might like to meet the blonde, he pats you and explains kindly that the blonde would not like to meet anybody else. Mrs. Jones has been pulled back after she got her torso out of the window in an abortive effort to end it all, and Mrs. Smith is having a crying jag under the sofa with Mr. Jones.

The only quiet corner is occupied by the Guest of Honor, sitting lonely as a cloud and twice as unnoticed, her lips moving stealthily. You creep closer. No, she is not muttering, she is not cursing, she is not praying. She is happy, as always, with a good book; in this case it is her own book. She must have brought it. You sneak away.

The ulcer boys are making themselves popular by distributing sips of their champagne, the theatre stooges have been invited everywhere for the next week, in return for copying down ladies' addresses; someone discovers, on opening the pantry door, a prostrate figure embryonically leaning against ⅛⅞ ice-chest and trying to embalm itself; and you find two of the Penner Boys in the kitchen, dating up the Annies.

Continued on page 59

Continued from page 47

The "card" has now got nine-tenths of the party trying to get out of their vests without their coats, and the remaining tenth are trying to tempt the hysterical Mrs. Smith out from under the sofa by dangling a cocktail at the end of seven men's ties strongly knotted together. The guest of honor has finished reading her own hook and sits with a dreamy smile on her pudgy face, and in the shade of the piano the damned blond house-guest is sitting on George's lap and reading George's hand.

You advance with your heart on your sleeve, trying to conjure up images about "the last lap", "the homestretch", "the word go", hut nothing comes of it. You mutter about people going home 'soon if they want to get ahead in the world, and the "card" rejoins drolly with "And what a head."

George remarks that you are so impolite you must be in your cups, and you reply snappily whose have you a better right to be in. And then you give it all up, and slip outside in search of your hat and coat. You make the rounds politely, shaking hands and explaining to people under couches, half-out windows, locked in ice-boxes, and sitting in the fire-place, "So sorry I have to go, I've had a simply lovely time." They respond sleepily, "Nice you could come." Bitterly you approach George and the blonde. "Thanks so much, it's been wonderful," you purr. And George looks up—"But you must come again, my dear, we'd so enjoy having you." You stagger past the sleeping Mrs. Smith, the crying Mrs. Jones, the Tiller Girls—who, with their dinner dates, are having their dinner right here—and you run into your guest of honor, Pudge. Pudge is running away from it all, too. You've always liked Pudge. She suggests supper in some cosy little tea-room, just the two of you, and she will read to you from her book. Dear, dear Pudge. The two of you slink out, unobserved.

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now