Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

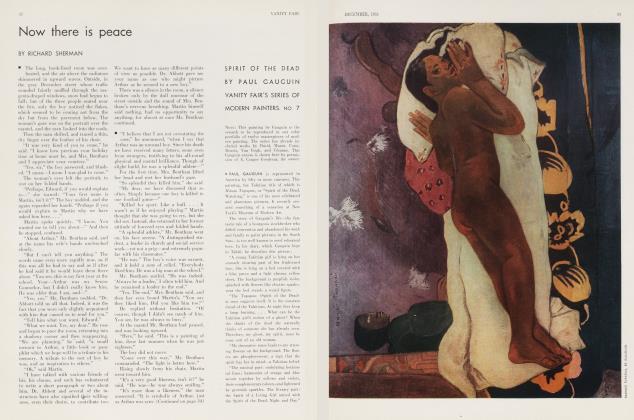

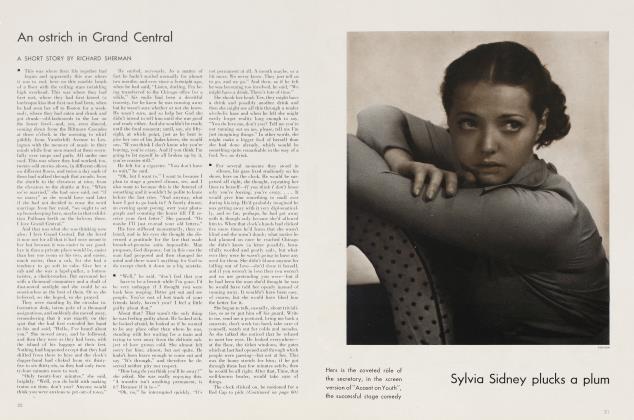

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMother and child

RICHARD SHERMAN

■ At five-thirty in the afternoon the place was all chromium and indirect lighting and smoke drifting in blue layers and ladies in silver fox capes sitting on white leather chairs sipping cocktails and talking to men with carnations in their lapels and circles under their eyes. It was a very smart place, a very chic place, where people rarely got drunk or if they got drunk never made any noise about it. Three Porto Ricans in Cuban costumes wandered among the tables with a guitar, a mandolin, and a pair of maracas. They played "Parlez-Moi Amour and "April in Paris and "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes" and "Hands Across the Table," and the little fat one sang the choruses in the kind of voice that is usually compared to a muted violin. At intervals they went aggressively Latin, and with a great deal of rolling of eyes and swaying of pink-ruffled shoulders did "Mama Inez" and "Siboney." And sometimes they just stood strumming their instruments idly, waiting for someone to get mellow enough to begin giving them dollar hills to play Irish tunes.

The woman and the girl sat on the wall seat, and the only way you knew which was the older was by the veins in the pretty one's scarlet-tipped hands and a sligliL thickening of her hips. There was something of her in the girl's face, hut there was more of someone else. If the girl had had the woman's eyes and chin as well as her straight, short nose, she would have been pretty too; as it was, she had gray, unexciting eyes and a too stern mouth, a man's mouth, and she was plain. She was plainly dressed, also, in an unimaginative hat and a dark, rough coat that looked as if it were used to having numbers of similar coats ahead and behind it marching in a regimented line toward an ivied entrance. At the moment, she was regarding the olive, corpse-green in the shallows of her glass, spearing it with a toothpick, and nibbling experimentally.

"Now I'm going to leave shortly after he comes, because 1 m meeting Freddie," said the woman, and if her voice had been a taste it would have been the rich grittiness of tropic fruit. She was dressed like next month's Vogue. "Then he can take you out to dinner."

"He didn't ask me to dinner," said the girl. "It was just cocktails."

"Well, he'll ask you if you're nice to him, won't lie?" She spoke in patient exposition, as if to a willing but dense child. "Really, it does seem to me that they might teach you charm as well as chemistry."

"They try to," said the girl. "All during last term we had social hour every evening. I learned to tango."

"With girls. A lot of good that will do you, leading all the time." She fingered her glass. "I suppose you do lead."

"Usually. They say I do it belter than anyone in school."

The woman smiled, rather wryly. "If you think that's a compliment, you're much mistaken. Now when I was your age—" she stopped, then placed her hand on the girl's, her bracelet dragging through a welter of potato chips and peanuts and two rouge-stained cigarette butts. "You think I'm an awful nagger, don't you, baby? And you'd rather 1 hadn't come. But it's for your own good, I swear it is. If you only knew how I lie awake nights wondering about you and that school. Sometimes I wish I wasn't sending you there at all. Education and refinement are all very well, but still. . . ." She sighed, and her lovely lips drooped. "Now this Edgar. He might he hopeless, he might be terrible, and you wouldn't know it. You have no basis of comparison; you've been too sheltered."

"He—" her tone was shyly defensive; "he isn't terrible. He's nice, 1 think."

"You think. Well, he sounds terrible— that talk about science and everything. ' She snapped her toothpick neatly in half. "Is he serious?"

"Serious?" said the girl. "Oh, you mean —" she laughed. "Heavens, no! After all, he's barely out of college, and anyway I've met him only twice."

There was a sudden desperation in the woman's voice. "I'd die if my daughter turned out to be a wallflower. Promise me you won't. Be silly or stupid or anything, but don't be a wallflower." She made a cross out of the two toothpick slivers, flipped them casually to the floor with her forefinger, and returned the inviting smile of the single man at the next table with a cold stare. Then she turned. "I expect that's very wicked advice to give you, but it's sound. Your father would have wanted you to he both good and gay, and it would he nice if you could be, but if you have to make a choice you'd better be gay. And you'd better be starting, loo. Freddie says you're too much of a mouse."

"I don't—" began the girl, and hesitated.

"You don't like Freddie, is that it? Anger appeared on the horizon like a redhot sun. "Well, that's not unusual, though he's very fond of you. You've never liked any of my friends. After all, I can't be expected to stay home all the time, can I? I'm not exactly Mrs. Whistler, you know."

"Don't let's quarrel, please," said the girl. "Not when I have to be going back so soon." Just as you could see the ghost of a man in her face, so you could hear his voice; a voice of mediation and reasoning.

There was a silence, and then the woman spoke. "It was my fault," she said. "I certainly am the darnedest mother."

The girl smiled, comfortingly. "You're a wonderful mother," she said, and then her eyes, turning toward the door, miraculously changed from gray to blue. "There he is," she said. "There's Edgar."

When he joined them there was confusion at first: introductions and the waiter taking the orders, a party leaving at a nearby table, a scraping of chairs, coats brushing the backs of people's necks as others came and went in the room. But at last there was calm, and a certain kind of nervous peace, and the three Porto Ricans playing "Stardust."

The man was young, square-jawed, well-built, and the first thing he said, when comparative quiet reigned again, was, "Janet's spoken of you."

"I shouldn't have come uninvited, should I?" said the woman. Her eyes were taking inventory of a pin-striped dark suit, a white handkerchief peering decorously from the breast pocket, a blue tie, and a forehead that swept back clean as a beach to a dark hairline. "But Janet has so little time left. Don't consider me as a chaperon, because I must go shortly."

"New York is too big," said the girl. "We've lived here all our lives, yet Edgar had to go to Boston so that he could meet me, and I had to come back from Boston so that I could introduce him to you, Mother. Isn't that strange?"

They agreed that it was very strange, but then so many things were strange in New York. Take the weather; they took the weather, the three of them, and went through it like a four-course dinner, from spring to spring, after which they were left treading water, panting slightly, and seeking another raft to cling to for a while.

"Do you live in Manhattan, Mr.—I'm sorry, but Janet always said Edgar, and I didn't get the last name." There was a winsome helplessness in her confusion.

"Gregg," he said, "but the Edgar's all right too." He was seated opposite them. When he stared straight ahead he was looking at a naked nymph chasing a second naked nymph toward the nearest exit. When he turned his head to the right, he was looking at the girl; when he turned to the left, at the woI man. At present he favored the left. "Yes," he said. "Just a one-room apartment, hut I like it better than a hotel or a club."

Continued on page 70

(Continued from page 28)

The woman, it seemed, had a great deal to say about hotels versus small apartments, and said it. She preferred a hotel any time. Under her guidance, a spirited yet amiable dual argument sprouted, blossomed, and ultimately withered. The girl sat by, uncertainly and silently. When she saw a break in the conversation she slid swiftly into it.

"We've been to a matinee, Edgar." Her tone said, I'm here too, don't forget me.

"What did you see?" he asked, and then said that he had seen it too. The woman remarked that she hadn't liked it, though Janet had—but of course Janet had a very fine mind, inherited from her father, and could appreciate things like that. "It's too morbid for me," she admitted, with a rueful frankness. "I'm the horrible type that goes to the theatre to laugh. To musical comedies especially. I suppose you don't go to musical comedies, do you, Mr. Gregg?"

"No," said the girl, firmly. "He doesn't."

"Some of them 1 do," he protested.

"He goes to the Guild and things like that," said the girl.

The woman shook her head. "I'd give anything to be able to enjoy serious plays—honestly enjoy them, I mean, not just pretend to." She smiled at the man playfully. "I'm afraid we'd never get along, would we? We seem to disagree about everything." But disagreement had somehow produced an intimacy, and when he extended his lighter for her cigarette she looked up at him over the flame companionably. They weren't strangers any more. The girl was the only stranger at the table, and everything she said led to a blind alley. Several times she entered heartily into the conversation, as if at last here was something she could get her teeth in, but it always petered out. Meanwhile the woman's voice rippled on, richly, adroitly, asking questions, starting stories which she left unfinished, stopping now and then to listen courteously to the girl and then resuming the main thread.

The people in the room were thinning out now. Suddenly the girl said. "Freddie."

The woman interrupted a sentence long enough to look at her in mild I curiosity.

"Freddie," repeated the girl. "Isn't it time for you to meet Freddie?"

"Oh," answered the woman. "You know, I don't think I could bear Freddie alone for dinner. I tell you," and | her face brightened, "why don't we all eat together?" She turned to the man. "That is, unless you and Janet had other plans."

"Why, no," he said. "I'd like very I much—"

"It's her last evening, you see, so I'm being selfish. Afterward we can all go up to Freddie's place for drinks. He plays the piano marvelously. We ll have a sort of a party, to celebrate Janet's last night of freedom. How'll that be, baby?" The atmosphere had become i very gay, made so by the woman's enthusiasm. Her electric vivacity foretold the party itself -music and laughter and fun—and her eyes were shining and she looked beautiful. The man was smiling; not at anyone in particular hut just the innocent, open smile of one who has been pleasantly surprised.

"I ought to pack," said the girl in a tone whose flatness might have deflated the jollity if the woman had not replied, "Nonsense, you can pack any time. You can pack on the train." She laughed delightedly and unselfconsciously at her own wit, then turned soberly to business. "Now this check is mine," she announced to the man. "I asked myself, so I insist on it."

"Oh, no, I can't let you do that."

They squabbled about it merrily, and finally she relented, with mock bitterness, and let him pay. He then excused himself, and the two were left alone, pulling on gloves and adjusting hats. The woman talked steadily about the color of a dress across the room, which she said was the most extraordinary color she'd ever seen. "It isn't red and it isn't cerise either. What would you call it, baby? Would you say it was—" she turned. "Why, what's the matter?" The girl had begun, not to cry, but to bite her lips as if she were about to cry.

"Nothing," she said, wrapping an olive pit in a shroud of cigarette ashes.

"There is too," said the woman. "You can't sit there looking like that and tell me nothing's the matter," she argued, although the threat of tears had now vanished.

"I suppose you can't help it," said the girl. "I doubt if you even realize it."

"Realize what?" Disaster averted, she had taken out a mirror and was examining her face in it critically. "Honestly, Janet, sometimes I don't know what to do about you. You ought to he feeling thankful."

"Thankful for what?"

Site replaced the mirror in her bag with a long sigh. "For my rescuing you from an evening alone with that man. Heavens, what a bore!"

"You didn't talk to him as if you thought he was a bore."

"Darling, I was being polite, don't you understand? Somebody had to talk, certainly. You didn't, and he didn't. I doubt if he can."

The girl's voice was low. "He talks to me when we're alone. It's just that you—" she stopped.

The woman looked at her incredulously, and suddenly began to laugh. "Janet, baby, you don't for a moment think that I—no, you couldn't, it's too ridiculous." Then her face was serious. "Really, he's impossible. I'm certainly glad I came."

Slowly the girl raised her head, and doubt was like a fog in her eyes. "Oh." she said, after a long pause, "oh, I wish I could trust you."

And then they both looked up and the man was standing beside them.

"All set?" he said, smiling.

He helped the woman into her coat first, naturally, since she was the elder, and as she drew her collar about her lovely chin she said, "You know, I think maybe I will call you Edgar, after all; or maybe Eddie. Mr. Gregg is too formal."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now