Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHow unlike we are!

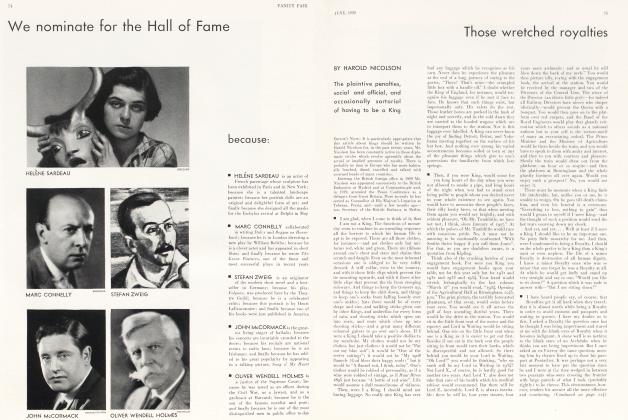

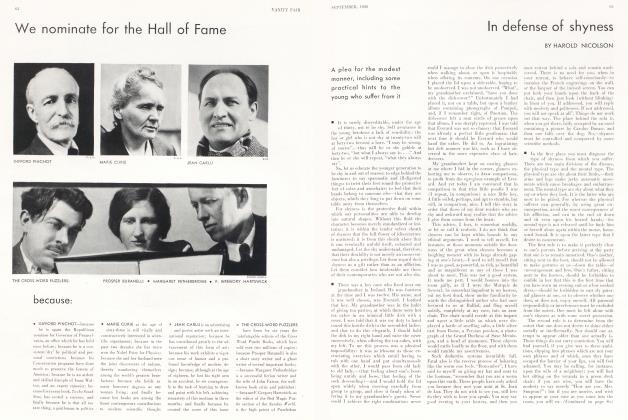

HAROLD NICOLSON

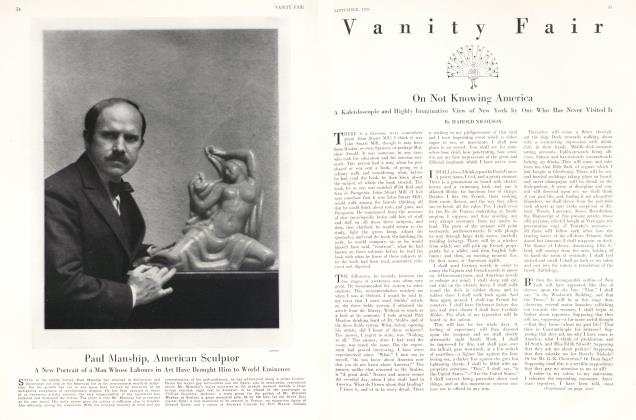

EDITOR'S NOTH: THE Honorable Harold Nicolson. author of the following article, is a prominent member of the younger English literary group; but he has also won himself a name in diplomacy. The son of Sir Arthur Nicolson, first Baron Carnock, and born in Teheran, Persia, where his father was Minister, he knew diplomatic atmosphere from the start. After leaving Oxford he entered the Foreign Office, was appointed to several European capitals, served on the British Legation to the Peace Conference, and was made Counsellor in the Diplomatic Service in 1925. In recent years he has given all his time to writing—chiefly biography and belles-lettres. He is now in this country on a joint lecture tour with his wife, the Honorable Victoria Sackville-West, the distinguished novelist.

The other day I read, for the second time, that excellent compilation by Professor Andre Siegfried, entitled America comes of age. Why the eminent Alsatian should imagine that the United States had only recently reached maturity passes my comprehension. But that is beside the point. The point is that towards the end of his book, M. Siegfried informs his compatriots that the United States and Great Britain understand each other better than do other foreign nations. I admit that the Professor may have found it necessary to disabuse his compatriots of their facile belief that the United States will tend, in every case, to take the side of France as against that of England, of La Fayette against Lord North. Were such an opinion held in the Quai d'Orsay (which it is not), an unfortunate misapprehension might arise. M. Siegfried is thus justified in warning France against a fallacy. For all that, 1 do not really believe that Great Britain and the United States understand each other better than do other foreign countries. On the contrary, I feel that we understand each other less. We in England have a clearer idea of what is going on at the back of the French mind, or even of the German mind, than we have of those recondite and rapid emotional processes which constitute the public opinion of America. You in the United States have often more understanding of the German mentality than you have of the mentality of Westminster. A month on this continent has taught me one extremely valuable lesson. It has taught me that I understand nothing about the United States whatsoever. It is for this reason that I desire, before any knowledge intervenes, to write about the British and American characters. I agree with Oscar Wilde—"ignorance is a delicate fruit: touch it, and the bloom is gone". I therefore write upon this invidious topic while the bloom is still as dust upon the damask of my ignorance.

We are taught by our internationalists of today to cultivate what they call "the will to understand". The spirit may be willing, but the flesh is weak. Clearly, what one foreign nation notices most about another foreign nation is not the similarities which render each of them types of the same genus, but those dissimilarities which sunder them the one from the other. I am not struck, for instance, by the fact that the people of the United States dress much the same as those of the once United Kingdom. I am struck by the fact that whereas American women have very tidy hair, the women of Great Britain have hair which is not tidy in the least. My attention, again, is less aroused by the curious circumstance that our two languages are, at more than one point, strikingly allied, as by the fact that when I pronounce the short "o" upon that excellent contrivance, the American telephone system, the operator, for all her comradely willingness, is unable to understand. It seems strange to me that words like "rock", "Bobby", "lock", "hot" should, in the two languages, have diverged so strikingly in intonation. The long "o" is even more difficult than its short brother. The expression "Old Gold" is not one, for instance, which any Englishman can use without causing merriment in the drug store. I have abandoned my attempts to order rolls for breakfast: "toast" is what I say now: and with toast I have to rest content.

The gulf which sunders us is, however, more than lingual. There exists between the Englishman and the American of 1933 a profound psychological rift which becomes apparent in many curious ways. There is. for instance, this business about laughing. I am one of those—and there are many of us— who like American stories. They are rather long, of course, but then your distances are so great and your club-cars so comfortable. Yet I have frequently gained the impression that the American narrator is left with the conviction that I, as a British auditor, have not seen his point. In almost every case. I have seen his point. I have smiled at the point, and if it has been a very good point I have even chuckled. But I haven't laughed. Englishmen, unless they possess exceptional teeth and an unreserved manner, very seldom laugh. And the American assumes therefrom that they have not seen his joke. This, I find, is a very current and damaging illusion. Nothing destroys amity so quickly as an unshared sense of humour. It is an illusion which I should wish to disperse.

A second, and more corrosive difference, is our divergent standards of privacy. I do not say that the dumb individualism of the Englishman is a wholly attractive quality. Yet our secretive instincts are general and profound. I do not say, conversely, that the American has no sense of privacy, since one has only to probe a slight distance to be met with a strong-box of reserve. All I say is that the proportions of what goes on in public and what goes on in private are, in England and America, very different proportions. Thus you Americans are distressed by our absence of foreground, and tend to imagine that behind our cold frontages there is little more to be discovered. And we British are disconcerted by your width of foreground and tend to imagine that behind that lavish exuberance there can be little room for depths of individuality. I believe that both of us, in so imagining, are making a mistake. We are confusing manner with temperament. The Englishman hides his private feelings behind a drop-curtain; the American hides his behind a conventional performance at the front of the stage. Yet in both cases there is much that is important which takes place behind.

Continued on page 60b

Continued from page 28

A further cause of mutual misunderstanding is, of course, this question of just being shy. When an American becomes shy, he is apt to raise his voice, to laugh loudly, and to allow the wings of the eagle to flap upon the air. When an Englishman, as so frequently happens, becomes shy, he puts on a boot-face, by which I mean a face like a boot. Neither of these manifestations is very agreeable—yet the sensitiveness which they are devised to hide is, in fact, a most attractive quality. It would be a good thing if all Americans, when they observe a boot-face in an Englishman, were to assume that he is just feeling shy. It would be a good thing if all Englishmen, when they hear an American beginning to raise his voice above the average, were to assume that he also is afflicted by this delightful ineptitude. For I have observed that when once Englishmen and Americans can conquer their instinctive shyness of each other they agree splendidly. On such occasions I feel that M. Andre Siegfried may he right. Only, as occasions, they are extremely rare.

There is also a whole area of possible misunderstanding offered by the circumstance that our habit of expression is one of under-statement, whereas the American habit is one of over-statement. This applies, not to jokes only, but to expressions of approval or distaste. An Englishman hesitates in all circumstances to employ the superlative; an American is apt to expect it.

The Englishman, moreover, has been trained to calm. The American has been trained to act as a live wire. Here in fact we touch upon something which is more than a difference of manner but is actually a difference of temperament. The Englishman inherits a long tradition of muddled optimism: the element of muddle renders him unexpectant, the element of optimism renders him silently cheerful. The American, on the other hand, has for the last three hundred years lived in an atmosphere of tense excitement: it is not surprising that, what with revolutions, frontiers, manifest destinies and bull markets, his nerves by now should be a trifle frayed. He tends therefore to be irritated by the placidity of the Englishman, whereas the latter is dismayed by the hustle of the American. They are apt, in each case, to attribute either the stolidity or the restlessness to pose. Yet in fact the one arises from a torpid liver and the other from strained nerves. If we accept these things from the outset—if we refuse to be so foolish as to attribute to affectation all mannerisms which we do not understand—then indeed we can observe in each other the very valuable qualities which these mannerisms conceal.

Yes, our dissimilarities are very apparent. There are moments even when I feel that a German visitor to this America might find himself more at home than any Englishman. He would find again that lack of individual selfconfidence, that preference for corporate action, which are so marked a feature of his own gregarious countrymen. He would welcome the frequent notice-boards and public injunctions: he would share the love of speed and size; he would appreciate the graphs, the statistics and the belief in knowledge as opposed to learning. He would feel at home with the brownstone houses, the wreaths at Christmas, the half-drawn window blinds, the disregard of personal appearance among the clerical orders, the vast Sunday newspapers, that habit of putting one's address on the hack of envelopes. the large helpings in restaurants, the way people are good at cooking hare and venison, the keys, the luggage-checking and the other precautions against theft.

There are moments when I feel the above. But, as moments, they are neither very intelligent nor lasting. In my saner moods I welcome the fact that now that the lion and the eagle are both in a pretty mess they may cease for a year or two to growl and peck. They may even—and why not? —come to respect each other for the curious qualities which the other lacks. We on our side may cease to feel indignant at a prosperity which America has herself temporarily—let us say—disavowed. We may forgive her even for having ousted us from the position of the greatest Power in the world. And on her side America may come to feel that the old lion, in that she suffers much from bed-sores, is not so militant a creature after all. The United States may even forgive us for having got there first. It is a good thing for Englishmen to remember that our forefathers had at least something to do with the settlement of this continent. It is a good thing for Americans to recollect that they also, if they desire thus to think, are inheritors of our tradition. It is unnecessary, and indeed unwise, to expect that such common acquirements should create either a maternal or a filial feeling. Yet after all they do constitute a bond not easily soluble.

It is pleasant to think of such things. Yet is it very wise? Am I not, in my present mood of gratitude towards America, allowing soft music to lull my awareness? I do not believe that amity between nations can durably be based upon pleasant feelings. It can be based only upon hard thinking. The harder I think the more different do we seem. Behind a fagade of similarity stretch whole acres of vast differences. The Englishman essentially is territorial; the American of today is urban. The Englishman is fond of nature; the American, like the ancient Roman, is afraid of her. The American likes cities; we hate them. Surely these contrasts, generalised although they be, are real contrasts? And as such, almost fundamental? By identifying our differences we may, however, isolate and emphasize our similarities. I hope so. And when it comes to the last analysis,—how likeable we both are! And how unlike!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now