Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

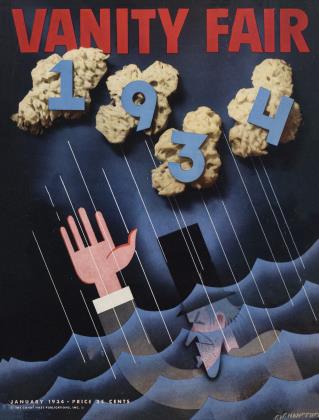

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe wettest New Year

STANLEY WALKER

New Yorkers will remember the last night of 1933 as the wettest in the city's history. Even the boozy high jinks of the pre-war period will probably appear, to the old timers who remember them, as extremely sedate and dull. This New Year's is. for all practical purposes, the dawn of that new freedom of which all good livers have dreamed ever since the cold night of January 16, 1920, when National Prohibition went into effect. To he sure, in some States drinking is still illegal, or hedged about by restrictions almost as had as the prohibition law, hut the battle is won.

Even before Utah came through with the deciding vote for repeal, the larger cities of America were almost wide-open. The wetness increased steadily, so that by December 5, the date of the convention which settled the last technicality, New York, in particular, was dripping. For two months the New York hotels have been reporting better business. The speakeasies and night dubs have been fuller than at any time since before the crash of 1929. It is possible that a part of this boom has been caused by the spirit of inflation, by the feeling that the dollar is going to be worth even less and might as well be spent at once.

With the ordeal over, it has been comforting to know that one may drink legally with one's fine-feathered friends in the Sert Room of the Waldorf, alone under the cool stars, or all night long with cronies in your own house. Stomachs lacerated by almost fourteen years of gin and inferior whisky are feeling once more the soothing effects of wine. The silver has been polished, the glasses put in order, and books on wine have become best-sellers.

The American (particularly the New Yorker) seems almost happy again, and the horrors of economic distress have become bearable. The country is filling up with charming foreigners—from England, France and Italy especially—who find that they can live about as cheaply here as abroad—a reversal of the economic trend which followed the war.

Moreover, we are told that the American is to have another chance to behave himself, a chance, even, to emerge from the barbarous customs of the twenties and to have another try at being civilized.

They tell us now that we have won a great fight for freedom, that tolerance is in the air again, that decency is on the way back, that graft and thuggery are to decline, that the wells of dirty money are drying up and that even temperance seems probable.

But it may still be suggested that the era of maximum happiness, law and order may not be here after all. In many states there will be little or no legal drinking; in others the rules are outlandish. There have been few signs, moreover, of the moral regeneration of our low-bred and swinish criminal element. The trimmings under the new dispensation will he different, and the technique must change somewhat, but it is probable that the racketeer, or whatever we choose to call bis successor, will look with just as lascivious an eye upon liquor money as he did during the years of the great experiment.

What now, Big Shot? You may be driven to a complete change in your line of attack, but we cannot believe that the end of prohibition will mean your utter ruin. A1 Capone, being in prison, not for violating the liquor laws but for evading payment of income taxes, cannot, for a long time, hope to come out and reorganize his empire in order to meet the new conditions. But his successors in Chicago are already busy.

In New York the members of the school of Irving Wechsler (Waxey Gordon) and Arthur Flegenheimer (Dutch Schultz) will continue their fight for existence. They fought a brave battle for our liberties—a costly one for the consumer, to be sure—during the dark days, and they may figure that they deserve some public gratitude.

Other men commonly associated with the bootleg liquor interests, notably such entrepreneurs as William V. Dwyer and Owen Madden, are of a type which has enough sense to make a living without circumventing the law. They have not announced their plans. Although both men have prison records, they have enough character to run a decent restaurant or club. Below them come the riffraff, the hangerson, the tatterdemalion army of leeches, rats and chiselers to whom an honest dollar for honest work is a contradiction in terms. Already we have large restaurants, serving both food and liquor, which are owned ostensibly by reputable persons, with one or more ex-convicts having a "piece" in them. This "piece" system was the curse of the ownership of everything, from low dance halls to the highest class of night clubs, during prohibition. There is no way known to law or science to stop it entirely.

The racketeer may not be a statesman, but he is not always a fool. The Big Shot knows very well that he doesn't have to work at an honest trade. The police know this, and so do the conscientious gentlemen who are trying to frame the regulations for the control of hard liquor. One of the ablest members of the New York board says: "We'll do the best we can, but it's going to be a mess."

A pious slogan of such well-meaning and public-spirited men as John I). Rockefeller Jr., who helped (mistakenly) to take our liquor away long ago and who now, with all good will, tells us how we should drink it, is to the effect that the profit must be taken out of alcohol. That profit has not yet been taken out, nor can it be entirely.

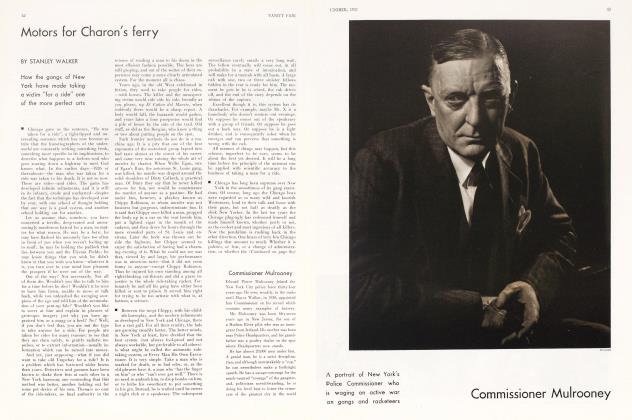

The regulations for the sale of liquor as announced by the New York State Alcoholic Beverage Control Board, of which the philosophical and realistic Edward P. Mulrooney is chairman, appear to he by far the most sensible, complete and liberal yet devised.

(Continued on page 54)

(Continued from page 39)

Briefly, the new liquor rules in New York provide that: (1) places serving liquor for consumption on the premises may remain open until 3 a.m.— which is surely late enough for most people. (2) Liquor may he served in licensed places where food may be served, hut the drinker doesn't have to eat. (3) No one may he served hard liquor at a bar, but must sit down to drink: the drink to be brought by either a bartender or a waiter. (4) Liquor stores, where liquor may be sold to be taken out, will remain open until 8 p.m. and will be placed not closer together than 1,500 feet. (5) Liquor must be sold in, or served from, original packages—a regulation designed to prevent the bartender from cutting the liquor from a barrel or keg, a practice which used to he the regular Sunday morning work of the old saloonkeeper who liked to gyp his customers.

With the announcement of the new rules, there has come general but far from universal approval. The rule against stand-up drinking at bars, in particular, has aroused an army of fanatical vertical drinkers who had assumed that with the repeal of prohibition they could grab one, two or more "quick ones" at the bar and then walk out without going to the trouble of relaxing at a table. These drinkers have pointed out that they had been accustomed to drinking at speakeasy bars all during the prohibition period; therefore the new rides, far from indicating the dawn of freedom, really are worse than prohibition.

The bartenders, too, are not pleased with the rule which deprives them of the close companionship of some of their most entertaining customers. Theirs will he a lonely life. It is well known that the alert and diplomatic bartender, engaged in his pretty art through the years, absorbs by a sort of osmosis, an amazing lot of useful information. Some of these old bartenders are as crammed with facts as the World Almanac, and are just as handy at settling barroom bets as that excellent and exciting work. To tell them that they must stand in monastic loneliness, mixing drink after drink in silence, is to condemn them to a barren, intellectual life. Not only will it interfere with the spread of human enlightenment, but the bartenders will become morose and even bitter. More, it will work a hardship upon many drinkers, to whom the privilege of talking to a bartender has about it some of the relief which other men get from the confessional.

Another matter which puzzled the hardened bar drinker when the Mulrooney rules came out was the realization that he had been betrayed, as he felt, by his ostensible friends. In making up the rules the hoard called upon the combined wisdom of many different men and women. The drys, of course, were not much help, for, sad as it may seem, the professional and convinced drys devoutly hope that conditions will become as messy as possible.

The four men, according to inside information, who were responsible for the chair drinking edict were, reading from left to right: Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler, president of Columbia University, whose stirring speech against prohibition before the Missouri society in New York in 1924 was the first powerful and effective blast from such a highly respectable quarter; Alfred E. Smith, the growling and splenetic old warrior; James W. Wadsworth, who once lost his seat in the United States Senate because the up-State New York Republicans thought that he should at least give lip service to the dry law, and Jouett Shouse, who, as head of the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment, finished the fine battle of propaganda which was started, back in the dark days, by Captain William H. Stayton of Baltimore.

(Continued on page 55)

(Continued from page 54)

The New York hoard simply could not laugh off the combined argument of those four noted wets. Those men said that bars meant saloons, and if they were allowed to return, the old declaration of the wets that "of course, we must never have the old-time saloon back" would he nailed as so much moonshine. The drys are always waiting in the shadows, ready to pounce upon the newer and handsomer John Barleycorn. They are eager to revive their old stories and pictures—the drunken mothers who crush the lives out of their babies by rolling on them fa habit which is said to he very had in parts of England) the husband ruined and broken by the wheedling call of "just one more," the blowsy crone in the back room, the mother with the frail child clinging to her skirls waiting for daddy to come out of the ginmill. These and all the other horrors and tear-jerkers, real and imagined, have been paraded by all the drys from John B. Gough to Billy Sunday.

Mulrooney himself, certainly before he listened to the cautious counsel of the Elder Statesmen, was inclined to favor drinking at bars. As an old policeman, who knows bis New York and understands, as few do, the temper of its people, lie believed in bars, but be finally voted with the other members of the hoard to give the sit-down system a chance.

Will it work? I don't know.

One eminent judge says the rule is silly, and that the rule is sure to be violated widely; another judge says that Mulrooney was unfit to handle the liquor problem because he doesn't drink, and only a drinking man can understand the fine points of honor, of appetite and custom of the drinking man. However, such men as Nicholas Blair of the Paradise, George I.amaze of the Park Avenue Club, and James (Dinty) Moore are enthusiastic over the elimination of bars for hard liquor. These three men form an almost perfect cross-section of the better class of sensible and long-headed purveyors of food and entertainment in New York.

Not to heat about the bush, or to asperse a sex which deserves many of the pleasant things said about it by the poets, the truth is that the behaviour of women during the prohibition era. has been as much as anything, responsible for the rule. On the night of January 16. 1920, a reporter for the New York World set down, with apparent astonishment, that he bad observed a young woman taking a drink at a bar in New York. It was puzzling. But, after a few years the women, and the ladies too, swarmed all over the place. They loved the cute speakeasy bars, whether standing up or sitting at the little stools; somehow it represented a victory for their sex like riding a spirited horse, or smoking a cigar. Well, the girls are now howling loudest of all at the no-bar rule. Dinty Moore, who has known his New York for more than forty years, on being asked his opinion, said:

"Great! I wouldn't want a bar in my place, for men or women. If women were allowed at bars, after drinking is legal there would be a murder a night. A bar is something for a longshoreman to drink beer over."

Can all of the New York regulations be enforced, even to a reasonable degree? Probably not, but if the 20.000 New York police put their minds to it, the new rules can be enforced more easily than the old prohibition law. The penalties, involving loss of license, are serious.

How much of a mess the new deal in drinking will prove to be is a matter that has even the long-range prophets puzzled. But of this much we may be fairly certain:

There are still many bootleg joints in New York, and they will not he wiped out for many a day.

Already there are stories of favoritism and pull in the obtaining of licenses. There will be more of this sort of thing, together with ugly stories of political graft.

There will be charges, and some of them will be substantiated, that the old, infamous tie-up between distillers and brewers and the retailers has not been broken down.

The drys, moreover, can find evidence, if they look for it, that New York's "no credit" rule is widely violated; for many a drinker will still put it "on the cuff."

The liquor interests, even in the short space since repeal, have found that they still have some use for "muscle men" and racketeers. Indeed, the racketeering system is so well intrenched that even the most respectable business is likely to have a trace of it.

In some parts of the city unlicensed liquor flats, ostensibly private homes, have led to a system of bootlegging (and in some instances, to prostitution) which the police will find it difficult to control.

There will be stories that the inspectors of the beverage control board are not as high-minded as they might be.

The liquor lobbies, the brewers' lobbies, the hotel men's lobbies, and all the rest of the special interests, are preparing to make just such fools of themselves as they did before prohibition.

There is still a strong dry sentiment in the country, and in New York the upstate legislators, who dislike New York City anyway, will attempt to make the rules more rigid. It is possible that the Slate may have to take over the whole business.

There will be an increase in drunken automobile drivers. Indeed, in many sections the legalization of 3.2 per cent beer, despite the fervent hopes of the wets, resulted in an increased number of automobile accidents.

It will be impossible for the Federal government adequately to protect those States which wish to remain dry. There will he charges that the government isn't trying, and stories of the corruption of State officials by bootleggers.

It will be impossible to take all the profit out of booze. There is still big money in it.

But life in New York, for a time at least, is going to be a good deal pleasanter—and more exciting. But—the drinkers had better be good while they have their chance. ,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now