Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

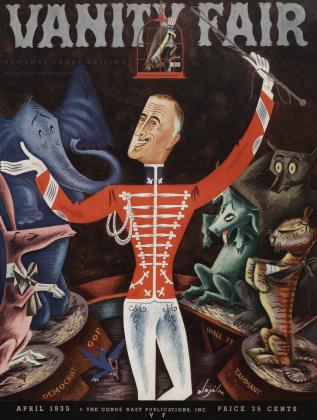

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRUDE AND HONEST ICKES

RAYMOND GRAM SWING

A brilliant solution to the pressing public problem: if x = honesty; y = tactlessness, x + y = Secretary Ickes

■ Harold L. Ickes, Secretary of the Interior, is the sore thumb of the Roosevelt administration. The thumb is the stubborn part of the hand, and when it is sore it sticks out. Mr. Ickes is stubborn and he very much sticks out. He is being repeatedly run into, and when there is a collision a pang of pain shoots through the whole administration. Mr. Ickes is also a sore thumb which does not heal. He will always slick out, and will go on being run into. That is the most important truth about him, and it can be stated in another way: Mr. Ickes has no aspirations to be more than Secretary of the Interior. He is not plotting for more power. He will not yield in this or that particular to promote his ambitions. 1 bus he would be rare in any Washington hierarchy, where the rule is to scheme just a little at least for personal advancement, and where decisions of slate are usually measured in two ways: first as to how the public will react, second as to what it will do for the one who makes it. If Mr. Ickes were only a politician he would be a comfortable thumb, and could be folded under enclosed fingers now and then.

When Harold L. Ickes became Secretary of the Interior he stepped into a position of power beyond any of his dreams. He had been a not conspicuous liberal Chicago lawyer, devoting much of his time to fighting lost causes, in the days when Donald R. Richberg, one of his partners, was a left-wing liberal. Mr. and Mrs. Ickes had a specialty, Indians, the most picturesque of all lost causes. Mr. Ickes, a progressive Republican, worked for Roosevelt's election and came to Washington before the inauguration hoping to be given the political reward of the Indian Bureau. He met the President-elect for the first time, and there was enacted that unusual drama of two men intuitively understanding each other at first sight. I he President recognized in Mr. Ickes an honest and able man. He had been looking desperately for such a man to be Secretary of the Interior. He knew at once he had found him.

The Interior Department is the treasure-house of the American nation. To be Secretary is like being porter in charge of a room full of gold. He can use the trust as a loyal servant, which requires indifference to a glittering array of subtle temptations, he can use it for financial benefit, or he can use it to gain more and more power. The department has the trusteeship of all the undeveloped natural resources of the country, the wealth of the future generations of Americans. It has control over the American colonies. It also controls the destiny of the American Indians, and maintains the parks and forests of the public domain. It takes a man with a vivid imagination to picture to himself the vast value of the resources, and the almost terrible public responsibility of being Secretary of the Interior. Mr. Ickes came to the office with such an imagination. And to make his task more herculean, he was given huge sums to administer on public works. It is the double burden which has been too much for Mr. Ickes' tact. As Secretary of the Interior he might have managed to be honest and not unpleasing at the same time. But it was beyond any one man's command of courtesy, consideration and patience to be both a porter of a gold-house and a spender of billions. I bus it has been Mr. Ickes' misfortune to be known as the rude slow man of Washington. In his determination to be honest he has come to be ponderous, awkward, suspicious and nosey, particularly nosey. He refuses to spend money he does not know is honestly spent. And if dishonesty does not appear on the surface of a project, he takes the time to look under the surface.

The administration was out for huge spending as a stimulus to recovery, and if its full effectiveness was to be felt it had to be done quickly. Mr. Ickes did not spend quickly, and recovery so far as he was concerned had to wait. People in Washington, watching the two spenders in action, Harry Hopkins at PER A and Mr. Ickes at PWA, saw that both of them were phenomenally honest, but wished they might exchange jobs. Mr. Hopkins could be both honest and in a hurry; that would be excellent for recovery. Mr. Ickes was honest and deliberate; that would be excellent for relief. But Mr. Ickes would not be speeded up, and while he probed into every sizeable spending proposition, he also planned seriously, and built up a system of inquiry and investigation, so that future spending can be competently and organically organized without haste and without waste.

Anyone with knowledge about such matters will admit that Mr. Ickes runs the most honest government department in Washington. But he has won this reputation al a price. Some of his employes arc under a strain. They feel themselves spied on and checked, not the best feeling if they are to put their hearts into their work. Mr. Ickes may realize this and regret it, but he probably would tell himself that it can't be helped. His method has caught more than one incipient misfeasance, which is what he knows he is there for.

The attitude of suspicion toward a department may be forgiven, but if it is directed toward Congress and businessmen it is bound to create resentment. Mr. Ickes has accumulated a larger list of enemies than any man in Washington. Politicians don't like him because he refuses to play politics with appointments and appropriations. They like him even less for being a Republican in the Cabinet, a Hag of hi-partisanship in a partisan country. They would not mind if elections were on a coalition basis. But politicians have to play politics to get office, and politics being a great exchange of goods and services, and Mr. Ickes, being guardian of both resources and cash, he is in a position to spoil much of the game. Congress was worried over the President's four-billion-dollar far relief-work project chiefly because Mr. Ickes might have the spending of it. An emissary from the White House had to hurry to the Capitol to assure the House of Representatives this was not to be before it would pass the bill. Ibis is an extraordinary fact to record about any man. It shows how Mr. Ickes has become a symbol of frustration in political life. If only he were more ambitious be might turn such a reputation to good account, since on the whole America would rather see honesty than political commerce in Washington. But he does not aspire, he is fully burdened as it is. Instead, he lets his public reputation be made for him by his opponents, who paint his portrait as a boor, a tyrant and a tiresomely honest person. And he has made one unfortunate misstep in moving to get Robert Moses of New York off the Tri-Borough Bridge Authority, a glaring inconsistency for a man who refuses to play politics.

The Moses incident adds complexity to the analysis of Mr. Ickes as just a man with an inordinate imagination about his public responsibilities. But it is not a very complex affair. Mr. Ickes has great affection for the President and the deepest loyalty to him. This counts even more than the fact that as cabinet minister be is subject to bis instructions. It is legitimate to surmise that the President was the one who wanted Mr. Moses ousted and asked Mr. Ickes to do it. The research into the Moses affair must be moved to the White House, or perhaps farther back in history to Albany. Once Governor Roosevelt and Mr. Moses were great cronies. Then came the fateful day when Mr. Moses sided for A1 Smith, since which time the divergence between the former pals has drastically widened. During the last campaign, Mr. Moses was ferocious in bis attacks both on the New Deal and on Governor Lehman. Yet be held a job under the state and one under the federal government. After the election he continued criticizing bis two employers in public and in private. So the President may have explained to Mr. Ickes that Mr. Moses should stop working for the state and the government, or he should have the grace to stop attacking them. And since he hadn't the grace to do either he was due for the reprimand of losing one of his jobs, one job being enough for one man in these hard times. Behind the reprimand, moreover, lay the still deeper consideration, if he can he so described, of State Democratic Chairman Farley. Right off here is an irony. Mr. FarIcy is the holder of not two hut three jobs, since he is state and national chairman as well as Postmaster General. In all three jobs it is his natural function to see that good Democrats occupy lucrative public positions. Mr. Farley's hopes of rewarding the wheel-horses were sure to he disregarded ha Mr. Moses so long as he remained on the Tri-Borough Bridge Authority, since Mr. Moses is quite as honest as Mr. Ickes and as an employer quite as loath to yield to political pressure. The situation developed ironies for Mr. Ickes too. Here was he, the tactless, being chosen to excommunicate Mr. Moses for his had manners, and he, the nonpartisan, becoming the instrument of the arch-partisan, Mr. Farley. And yet what should he do? Refuse the President and resign? Such an idea surely did not cross his mind. Nor is it likely to have occurred to him that he might simply beg off, pleading for Mr. Moses as his own friends do for him, that honesty is of greater moment than manners. He might have used as a warning at the White House the phrase that was later embodied in a wise-crack at the Dutch Treat Club about Mr. Moses being "the only honest official in New York . But instead he loyally became the scapegoat, set out to remove Mr. Moses and to accept all the confusing consequences, though surely without realizing at the time how unpleasantly ironical they were going to he.

At every point, Mr. Ickes seems, out of sheer conscientiousness, to put a spoke in the Administration's wheel. When Senator Huey Long charged Mr. Farley with pursuing an extensive and profitable private life in the contracting business simultaneously with his incumbency as PostmasterGeneral, and this against all precedent and custom, it was Mr. Ickes's unhappy lot to he ordered to supply the information against Mr. Farley from the PWA files.

Mr. Ickes may appear to he tiresomely honest hut he is not the Puritan who delights in enforcing probity simply because it keeps somebody from doing something. As a human being he is a genuine liberal.

Unfortunately lie does not wear the armor of insensitiveness so essential in his vulnerable position. When he is criticized it hurts. He has not the experience in office nor the temperament to know that critics are never going to understand why he does what he does, and judge him from his own standpoint. And when he is hurt he takes his escape to his garden or his stamp collection. It is a bright incident that Postmaster General Farley should have found himself in hot water for giving him, among others, a set of valuable contemporary stamps and that Mr. Ickes of all persons should he receiving something in a way to stir talk of a congressional investigation. But Philatelist Ickes was the one above all men in Washington to have appreciated Mr. Farley's gift. He keeps his stamps in frames, and derives from them much spiritual repose. When he is distraught, he often digs in his garden. But late at night, after working through the papers on his desk, and too disturbed to sleep, he can he found prowling about his house. He is changing the stamps in their frames, and hanging them in new places. And this he does often, for he worries a lot. Few people realize how much it lakes out of a man to run an honest Washington department.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now