Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe gnome nobody knows

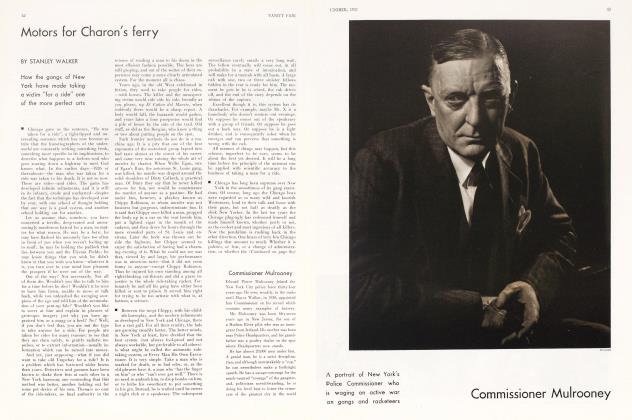

STANLEY WALKER

Louis Howe is going to be the inner-office man at the White House:—who is he, and what influence will he exert there?

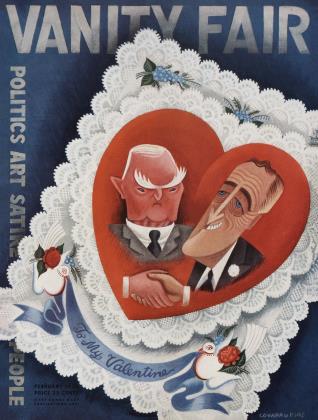

Ever since it became obvious that Franklin D. Roosevelt was to be the next President of the United States, the word-painters who write of national politics have, on drab days, attended to the building up of the curious figure of Louis Howe—or "Colonel" Louis McHenry Howe, as the more flamboyant of them have it. The election of Roosevelt is supposed to have been the result of Howe's prescience and unfathomable skullduggery, beginning on the day in 1910 when Howe first eyed the handsome young man and said: "That fellow is Presidential timber."

Howe, the long-time friend and close adviser of Roosevelt, has been described as Warwick, valet, secretary, fixer, man behind the scenes, far-seeing prophet, yes-and noman, writer of eloquent speeches, practical politician, dreamer and finder of powerful poetic allusions. The Greeks may have had a bird like him. and the Ptolemys needed one, but in modern times no one, certainly no President, has had a man of Howe's background and personality, or a man who will occupy anything like the place that this smart little introvert will fill after next March 4. Presidents have had advisers, hut none like Howe; they have had cronies, as Harding did, but Howe is no man's crony. His loyalty is not to himself, or to an abstract ideal of government, but solely to Franklin 1). Roosevelt.

When the Roosevelts go to Washington Howe, of course, will go along. According to present plans, he will not only live in the White House, as lie has lived in the Roosevelt homes in New York, Hyde Park and Albany, but he will be the brains back of the secretariat. A tired and infirm little man (lie sometimes has to pause a long time for breath when walking up stairs), he will demand of the other people about the White House the same complete fidelity which he has given to his boss for so many years. How important will he be? Certainly he will give, as he has always done, every bit of his strength and cunning to the cause of Roosevelt. How effective lie will be is another matter, for he will be moving upon a larger stage, where the action is sometimes incredibly swift and cruel, and where enemies rise up suddenly who are more ruthless than the harmless little boys one encounters in state and local political squabbles.

In the first place, Howe will be forced to deal with Congress. During the campaign Howe either lost, or failed to make, many friends, particularly among Senators who had their own ideas as to how the battle for the forgotten man should be fought. All this may be to Howe's everlasting credit, for, taking them by and large. United States Senators are not noted for being authentic thinkers. Indeed, the run of them are as pompous, bombastic and time-serving a set of ornaments as may be gathered conveniently in one chamber. If Howe offended them, then quite possibly Howe was right. And yet these are the men who must push through those bold and somewhat radical experiments in legislation which are due to bring order out of chaos and all that sort of thing.

Howe, moreover, will have to deal with the hungriest set of deserving Democrats ever turned loose on an impoverished country. Lord knows they were hungry enough when they had it, back in the days of Wilson, but now, after twelve years of Harding and Coolidge and Hoover, they are famished to the point where their manners already are disgustingly ravenous. Every politically-minded old fuddy-duddy, from the lad who thinks he helped elect a Democratic Governor in Maine to the wool-hat boy from the upper Brazos who once shook hands with Jack Garner, seeks a cut in the new administration. It may be true that Roosevelt is essentially high-minded, that he was elected by so many votes that he owes no obligations to any individual or any faction, that his spear knows no brother and all that and all that; the truth remains that he must deal with the squealing horde of razorhacks who are even now sidling up to the public trough. How well Howe can handle them, whether he can wheedle the right ones and kick the others accurately on the snout—that is a problem at which not all his favorite detective stories will be much help. As a tactician, Howe is better back in the tent, slowly plotting the strategy of tomorrow and next week and next year, than he is out in front where the firing is rapid and where the warriors, happy or not, must think instantly or not at all. He is, facing next March 4, in the position of the trainer of a prize-fighter who has brought his bruiser along carefully for twenty-two years, watching him. sleeping with him, letting him smack a few punks around for the exercise, and who then shoves him into the ring for the battle of the century. Howe will be in the corner, but the man in the ring, champion or false alarm, will be Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The truth seems to be that Roosevelt, at heart, is more impetuous than Howe. It may he a difference in their mental processes or their intuitive reactions to issues, or it may he because of Howe's ancient habit of taking things slowly, of conserving every bit of energy, of never making a fast move when a slow move would do just as well. Before election. as even before the Democratic convention. there was little need for the rapier thrust—the Republican party was through.

The closest observers of the two men (and these are the men who sat with them in their intimate debates or stood by the telephone while delicate negotiations were being carried on) agree pretty well that on several occasions Roosevelt was wishy-washy, or vague in his pronouncements, or silent in the face of a situation which cried for bold statement, simply because of Louis Howe's advice. Well, it turned out all right, and Roosevelt will be in the White House, but somewhere on the trail he left the impression that he was overcautious and not quite forthright. The question remains: wouldn't it all have turned out even better if Roosevelt had followed his first natural impulses, striking out hard when he felt like it? On a few occasions Roosevelt has shown a remarkable ability to take care of himself. The most notable time was when he conducted the hearings in the case against Mayor James .1. Walker of New York. His obvious mastery of the evidence, its implications and its complexities, enabled him to put on the soundest public performance of his life. His questions were direct and clear, and never did the unfortunate Jimmy appear more helpless than when he fumbled and floundered when attempting to make sense before the Governor. If those exchanges are the correct measure of Roosevelt, then the man really has something besides a hat and a grin. The end of Jimmy Walker, and of a whole period of New York life, was accomplished quietly and efficiently by the Governor, once he had the Seabury evidence before him. Back of that there may have been instances of timidity, of punch-pulling and cost-counting, but the curtain came down just the same.

It is next to impossible to separate the things that Roosevelt has done, and to lay part of them to Howe and the rest to Roosevelt himself. The two men have been together since Roosevelt first went to the New York State Senate from Dutchess County in 1910; moreover, it is unthinkable, so close have been their peculiar relations, that there ever should be a break between them. Howe, so far as anyone has ever observed, is totally devoid of personal or political ambitions. He doesn't care whether his clothes are pressed or not; it doesn't matter much whether people like him; he makes no pretense to being a man of large vision—the curse of the dynamic politician. He lives, as he has lived for so long, with no thought except to advance the fortunes of Roosevelt. He has taken Mrs. Roosevelt to the theater, advised her on publicity for her Vall-Kill furniture works, helped run the Roosevelt household, made things easier for the children and performed all manner of odd chores for the family.

Howe is different in that he is both an idea man and d detail man. Lying hack, his heart weak and his mummy-like head pulled down inside the highest collar seen since the days of the Duke of Clarence, he figures out the moves of politicians and thinks about what Roosevelt should do; then, likely as not. he will read of an auction and will hurry off to buy something for the Governor's ship collection. He helped work out all the subtle moves by which Roosevelt's infirm legs were kept out of the limelight; he is said to have advised Roosevelt to fly to Chicago to address the convention which nominated him; it was supposed to have been his idea to have Roosevelt and his hoys rough it in a yawl up the coast. All good ideas, giving the .impression that Roosevelt had not only conquered his long illness, which is true enough, hut also that he was, in a well-bred way, a good deal of a two-fisted outdoor man.

Continued on page 64

Continued from page 24

For all his ability, and for all his undeniable value to his chief, a great many stories are going around about the midget king-maker which are sheer hunk. Because he exclaims "Mein Gott!" occasionally, he is pictured as a whimsical fellow. Because he received the honorary title of "Colonel" from Governor Laffoon of Kentucky, the press, hoping for God knows what, tries to make the label stick. Because Howe thinks it silly, he is described as a great man of surpassing modesty —as if being one of Ruby Laffoon's Colonels was a whale of an honor. Because he once feebly deprecated the suggestion that he was "Roosevelt's yes man," he is set up as a man of iron. Because he worked on a Saratoga newspaper as a boy, and later for a time as a not very important correspondent for the old New York Herald, and was known to have a speaking acquaintance years ago with the late "Boss" Platt, he is referred to admiringly as having an enormous journalistic background, combining the best features of Richard Harding Davis and the early Mark Sullivan. Because he occupied a little office on lower Broadway once as secretary to an organization known as the National Crime Commission, and because he reads detective stories before he goes to sleep, he has been referred to as a great crime expert—not only an expert, but as a thinker with a cure for our crime problems which, believe it or not, probably will be adopted by the new administration to stop all this infernal machine-gunning and racketeering. Because he occasionally gets up enough energy to smile at some reporter's jest, the idea has got around that he has a devilishly sly sense of humor. Tired? All right, but let's try one more: because, years ago, he was heard to telephone a restaurant and order them to have a steak ready for him in twenty minutes, he has been called, by an old friend who heard it, an "epicure."

Thus we have the fantastic creation who is to be the brains of the next administration, a perfectly amazing mixture, with overtones of Colonel House, George Harvey, Harry Daugherty, Machiavelli, Frank Stearns, Mrs. Moskowitz and Talleyrand. He also reminds certain observers, in odd facets of his character, of John the Baptist, St. Augustine, most of the Borgias and Marshal Ney. He is like Napoleon because he signs his letters simply "Howe."

Not to make too many bones about it, old Louis Howe is really a very simple and ordinary sort of fellow. He eats, sleeps and occasionally visits his family at Fall River, Massachusetts. He is no fop, but that fact doesn't make him resemble Abraham Lincoln. He is not a dolt, but there is nothing very remarkable about that. He has picked up a great mass of varied and useful information, but so has Dr. Wilberforce Eames over at the Public Library. All attempts to portray him as a man who conceivably could exert the same sort of influence which Colonel House exerted during the Wilson administration must fail, because Howe is not that sort of person. He and the Colonel are small physically, and neither seeks to push himself before the public, but there the similarity ends. The Colonel looks like a statesman; Howe couldn't pass for a statesman any more than he could pass for a Tammany district leader.

Howe's qualities are simple enough, but rare. Consider his sublime faith in the future of Franklin D. Roosevelt after the campaign of 1920, when Roosevelt, to all except Howe, appeared to be that most thoroughly dead of all political figures—a defeated candidate for the Vice-Presidency. Howe said it was just as well, that Franklin was a young man, and that in a few years the time would be ripe to elect him President. Soon Howe began the voluminous Roosevelt correspondence, which he has kept up to this day. Howe would write a friendly letter to a politician or a business man in a far-off State, and Roosevelt would sign it. It merely may have asked for information, or congratulated the man on something or other, but it formed the basis for what passes in politics as friendship. That is one reason why the people, although they don't exactly love Roosevelt, vote for him in droves and believe that he is a person whose heart is in the right place.

And when the time came to gather delegates, Howe knew that the best man to act as "front" for the Roosevelt campaign was James A. Farley, the big, beaming, handshaking extrovert who is now chairman of the Democratic National Committee. Farley can write more letters than Howe; he can make a roaring speech when he wants to; he has a larger personal acquaintance than Jack Dempsey; he slaps the backs of bankers and farmers; and the Elks never tire of giving dinners in his honor. After the election, powerful Republican strategists called and reviewed the machinery of the Roosevelt campaign, admiringly, wistfully, with the tribute that the team of Howe and Farley had never made a single mistake.

Farley, of course, will be powerful in the new administration, but in all likelihood he and Howe "will continue to get along with each other.

Howe is cagey, skeptical and loyal. There are, besides Roosevelt, probably six persons on earth whom lie trusts —to whom he would tell everything, including his opinions of people and the low-down on political chicanery. He will have some of these six working for him in Washington. If steadfastness of purpose were all that mattered, it will still be the machine that never makes a mistake.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now