Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhen lovely women stooped to the Follies

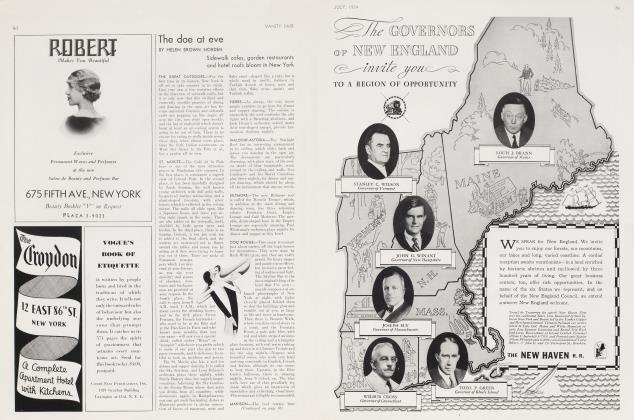

HELEN BROWN NORDEN

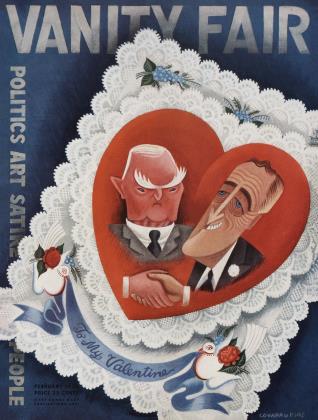

The editors of Vanity Fair have been assured that sometime this spring, if all goes well, there will blaze a new sign on Broadway, whose brilliant lights will form the word FOLLIES—a word which the Tenderloin has imagined banished forever from its demesne. In all probability, this will be its last public appearance. In memory of the man who once gave her a job, and who later became her good friend, Peggy Fears Blumenthal will produce a memorial to Florenz Ziegfeld, The All-Time Follies. Follies performers of another day will flock to the standard: Marilyn Miller, Leon Errol, Fannie Brice and the others. They will do again—for the last time—the numbers which first gave them fame under the Ziegfeld banner—the old songs, the old sketches, the half-forgotten dances. And a bright ghost will kick its gleeful heels about the neon bulbs—a naive ghost of other days, the spectral symbol of early-century gaiety. Ring—oh bells of memory. Dimly, ghosts, burn back to life.

In the year 1907, Klaw and Erlanger turned the roof of their New York Theatre over to a young theatrical manager named Florenz Ziegfeld, and there, on the night of July 8, a new species of creature sprang full-blown into the world and a new class-word was given to the language:—the Follies Girl.

Every once in a while, a nation coins a phrase which grows beyond its original descriptive significance and becomes a symbol of certain integral manifestations of that country's social culture. Rome had its Vestal Virgins and Japan its geisha girls; India flowered forth the soft-eyed temple dancers, and there were witches in Salem. Without going quite so far as to compare the late Mr. Ziegfeld's houris with the Vestal Virgins, it is still possible that in the anthropological sense, they too have given us an example of the phrase historic; a Follies Girl.

Now that the institution of the annual Follies is no longer a part of our national scene; now that there arc no more glamour-girls in training for that proud, exciting title of ExGlorified—the time has come to pass in review a few of those astonishing personalities whose Ziegfeld background was the starting-point which led them on a fragile, perilous chain to fame or wealth or death—or backward to the dark obscurity once more. From these examples there may come some flickering glint of the curious potency of the Follies trademark.

For the past twenty-five years, this species of feminine phenomenon has existed in America. unique and indigenous. There is no classification in the language which has the particular import, the peculiar, glittering magic of this one phrase. Its nearest counterpart in the modern world was the nimbus attached to the dancers of the Imperial Ballet of Czarist Russia. But the significance of the latter was neither so far-reaching nor so cogent.

Glamorous and already legendary are the image connotations which arise from the mere sound of the word "Follies". Chinchilla and orchids and ropes of pearls. Champagne drunk from red-heeled slippers at Rector's (If a Table at Rector's Could Talk ta-de—dum-dum-dum. . . .) and breakfasts at Jack's. The bunny-hug, the turkey-trot, the grizzly-bear (It's a Bear, It's a Bear, It's a Bear!). the tickle-toe, the shimmy and the Black Bottom. I Just Can't Make My Eyes Behave Swing Me High, Swing Me Low, Dearie.

So much of America is implicit in the phrase: the lavish display, the mushroom leap to fame and fortune, the quick oblivion. Just as every small American boy could hope to he President, so every American girl from rock-ribbed Maine to the Barbary Coast could dream of eventual apotheosis as a Follies Girl. The Follies were an institution—a training-school—an Alma Mater whose graduates wore the words, "a former Follies Girl," like a bright badge of merit for the rest of their lives; and even in death, that phrase alone, attached to their names, was enough to bring them front-page obituaries. A Follies Girl is always good copy, and the lustre of the name has shone on its bearers.in the police courts, in Burke's Peerage, in the Social Register and in Hollywood. Follies graduates made the millionaire-chorus-girl marriage popular in America and injected new blood and beauty into many an otherwise effete old family name. But whether they married millions or whether they went into opera, they brought with them the glamorous heritage of their training-school. Even in death, they were decorative and dramatic.

Continued on page 56b

Continued from page 27

To the observer of casual glance— and other outlying districts it may look as if every well known woman of the Twentieth Century were once a Follies Girl. This, of course, is not true. It is only almost true. Let us take a few of the more famed examples and see how they have penetrated into the veins of the world as no other specialized group of women has ever done. As another typical American symbol would say, "I.et us look at ihe record."

THE PATH TO FAME—Back in Evansville, Indiana, at the age of five, Marilyn Miller used to climb on a chair in front of a mirror and practice dancing steps. With her parents, sister and brother, she went on tour as "The Four Columbians". The act played Europe for seven years, until Lee Shubert brought them back to America. Then, as it must to all pretty girls of that era, came the Follies. For years, Marilyn w'as Ziegfeld's premiere danseuse. She married, and her husband was killed in an automobile accident. Later, she married Jack Bickford, probably—as she once admitted—because Ziegfeld told her he'd fire her if she did. After their divorce, she went to Hollywood, where she made pictures at the publicized rate of $150,000 a picture, a sum which was not justified by the subsequent box-office receipts. Of late, she has been more or less in the news background, emerging sporadically to affirm or deny her engagement to Don Alvarado—a movie hero, darkly sleek. One of these spurts of publicity occurred recently, when she and Alvarado sailed for Europe on the same boat, causing furious rumors of a secret marriage.

Mary Lewis' father was a Methodist minister in Little Rock, Arkansas. At eight, Mary was singing I'll Be a Little Sunbeam for Jesus in her father's Sunday-school. Eleven years later, she ran off with a road-show and was stranded in San Francisco, where she got a job singing in Tail's Cafe. First a chorus girl, then a prima donna, she left Ziegfeld for the concert stage. Then she came East. Her Metropolitan debut was in 1929. Critics tossed their verbal violets at her feet and for a while she basked in that sweet sunlight. Last fall, attempting a comeback, she was present at the opening of the supper club of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in New York and was asked to sing. In the midst of Carry Me Back to Old Virginity, a drunk tossed pennies at her feet. Gallantly she smiled, stooped to pick them up, and finished her song. Now she is again at leisure.

Bernard Douras was a South Brooklyn magistrate. He sent his blonde daughter, who had been posing for Howard Chandler Christy, to Ziegfeld with a note of introduction. From then on, she was a Follies feature for three years, under the name of Marion Davies. The rest is unofficial history. Her movie career has been long and flourishing: her establishments lavish; her home-grown orchids the most famed in America: and her reputation as a Hollywood hostess without peer. Last year, the government sued her for $1,000.000 income taxes. They compromised on $825,000.

Ina Claire, whose latest Broadway show is Biography, is one of the most famed of the Ziegfeld graduates. At thirteen, she was Ina Fagan of Washington, doing imitations of Harry Lauder. She was a Follies star in the days wh"n W. C. Fields was presenting his amiable Jewish comedy, long before Montague Glass sold his birthright for a mess of Potash and Perlmutter. Her Hollywood interlude— which included marriage and divorce with John Gilbert—the screen's one-time Great Lover—is now a part of the cinematic archives.

Most of the $39,000,000 of Sir Mortimer Davis, plump Canadian tobacco magnate, evaporated two years ago. Rosie Dolly sued him for divorce. But the marriage, with its tales of disinheritance, of parental wrath, of Lucullan splendor on the Riviera, had served its function in the public prints. Rosika and Jancsi Dolly, Hungarian twins, are world-celebrated figures now, but they got their start in the Follies. They are always good newspaper copy, whether they are marrying millionaires, breaking the bank at Monte Carlo, dancing with princes or lending their decorative bare brown backs to the Mediterranean sands. When the Moulin Rouge in Montmartre played up Mistinguette's legs ahead of the twins, they sued for 500,000 francs and got it. They are garlanded with bright legends and are practically a modern saga in themselves.

Dorothy Mackaill of the drooping mouth and Botticelli cheekline came from the music-halls of England to the Ziegfeld offices and the Midnight Follies. Marshall Neilan took her to Hollywood. Lilyan Tashman used to give imitations of Frank Tinney. She came to the Follies from a Brooklyn high school. Billie Dove's lucid features gazed serenely from magazine covers until the 1917 Follies, when she could be seen any night, swinging in a hoop hung from an elaborate artificial tree.

Then there are the others: Fannie Brice, whose great Follies song was l.ovey Joe; Norma Talmadge, now making personal appearances at picture houses; Gladys Glad, the Bronx Venus who came out of an Elks' carnival to the Follies and now conducts a beauty column on the Daily Mirror; Helen Morgan, who just got off the Showboat piano; Mae Murray of the bee-stung lips and Prince Mdivani; and Ann Pennington, who was September 1 lorn in the Follies of 1913 and is still showing her historic knees in 1933.

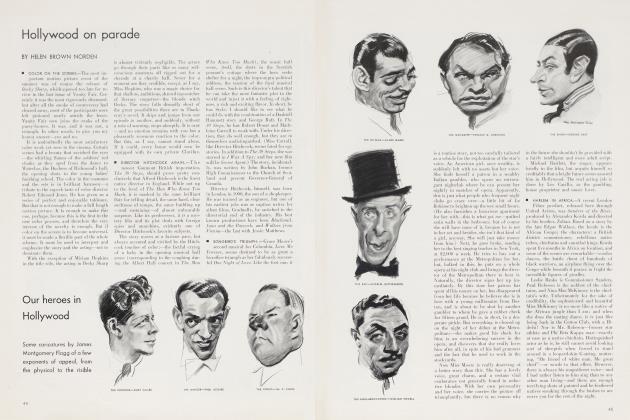

THE PATH TO WEALTH—Peggy Hopkins Joyce, a unique American symbol in her own right, apart from the Follies connotation, was a barber's daughter from Norfolk, Virginia, who ran away with a trick bicycle rider when she was fifteen. On the train she met another man. This was Everett Archer, whom she married in Denver. It lasted six months. In Washington, she met, married and divorced young Sherburne Hopkins. Thence to New York, where she met Ziegfeld.She couldn't sing.she couldn't act. and she certainly couldn't dance, but in the Follies of 1917, she blossomed forth as an American beauty. Since then, her matrimonial career —America's eighth largest industry, it has been called—is public record. To have been a Joyce consort is almost as great a badge of distinction as to have been a Follies Girl—and there are almost as many of them. At present, the lady is singularly single and has just returned from the Riviera, where she finished another book, the sequel to Men, Marriage and Me—a curious document of Americana and commentary on our cultural structure.

Peggy Fears came from New Orleans, met Noel Francis, a Follies Girl now in the Hollywood ranks, and, through her, became the youngest prima donna in the Follies. She left the stage to marry A. C. Blumenthal ("You can have your city hall, I'll take A. C. Blumenthal")—the real estate and film magnate. At present, Mrs. Blumenthal is the busiest theatrical producer on Broadway in her own name, with Music in the Air, one of the few authentic hits of the season; Party in the near offing; The Establishment of Mme. Antonia on her list: and the All-Time Follies in her mind.

Ziegfeld's stately Dolores, the best known showgirl of them all—famed for her peacock walk—is now Mrs. Tudor Wilkinson, holding salons in the Rue St. Honoré in Paris. Ethel Amorita Kelly married Frank Gould. Jessica Brown is Lady Northesk, Justine Johnston, who bore, in company with half her countrywomen, the Alfred Cheney Johnson sobriquet of ''most beautiful woman in America", now studies medicine and is the wife of Walter Wanger, formerly one of the bigger cinema magnates; Mary Eaton married Millard Webb, cinema director; and Florence Walton, once the dancing partner of the celebrated Maurice Mouvet, married wealth and lives in Europe, as does Anastasia Reilly of the lovely shoulders. Miss Walton is about to publish her memoirs.

THE PATH TO OBLIVION—Beauty contests recruited many of the latter-day Follies Girls. Such a one was Dorothy Knapp, "The American Venus". A convent girl—as what Follies Girl wasn't?—from Illinois, she came to New York to study art, was featured by Earl Carroll in his 1922 Vanities, and two years later, she was in the Follies. Later years have seen her fame confined to a series of law suits, an esoteric battle at a Beaux Arts ball, a mysteriously battered face.

One of the loveliest faces ever to bloom in the Follies was that of Imogene Wilson, the blonde "Bubbles". She came to New York at fourteen from a Missouri orphanage and entered the Follies via the posing route. Linked with Frank Tinney in what was the scandal of the decade, she went to Germany, changed her name to Mary Nolan and became a motion picture actress. Later, she returned to America and Hollywood. Her particular gift for tragedy followed her there, and she became implicated in a slander suit. Shunted out of pictures, she and her husband opened a dress shop which ended in a series of suits brought by their creditors—and eventual bankruptcy. Recently, Mary did a personal appearance tour of the subway-circuit.

Two other former Follies names have recently made news. Helen Lee Worthing of the cameo profile married a Negro doctor, whom she divorced not long ago and who is now suing her, in turn, to have the divorce set aside and the marriage annulled, instead. And Eva Tanguay, who "didn't care" in the Follies of 1919, was a month or so ago the beneficiary of a charity performance held in Manhattan.

THE PATH TO DEATH—When Ziegfeld brought Anna Held of the convex eyes from Paris, the song which made her the toast of New York was this:

"I'm fond of romps and games, you see,

I wish you'd come and play wiz me.

For I have such a nize leetle way wiz me,

I wish you'd come and play wiz me."

This was considered very provocative. (Remember, it was the "I love my wife, but oh you kid!" era.)

Anna Held was born in Paris, of Polish immigrant parents. At fourteen, she began playing tragic roles in a Yiddish theatre in London's unsavoury Whitechapel district. Later, she drifted to music-hall shows, where Ziegfeld discovered her. She married him in 1896 and divorced him in 1912. Now she is dead—and so is he—but there are many who still retain the glittering memory of her days—the story of how she chased a runaway horse on her bicycle and rescued a Brooklyn magnate pure Ziegfeld fiction -and of the times when all downtown New York traffic stood still so that Anna Held could cross the street.

Death came also to other lovely bearers of the Follies brand. Bessie McCoy, the original Yama Yama girl, died only a year or so ago. Martha Mansfield was burned to death, and rumor dubbed it suicide. Allyn King jumped out of a window; Lillian Lorraine of Blue Kitten faint' fell downstairs and broke her back; Helen Walsh burned to death last year in the explosion of Harry Richman's yacht; Olive Thomas found tragedy and death in Paris, at the time she was the wife of Jack Pickford; and Kay Laurel died in Paris, winning for her illegitimate son a substantial inheritance.

There they are—the three-score or more whose names have spelled beauty and the high life. They have swung in flower-wreathed swings out over the bald-headed row; they have draped themselves in "living curtains" against incredible backgrounds of Joseph Urban blue; they have pranced across the stage and kicked their heels to metronome beat. And, later, they have gone on into life—to sing, to dance, to act, to marry or to die. And always there has followed them that significant aura, that ultimate encomium: She was once a Follies Girl.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now