Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTammany Judge: Peter Schmuck

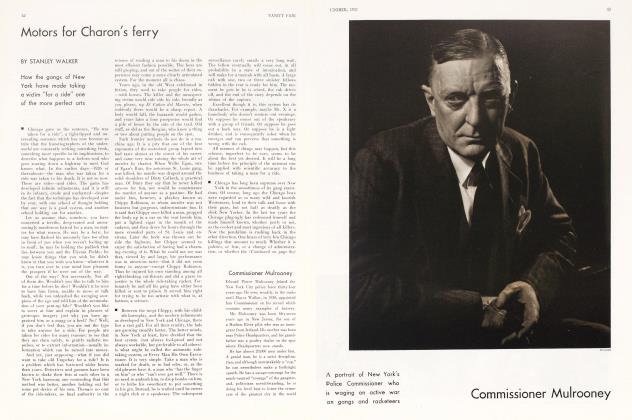

STANLEY WALKER

Justice Peter Schmuck of the Supreme Court of New York is a triple-threat judge: he isn't ignorant, he isn't crooked and he won't disappear. He is neither a pettifogger, a Dogberry nor a Crater. He has done his best to combine the best features of Demosthenes, Carlyle, and Cardozo and still remain a good Elk. He has points of similarity with all three men. Demosthenes, the Greek rabble-rouser, had an impediment in his speech and practiced with stones in his mouth; Schmuck lisped badly (still does somewhat) and, as a youth, walked up and down Broadway declaiming to himself. Carlyle could deliver himself of the most appalling mass of highflown verbiage; Schmuck's written decisions and spoken sentences outdo the Master at his best. Cardozo is known as an able judge who writes decisions which are interesting even to the layman; Schmuck is a pretty fair judge whose decisions are not merely interesting but downright entrancing.

One of the best of the Tammany judges, Schmuck exudes kindness to all, but he won't stand for any monkey business with the court calendar. He is a tough judge, but fair. He gets reversed a lot, but he knows law. He can memorize whole pages at one reading, and always could. Moreover, he is, as he says, "gregarious". He is the funniest and most popular judge in New York. Any occasional depreciation of his talents by his colleagues on the bench may be laid either to small-mindedness or jealousy.

He became a judge because he was amusing. It was in 1906 that Destiny put her finger on him. The Democratic State Convention was meeting in Buffalo. That was the year the Democrats nominated William Randolph Hearst for Governor. Schmuck, a young lawyer from Peter J. Dooling's district on the West Side of New York, was a delegate. Charles F. Murphy, leader of Tammany Hall, had a room on the fourth floor of the Hotel Iroquois. Schmuck and some of his pals, fun-loving young roosters from Hell's Kitchen and from John F. Curry's district farther north, were on the tenth floor.

One night Schmuck and his friends went to a burlesque show at which was sung the Garlen Haus Song, that inane, repetitious, German masterpiece which, in one form or another, survives today in the restaurants of the Yorkville section, though it is usually known now as the Schnitzelbank. After the show Schmuck (the man was a card even then) and his boy friends got a blackboard, a pointer, and all the other paraphernalia necessary for the proper rendition of the great song. They paraded through the lobby and the corridors of the Iroquois.

Boss Murphy saw them and was fascinated. He was particularly taken with Schmuck, who had a fine rousing barytone and whose lisp, when he sang, was not perceptible.

A little later the time came for Murphy to make up his entire slate. There was a vacancy on the City Court bench. Murphy called Dooling and said: "All right with you if we put up Schmuck? You know, the funny young man with the owlish face who sang that song at the convention." Of course it was all right with Dooling. He was nominated and elected, probably the only man who ever sang himself onto the City Court bench.

As a judge he worked hard, and eventually became Chief Justice of the City Court. Often he was mentioned for the Supreme Court, but this promotion did not come until April, 1928, when A1 Smith, then Governor, appointed him to fill a vacancy. All his life Schmuck's friends have known of his gifts of phrase-making, but it was not until he was on the Supreme Court bench that the public began to appreciate the astounding gifts of the man.

Today he is recognized by everybody. He has made his place in the hearts of his fellow-townsmen as the most amazing stylist ever to hand down a decision, or to make an after-dinner speech, in these parts. Able judge, conscientious worker, homelover, almost fanatical bookworm, stickler for ethics, loyal friend and good golfer— Schmuck is all these, of course, but it is as a master of loop-the-loop prolixity, the high priest of the art and mystery of litigiosity and ponderosity, the dredgerup of long forgotten goofy adjectives and Elizabethan nouns, that he gets a leg-up on immortality.

For him, the English language is not only art, but fun; not a blunt instrument, but a whole orchestra, or the Liederkranz going full blast.

His erudition mystifies and awes the boys at Tammany Hall. His more glowing passages are a source of wonderment to the other judges who, though bright enough fellows in their way, often have a cloddish, pedestrian manner of expressing themselves. Sometimes, in his speeches, the Schmuck lisp mars the beginning, but disappears as he warms to his theme. At other times he deliberately (he is a sketch) puts on an exaggerated lisp or thickness of speech which never fails to panic the listeners.

In his decision he sometimes, impishly, when least expected, brings up a word that sets the lawyers back on their heels. He once denounced a man for driving around New York in a "gaily caparisoned" automobile with a "blonde doxy." The boys didn't know until they went to their dictionaries that a "doxy" was a wench no better than she should be. Schmuck is practically infallible on his citations; in his quotations he makes Bartlett, the great phrase-monger, appear as fumbling and even forgetful.

One of Justice Schmuck's most famous decisions was in the suit brought against a magazine by the Shuberts, who asked $150,000 because the magazine had said that, as theatrical producers, they were "lousy." Excerpt:

"While the court agrees with the plaintiff that the statement in defendant's publication was not intended as a compliment hut rather an attempt to invite and create a derogatory estimate of the plaintiff as a theatrical producer, yet the law has not yet reached the Utopian state where envy and acrimony are penalized. The statement that a person is 'lousy' in his engagements and endeavors, meaning that his efforts are not commendable, but rather inferior in result and on the whole subject to unfavorable criticism, is not libelous per se nor libel at all."

Continued on page 64

Continued from page 41

Justice Schmuck tries many divorce, separation and alimony actions. He is a champion of the home and he upholds New York's strict marriage laws. Once, in 1932, however, he caused much excitement by giving a man a break. It was a separation case; the husband's income had shrunk; the court told the woman' that she was as much to blame as the husband for the ensuing discord. Excerpt:

"The plaintiff, obviously disappointed in the realization of her dream of social preeminence, and unable to patiently accept her fate, stirred the fires of discontent and kindled the flames of disagreement, disgust and perhaps hate by constant slur, unceasing irony and sentiment-destroying nagging. The defendant, being but human, had his limits of patience, and, devoid of the complacency of Socrates, broke under the strain, forgot his solemn promise to ever love in storm as well as in sunshine, and crossed his sword with the rapier of his wife in marital discord. Peace fled in terror, and discord chortled, in sole possession of the household."

The Justice likes to try cases involving literary works. When the wife of Ludwig Lewisohn sued the publishing house which had brought out his hook, Mid-Channel. Schmuck, in deciding against a motion to dismiss the libel action, wrote:

"The book is libelous per se. To defame the capacity of a woman for wifehood, to continue her ability to live in amity with her husband and unfavorably to compare her with another are to humiliate her and, if untrue, to unjustly subject her to intolerable ridicule. Although for the most part the book is the gibberish of a selfish sentimentalist and as excerpts quoted in the complaint indicate the feverish exaltations of a perverted and disappointed conceit against an individual in particular and society and law generally and cannot seriously affect the opinions of rational individuals, yet since the words are patently libelous per se and obviously refer to the plaintiff despite the adroit generalities used, and because a publication is made at the publisher's peril and risk, the motion is denied."

In another decision occurs this remarkable passage of understatement:

"No doubt can be entertained as to the defendant's cruel and inhuman treatment. Abusing a wife in the presence of others, invidiously criticising her as an omen of bad luck, continually commenting on her personal appearance and climaxing ill treatment with a kick in the stomach is sufficient to satisfy the law of the impossibility of achieving that amity so indispensable to proper marital relation."

Again, describing a husband in a divorce case, he said: "Surly, selfcentered and indulging, lacking in consideration and vicious to opposition, his absence would appear more desirable than his presence." Another

celebrated case involved the whiskers of A1 Hershfield, "the cartoonist. A magazine, Variety, had said that before Hershfield grew a beard he struggled without success but that "once his boyish face became a landscape he began to click, to get commissions." Hershfield sued for libel, and Justice Schmuck denied a motion to dismiss the suit. He held the case for trial, and eventually, before Justice Miller, Hershfield lost. Schmuck's memorandum denying the motion to dismiss follows:

"Plaintiff justly offended by defendant's reflection upon his right to enhance his personal appearance sues for libel asserting that the defendant intended to hurt, injure and prejudice him in his chosen field of endeavor as a commercial artist by holding him up to ridicule. The defendant spurns the plaintiff's contention claiming that plaintiff fails to indicate any special damages and that charging wearing of whiskers is not libelous per se. Ordinarily the expression of opinion concerning another's appearance may not he the subject of an action for slander or libel and yet if done maliciously and with intent to hurt and ridicule . may cause actionable injury. A calm, complacent and impartial perusal of the article in question can result in only one conclusion that the defendant intended to create merriment, vicious and unfeeling glee at whatever cost plaintiff might be compelled to bear. Undeniably plaintiff could satisfy his desire to improve his personal appearance by any manner appealing to his artistic temperament without incurring the danger of being the butt of ridicule by a description as derogatory as that of the defendant's. While the right of free speech permits of honest criticism it may not be used as a shield to justify unwarranted and unnecessary insult."

Peter Schmuck was born in West Thirty-ninth Street, between Eighth and Ninth Avenues, in a house which has since been replaced by a loft building. His people came from a little town in Germany called Bingen-on-

Peter was graduated from the College of the City of New York in 1893. He got his M. A. from Columbia in 1895 and bis L. L. B. the following year. In 1893 he was elected manager of the baseball team, and hordes of students went out for baseball that year, not because they thought they could make the team but because they wanted to be near Peter. He liked athletics of all sorts, but he was no athlete. He liked, most of all, to astonish his fellows with his feats of memory. He was a good student.

His first law partner, when he hung out his shingle at 35 Nassau Street, was John J. Graham, who later became Surrogate of Nassau County. From then on he did fairly well, and then came the Buffalo convention which gave him the chance to make himself famous with the song.

Everyone thought Peter Schmuck would marry young. There are tales of a baron's daughter in Germany, and of how Peter's grandfather hoped for a marriage between them. Whatever the truth of this, Peter, known as strictly a man's man, did not marry until 1916. In that year he married Mrs. Millie Manovitch (nee Stitch), who had been divorced from her former husband. The ceremony was performed in the Church of the Strangers. Peter, who is religious by nature, frequently attends the church where he was married, and sometimes takes the pulpit. He and his wife live at 270 Park Avenue. They have no children.

Continued on page 66

Continued from page 64

Justice Schmuck has lots of fun. He rarely goes to the theater, as he says his courtroom is reeking with drama. He has lunch every day at the same table in Haan's Restaurant, downstairs at 290 Broadway. He eats practically anything within reason, and smokes fifteen cigars a day—any brand. He likes to play golf at the Westchester Country Club, and shoots between 90 and 95. He is president of the City College Club, an organization of alumni, and he probably can hold that office as long as he wants it.

Justice Schmuck carries himself erect, with his chest stuck out. When Dr. John H. Finley was being inaugurated as President of City College they called upon Schmuck to deliver the Ephebic Oath. Someone called him at his court and asked what size gown he should have, "38 or 40." Schmuck roared, "What do you think I am—a pewee?" He holds his shoulders well hack, and can look the part of a benevolent German field marshal. He is proud of his energy and his iron constitution and sometimes tells his friends that death, he thinks, can come to him only through some "unnatural cause"—perhaps a miracle, but more likely some sort of accident.

He gave up drinking and going to cabarets when he went on the bench. After all, a judge must be dignified if the people are to have proper respect for law.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now