Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe women's magazines

DORA COPPERFIELD

EDITOR'S NOTE: This article is the last of a series discussing various types of American magazines; it has been preceded by papers on the pulp, the movie, the quality, the liberal, the humorous, and the little periodicals. As might be imagined, "Dora Copperfield" is a pseudonym of a woman writer.

LADIES—JUST LADIES.—They stare at you from the covers—the bright-eyed babies, immaculately conceived, or the sweet smart girls, provocative hut pure—and underneath. the great big Names that feed the great big circulation which insures the fat content of the advertising. These are the women's magazines, the most powerful group of periodicals in America, in the sense that they are the most far-reaching and claim the greatest degree of intimacy with the daily life of their readers. Even in these lean-wallet days the combined circulation of the Big Five alone IWoman's Home Companion, Pictorial Review, McCall's, Good Housekeeping, Ladies' Home Journal) chalks up comfortably over the ten million mark; and these figures must he increased and multiplied considerably to gauge the number of readers thus exposed.

These periodicals, of course, trace their descent directly to the Lady's Books of the Eighteenth Century and in many ways they still resemble their grandmothers. In the pre-natal stage they were the papers addressed to the Sex by Dr. Johnson and Addison and Steele, those blends of curtain lectures and faintly condescending gallantry characteristic of the era of didacticism.

Some such idea was translated into the American by Benjamin Franklin in his General Magazine founded in 1741. Four decades later we find the female section of the reading public being actually singled out and solicited by the Gentleman and Lady's Town and Country Magazine which protested, almost too much, that its purpose was "rather to please than to wound Woman, the noblest work of God." God's masterpiece was accordingly pampered with heavily sugared love tales, rebuses, enigmas, a Blossoms-of-Parnassus-Department, and such starch as was to be derived from essays entitled "Desultory Thoughts on Encouraging a Degree of Self-complacency Especially in Female Bosoms; Rules and Maxims for Promoting Marital Happiness" ("read frequently the marriage ceremony, not overlooking the word Obey . . . remember that the person with whom you are to spend your days is a man not an angel . . . and not to dispute with him, be the reason what it may . . .").

By the close of the century the feminine literary rib had been excised from Adam's side and the first frail lady's magazines stood alone and unchaperoned. The most elaborate of the breed was The Lady's Magazine and Repository of Entertaining Knowledge, a handsome octavo of no less than three hundred pages which preferred the semi-annual form "so as never to be stuffed with that outworn and disgusting phrase To Be Continued." It boasted an elegant frontispiece depicting the spirit of Lady's Magazine accompanied by the Genius of Emulation (with laurel wreath) kneeling and submitting to Liberty a copy of the Rights of Woman (nothing to do with suffrage but with the perquisites of the accomplished Female—love of religion, patience, fortitude, etc.) The one exception to the general sofa-and-smelling-salts atmosphere was The Lowell Offering, a woman's rather than a lady's publication, which suddenly came to life under the smoke stacks of Lowell, Mass.—a six and one-half cent sheet edited entirely by the mill girls of the town and dedicated to the daring proposition that "Working Hands might have Thinking Minds." It was a biological sport and died without descendants, whereas the Lady's Books lived to beget, quite without sin, the three successes of the Nineteenth Century which set the pattern for today.

GODEY AND AFTER.—These three were, of course, the Ladies' Companion, Graham's, and Godey s, the last two owned by the redoubtable Mr. Godey and the first soon swallowed by the third, thus leaving him sole monarch of the field. And he knew how to fertilize it. Godey was the first of the go-getter publishers in the periodical world. In the editorial sanctum, he installed the very genteel Mrs. Sarah Josepha Hale—in black silk with a fall of lace, sweet, a little sad, more than a little smug.

Mr. Godey, with his manly aggressiveness, busily launched the first strident magazine-pushing campaign. With the shekels that rolled in, he promoted that other cardinal modern policy of Big Names, which so prolifically induced still bigger circulation. What if William Cullen Bryant shook his bearded prophet's head over the dangers of so wide a reading public? He, like all the other illuminati. wrote for Godey. Longfellow, Hoffman, R. H. Dana, Osgood, Cooper, they all lined up for a share of the Godey gold. Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe, it is true, stoutly deplored the practice of poets and essayists elbowing in among the fashion plates. Poe, resigning as editor of Graham's, raised a roar of denunciation of "the namby-pamby character of these magazines with their contemptible illustrations, music, fashion plates and love tales."

But Godey went marching on. The words of P. Cooke penned in 1849 have a contemporary ring. "Magazine articles," he wrote, "derive nine-tenths of their value from great or famous names: Longfellow's worst poem is preferable to my best." Other modern policies developed. Departments. We find the Fashion Editor taking orders for making the hair of the beloved into beautiful brooches and bracelets. Orders were also filled for purchasing bonnets in towns; model cottages were shown, Mansard or Swiss horrors; prizes were offered for writing the best essay on "What becomes of the pins?"

The period, remember, is that of the Civil War, the years preceding and immediately following. Women are pioneers on a hundred fronts . . . but you will find no trace of this in Godey's. There is no expression of the heroic age in these pages peppered with hydro-cephalic creatures of romance. Into Godey's no draught is allowed to blow to chill the circulation.

Dedicated to a similar proposition, now arose the Home Companion (afterward the Woman's Home Companion) and the Ladies Home Journal founded in 1883 by Cyrus Curtis and edited for a time by his wife under the name of Mrs. Louise Knapp. The ascendency of the Journal, however, occurred with the advent of Edward Bok, the second big name in the story of this little Lady's Book world. Bok. like Godey, was an innovator. Bok made of his magazine a genteel back fence, where gossip was given and received in a pleasant girl-to-girl manner. He likewise introduced the god Glamour. He was the father of the ubiquitous Personality Article. He flavored the sweetness with the spice of intimate tales of the great—Famous Daughters of Famous Men; the Duchess Tells Her Personal Story, etc. . . . Bok also exerted a major influence on the aesthetic taste of the country. He launched a vigorous campaign for adaptation of the colonial and early American styles which soon resulted in that flood of vine-covered cottages with ruffled curtains, at best wholesomely plain and at worst bedizenedly cute. The gospel could have been far more pernicious, but it did succeed in retarding the creation of original native styles. Until very recently no modern innovations in the field had a showing in the women's magazines, and the most powerful impetus came only from the Century of Progress.

This conservatism is characteristic and all-persuasive. "We need material," say the editors of these magazines. "All kinds of material that is human and will interest women. . . . Of course, steer clear of Sex unless it is sweet and romantic. Not too much realism—none of that school of open plumbing openly arrived at. And, of course, avoid controversial subjects—in the field of economics or sociology. As for religion, lay off that entirely. . . . Have you any sparkling young love stories, clean, with happy endings? But let us see what you have. We need new blood in the magazine."— But not unless it is the right shade— let there be nothing off-color.

(Continued on page 53)

(Continued from page 23)

FEMALE MAMMOTHS.—Two twentieth-century tendencies, however, have modified the line of evolution. One is the mighty force of advertising. The women's periodicals have weathered the depression with the fattest hulk of advertising of all the magazines, for are not women the nation's buyers? Where advertisers had to choose a single mast to cling to, they clung to the woman's magazine.

And it has been a comfortable mast, it has supported them well—not merely with changed formats but with solicitous touches in the reading matter. No longer, for example, in many of these magazines does our hero toss with overwrought nerves due to a too generous shot of coffee. No more does the fictional housewife complain of frigidity in her oil burning system. Nor have stenographers and office boys a monopoly on gum-chewing; recently a well-known chewing gum firm communicated with the editor of one of our leading female publications, insisting that he wanted Nice People shown chewing gum as well.

Nor is this all. The force of advertising has pushed Nice Nellie of the women's magazines out of her position in the center of the stage; for where her delicate sensibilities were always unique in the editor's mind, he has now the sensibilities of the advertiser to consider. For example, there was the famous Intimate Hygiene Campaign. Was this not going to he a feather stuck in Nice Nellie's throat? With gingerly dignity the thing was dared and done—not without hoarse and bitter cries from Nellie. Nellie had to be taught with care to take it and like it; and she was. Followed the War of the Cigarette ads, the final shot of which has only recently been fired by the last die-hard editor who publishes essentially for the whalebones of the nation. When the first issue appeared showing a lady with a cigarette in her genteel fingers, this editor waited somewhat breathless. But only eight letters of protest appeared to haunt him; yet now the big Beer and Liquor War looms on all fronts. Ella Boole and her stout cohorts of the W. C. T. U. may have failed politically, but they still read the women's magazines.

Yet the day of the Vestal is passing, and the women's magazines know it. Enter a faster tempo, a let's-go spirit; stories began to whizz like cars, shiny, snappy. Quips, wisecracks, trick titles. (A tale called "Buyer in the Ladies Wear" appears as "One Knight Off"; an article on coiffure becomes "HairLines Limited.") Nellie reaches out toward sensationalism—just a little bit and in a very nice way. Murder is now allowed, provided it is not too sordid or pathological. The young girl with the nails of fire-engine red is found acting a little giddy, but be assured that she will learn better in the arms of the handsome two-hundred-pound tackle, an All-American type, essentially like Father under his football shirt.

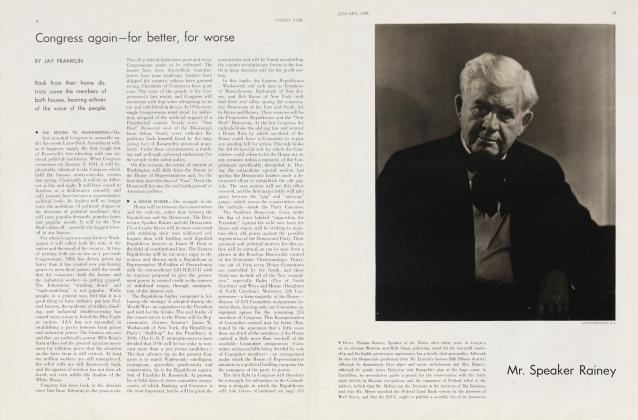

DIFFERENT—YET THE SAME—This then is the peculiar blend, as we find it, of sugar and spice and all things nice, which is what little girls are made of. The proportions of the ingredients, of course, vary with the personal equations of the editors. One faction, for instance, is more progressive than the other: Delineator and Pictorial Review cater somewhat more to the younger element than McCall's or Good Housekeeping. Again the emphasis on articles or fiction varies. In Good Housekeeping you will run across numerous items of non-fiction, enlightening or inspirational; its editor, William Bigelow, a veteran in the field who enjoys a solid oak reputation for reliability and doctrinal sincerity is, and has been for many years, a Sunday school superintendent in his community and prints his book with the stamp of his personal convictions. The publisher behind him is William Randolph Hearst. . . . The Ladies' Home Journal similarly reflects the philosophy of George Lorimer; Mr. Loring Schuler, high-powered, grave and gentlemanly is the chief of staff.

McCall's, on the other hand, are not found poking their noses into such socio-economic essays: they specialize rather in the romantic touch and sentimental fiction ("Love Is Found in the Young Old Way and a Dream Dies at the Dawning.") The editor here is a young man, Otis Wiese, for some years known to the magazine world as the Boy Editor. Mr. Wiese, with the dew of the university still fresh upon him, stepped straight into the chief editorial chair, whence he has steered the magazine to unprecedented heights. He has increased advertising and circulation; he has dressed his book in a snappy new format, leaving the old conservative content untouched except for a few minor innovations.

However, just as McCalls is now forging ahead, it is equally true that Pictorial Review once led the field not merely in adult quality of fiction hut in circulation. This was in the days of the late, beloved Arthur Vance, who was deeply fond of good writing; after him the accession passed to Percy Waxman, a writer and critic, who sought to carry on essentially this tradition, according to his lights; now the magazine has changed hands and is directed by Mr. von Ziegkursb, erstwhile of a Philadelphia tabloid paper and the pulp magazines. He aims to enliven the magazine. He is assisted by the extremely able Miss Helen Walker who has been there all along, constantly serving the cause of an intelligent broad-scoped policy. Incidentally, here is an. interesting point to mull over in one of those metaphysical moments. The woman's magazine field is full of women editors but, save for one conspicuous exception, they are all in subordinate positions. Very often—and this is also true of other popular magazines—it is these women who are for printing the new or daring, that "different" story, that article that is controversial, the piece the men call too "hard hitting." One speculates on what would he the flavor and fate of a magazine actually run by women instead of merely for women.

(Continued on page 54)

(Continued from page 53)

It will not serve to turn to the Woman's Home Companion for an answer. It boasts the only woman chief, Miss Gertrude Lane, who, the story goes, was a librarian until she climbed straight to a high place on the Companion ladder and a few years later fabulously found herself Vice President. Her social mindedness is revealed (safely) in her editorials. The selection of fiction is in the hands of an editor from Collier's and shows his influence. Miss Lane is surrounded by a masculine directorate of the Crowell Publishing Company and by a bisexual staff. She is, moreover, a recondite editor whom it is hard to see. One remains uncertain of the exact weight of her influence. In this field, of course, the power of fundamental policy overshadows individual editorial tastes. Thus, for some time Theodore Dreiser was able to serve as editor of Delineator without any especially revolutionary effects on this book or history's annals. His seat is now occupied, no doubt more comfortably, by the pleasant Oscar Graeve, a genial light writer in his own account, who conceives the function of his publication as rather to amuse than to play the mentor.

Few women's magazine editors will deny that there exist women with mentality sufficiently tough for more muscular fare than is currently served. They frequently in fact throw these readers a bone, among the Sparkling Love Tales and the Throbs by Temple Bailey. More than this they are unprepared to do. They are not going to toss at night worrying about the law of diminishing box-office returns. In these times, they tell you—yes, and tomorrow—we cannot take a chance; and it is essentially safer to cater to the lady primarily interested in setting her table, comme il faut, even if the world shakes under that table.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now