Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe old lady counts her injuries

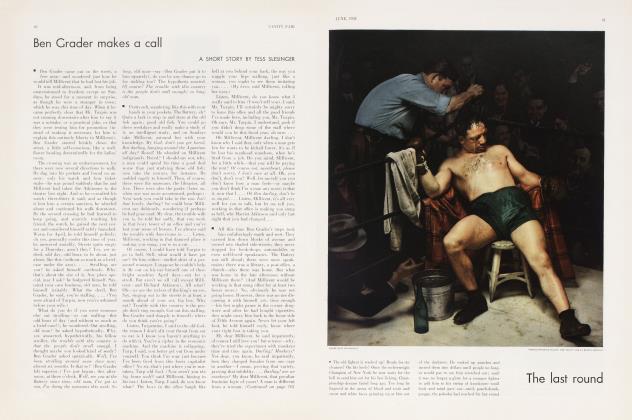

TESS SLESINGER

For the third time the old lady walked up to the information booth, approaching with the question on her trembling face that she was ashamed to put into words again. For the third time the clerk shook his head before she quite arrived, carrying his chin to a precise spot above his right shoulder and quivering it like a doctor pronouncing a bad diagnosis against his will. A kind of professional sympathy spread into his face, when he perceived her age again. "If you could tell me what he looks like?" he suggested, his jaw swinging back to center.

The old lady stood there, feeling a silly, fatuous smile crawling on her lips. He is a darling little boy, she wanted to say, in a sailor-suit and a big hat with a navyblue band; his hair is cut Buster Brown over his eyes, his upper front teeth are missing and the lower two just coming in; we think his teeth are not coming in quite straight, she thought of saying. For a moment she stood there, as little able to control the smile as to stop the slight, inquiring waver of her head that age had brought her. And all at once her face grew rigid, for she could suddenly not picture her son as he must look today. "Never mind. Thank you," she said, carving out the words to make them perfect.

She turned and walked primly out of the clerk's cold sight. I am an old lady, she thought indignantly; he has no right to keep me waiting so. I am an old lady and still he is as inconsiderate as he was when he was a child; he is an ungrateful son. She walked, distraught, about the station; sat down at last upon the edge of a bench, denying herself what comfort it might have given her. T am an old lady and I am very nervous and sitting about stations makes me sick and he knows it, she thought, whipping herself up to a frenzy of nerves that played in her tired muscles until they ached. I feel faint, she thought angrily; what if I should topple over on this bench and die, just as he comes swanking into the station, supercilious and fine, coming too late to meet his old mother. .. .

The thought gave her sustenance and she let herself sway on the bench with one hand to her forehead, pleased to imagine that she attracted interest from some passersby. Why, yes, we saw her, they would tell him, she did look ill, your mother, was she? She pictured Harry kneeling by her side; and then in spite of herself she pictured him rushing to a telephone booth—Evelyn mustn't worry!

Evelyn! In the presence of her daughter-in-law, the old lady always felt a mild disdain, flying to do her bidding nevertheless—to keep the peace with Harry, she told herself. Those awful week-ends in Evelyn's house! the old lady would keep up a steady stream of silent abuse against her daughter-in-law as meekly, and yet sarcastically, she put down the child if Evelyn said to, or stopped brushing her hair because Evelyn said it would take out the curl. Very many things had the old lady submitted to, and found only petty revenge in the righteous silent diatribe, or in an occasional furtive glance at her son. When she thought of Evelyn she thought again of the cruel day they had sprung through a door at her, Harry and Evelyn, to attack her with their news; to stand there grinning, hand-in-hand, as though to emphasize her age and loneliness; and to this day she could call back to her face the grimace she had made when Evelyn slyly called her "Mother." That Harry had not bothered to tell her by himself had been the first symbol of his handing together with Evelyn, that day and forever. The old lady felt a moisture gathering in her eyes.

• Inconsiderate he had always been, but this was the worst—and the last, she told herself grimly. They had already missed the two-seventeen. But she would wait for him—oh yes; she would wait only to tell him what she thought of him, of him and his fine Evelyn. She would not come down to their country place and be told how to treat her own grandchild, neither this weekend nor ever any other. That was over. She had learnt her lesson, she said brokenly to him in her mind; Evelyn has taken you from me, she sobbed, and I may be old but I am not a fool, 't our father would tell you a thing or two he were alive, young man, she wept, and she wept for the image of his father whom she saw vividly now as he had been in the '90's, when Harry was a child. But at once the image grew blurred and foreign, as though she herself, even at tin age of seventy, had outgrown it. just as she had outlived the young man with the sweeping black moustache who had been Harry's proud young father. She found as little comfort in the memory as one would find in a daguerreotype he had died and she had gone on, and now Harry was all that was left to her.

She would hold out to Harry, reproachfully, the gift she had bought for her grandchild, that she had bought with a fleeting nostalgic pain and felt was really for her son. Here, she would say, bitter and ungracious, take; it, take it to my grandchild. I am not coming with you, not today and not ever again. Once and for all let us have it out between us, she would tell him I don't like Evelyn and she poisons your mind against me; 1 11 not have any strangerwoman's child calling me Mother like that, telling me what 1 may and may not do with my own grandchild, my own son's child. That is over, Harry, she told him firmly in her mind, and suddenly stared about the station with the blackest apprehension in her bones.

She was a nasty, cruel, selfish old lady, not fit to he a mother, she tormented herself now—for what if something had happened to Harry! Now her hand flew in genuine pain to her heart, and her heartbeats came like the knocking of hail upon a window-pane. She remembered the day they had brought him from school with a broken leg; the wild, hot night she had spent on a train going up to the Adirondacks because they had telephoned something about an appendix; she felt again the black horror of apprehension that she had suffered every time her boy was not home by ten minutes past six for his supper. She saw him groaning on his little bed as they tenderly slipped his sailor-suit off his wounded leg; she felt her own hand again on his little stomach that was so while compared to his sun-burned legs as he lay, sheepishly glad to see her when she climbed the wooden steps to his tent—in a tent they had kept her little boy, while his appendix nearly burst within him! She saw herself pressed to the interminable nursery window, peering down the winter-darkened street, her heart in her throat until she saw him round the corner, carelessly swinging his baseball hat. . . .

Continued on page 79

Continued from page 23

He was coming, and what he carried in his hand, instead of a hat, was a brand-new hag of golf-clubs. Relief was so quick that it sickened her, apprehension turned to gall in her month. The mist in the old lady's eyes was drawn hack instantly, leaving them bright and hard. That, her son? Her little hoy in a sailor-suit? That stout and aging man, carrying his belly like a portent before him, looking like a thousand other middle-aged commuters who had been beautiful babies hack in the '90's when their papas moustaches bent to tickle them? She felt hitter and cold, and she shook with an unhappy kind of laughter at the grim revenge which time had played on her little boy.

She could see him advance in a straight line a little way, then veer sharply, looking about the station. He put down his hag of golf-clubs and she could sec him ridiculously scratch his ear; and then he stood, middle-aged and childish, looking for his mother. At once she rose and started toward him, in an agony of fear lest he have a moment's worry.

To her delight it was she who surprised him, she who had the foolish pleasure of saying first, "Oh there you are!" when she stole deliberately up behind him. Beautiful was his smile when he bent in relief to kiss her, beautiful his voice as he greeted her with joy. "Mother! we missed a train, I'm sorry, I rushed so I didn't even stop for lunch. We can just make the next one if we fly!"

He darted ahead of her, golf hag and all, and she tottered after him, worried to death about his having no lunch. "You ought to know better," she gasped; "running around like that on an empty stomach, you could catch anything, I think that's awful." Her words were drowned in his joyful exclamation tossed hack over his shoulder: "We've got half a minute—are you with me. Mom?" Happier than she ever remembered feeling in her life before, she ran on, panting luxuriously: "There's nothing more important— eating regularly—I've always told you that—" "Had to stop," he threw hack over his shoulder, "and get these new clubs for Evelyn, wouldn't dare face her if I hadn't—" But the old lady didn't hear his words with any part of herself that mattered, for they were running past the information booth now and she caught the clerk's eye and nodded violently, pointing ahead with pride to the fine haunches of her little hoy romping before her, see. see, he did come, and isn't he a darling? We had his teeth straightened, his father and I, she wanted to shout at the clerk with his commiserating chin, and she felt fine and strong again even though she sensed that silly smile crawling fatuous and triumphant across her trembling lips.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now