Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe screen

PARE LORENTZ

MR. JOLSON—I find it unreasonably difficult to talk about music without becoming self-conscious for the reasons that: (1) a majority of music critics have refused to let the general public or each other know what they are talking about, and (2) music associations have long been so many secret societies as difficult to approach as the critics, and (3) the general public doesn't give a damn about music for music's sake anyway.

The bewildering fact to me about music criticism is that so few people in authority seem to know or care about the difference between a charming score, ably presented, and a tinny melody and an ugly production.

Movie critics as a man announced that Love Me Tonight was a good imitation of a Rene Clair picture, "with music by Rodgers and Hart", when, in the opinion of abler musicians than I pretend to be, Richard Rodgers, well educated musician, had written some very good, as well as very pleasant music for the production.

I have no quarrel with tune-deaf customers who prefer to leave their music rather than take it, but the average patron, even unwittingly, will enjoy Rodger's waltz tune in Love Me Tonight a hundred times more than he will the same composer's You Are So Beautiful, as sung by Mr. Jolson in his new picture, Hallelujah Tm a Bum, and for reasons which I shall proceed to give him as briefly as possible.

For all her bovine method of acting, Jeannette MacDonald can sing; when she appeared in that lovely exterior scene in Love Me Tonight and casually sang a charming waltz, she had every help a director and a cameraman could give her to create a proper atmosphere for the song. When Mr. Jolson sings to his nameless heroine, he is standing by a window overlooking a tenement scene and a cheap dance hall. And Mr. Jolson sings all songs as though they were entitled Mammy. No one else sings in the show except a phoney chorus of bums, and unless you like Mr. Jolson's peculiar type of singing, you won't find it a musical picture.

Neither Mr. Milestone, the director, nor Mr. Hecht and Mr. Behrman, the authors of this picture, hitherto have interested themselves in music. Mr. Jolson is too old at his musical trade to change his tricks and subordinate himself in a show. Thus, the music, the story, and the star were constantly warring with one another.

Frank Morgan, the best handy man in Hollywood, brings the picture alive in a drunken scene which, insofar as the writing goes, is the only bit in the picture creditable to its able authors. Except for this, there is no spontaneity, and but little charm in Hallelujah I'm a Bum, and what music Mr. Rodgers furnished was yanked around by its ears.

The moral, which I meant to put briefly, is that even popular music should be presented by people who genuinely like and understand music; vide, Jerome Kern, Oscar Hammerstein, Rouben Mamoulian, Ernst Lubitsch, Noel Coward, any German, and the late F. W. Murnau.

AND MRS. JOLSON—Strictly speaking. 42nd Street is not a musical picture; in fact, what with the Warners running a train to Washington to advertise it, the movie almost was turned into a gag at the expense of the new President. However, the Warner freres took no chances with the form of the picture. They chose an old story—the backstage life of a musical show—but they stuck to it, and the director told it well enough to make it entertaining.

The hackneyed formula, spawned in the first frantic days of the talkies, allows music and dancing in the picture because the plot deals with a Broadway musical comedy. Oddly enough, in 42nd Street, Warner Baxter is a rather convincing stage director, Bebe Daniels has a surprisingly good voice and a fair sense of comedy, and the dancing and song routines are introduced with some imagination. The music is of no consequence and there is another one of those toothy juveniles in the show, but the very charming Mrs. Jolson gives the entire production an authentic feeling.

She is perfectly cast, she is very attractive, and she, with the aid of a director who gives an old story vigor, makes 42nd Street a fair dramatization of the confusion and childlike excitement which attends the production of an elaborate musical show. Furthermore, to get back to my moral, the music, while of no consequence, is given a vigorous, if conventional, presentation. Had Mr. Jolson stuck to such an old story, and had Mrs. Jolson been subordinated instead of her husband in a "rhythmic dialogue" (which cracked under a one-knee delivery), they would have appeared to better advantage. As it is, Mrs. Jolson is the victor in this particular family competition.

MILL ENDS—What with receiverships, bankruptcy, abrupt decapitations and general internecine warfare, the movie industry has been producing this particular month whatever odds and ends happened to be lying around the mills. One exception is the adaptation of Topaze. The play was too frank and cynical for open translation on the screen, and instead of an outspoken farce it was turned by Harry D'Arrast and the prolific Mr. Hecht into a sentimental comedy. It was not an easy play to make into a movie because the action centers about a gentle schoolmaster, but D'Arrast made a good job of it by getting a fine performance from John Barrymore.

Pictorially, the picture has a stupid, monotonous grey quality unrelieved at any point. The manuscript becomes talky at times and many speeches—particularly those in the schoolroom before and after Topaze masters the art of politics—should have been tossed away. However, D'Arrast has a talent for comedy detail, and he keeps the picture on a comic level with some very amusing incidents. The mistress was emasculated completely out of the manuscript, and what was left was cut by the censors, so you won't find much of the original Pagnol play in the picture, but it is a better than average production.

Which is a deal more than can be said for The Crime of the Century; Face in the Sky; What! No Beer; A Lady's Profession; The Great Jasper; Men Must Fight; or Hell to Heaven. Of these mill ends, The Great Jasper was curiously pleasant because it attempted to narrate the biography of a great pre-war stallion. It is a refreshing, bucolic topic, but Richard Dix and his employers told a curiously theatrical tale as badly as they possibly could, and the production has no merit except as a historical curiosity dealing with the primeval age.

Men Must Fight is a genuinely wretched job; in fact, next to the last picture directed by Edgar Selwyn, it is one of the worst exhibits I ever have seen. As usual, Mr. Selwyn is preoccupied with entrances and exits, and for whole minutes nothing happens but some very interesting door-openings. Unfortunately, Phillips Holmes or Ruth Selwyn inevitably comes in or exits through one of the doors, which only makes it more impossible. And, as though that were not enough, someone around the studio must have read the box office figures on Cavalcade, with the result that Diana Wynyard again cries her way in and out of a war and makes some pretty bitter speeches about the whole thing. Men Must Fight could have been made into an interesting action picture. As done by Mr. Selwyn, it provides a good example for seminar study of what not to do with a movie camera.

Hell to Heaven, in all fairness, is not as meretricious as the rest of the aforementioned mill ends. It is a Dinner at Eight of horseracing. Before the various couples, whose lives are staked on the big race, get tangled up with their individual plots, the picture recreates very nicely the atmosphere of a racing hotel, and some unknowns, including Cecil Cunningham, give the picture a casual, unpretentious air. The horse-race itself is miserably fumbled by Director Kenton and all the little plots end happily in the nick of time, but it is not a disagreeable job and it has some genuine feeling in it.

BEAUTY AND THE BEASTS—The producer's statement that "a naked white giant, with his civilized sweetheart in his arms" faced it all—"it all" being a faked picture of wild beasts devouring civilized sweethearts—is indicative of what you can expect from The King of the Jungle; and the statement, "the most exotic love scenes ever filmed, performed amid some of the fiercest animal battles ever witnessed" (a statement which might have been very interesting had it been truthful) gives you a good idea of what the producers wanted you to believe you would find in Nagana; and, in fact, in all these nature in the raw epics.

Continued on page 67

Continued from page 43

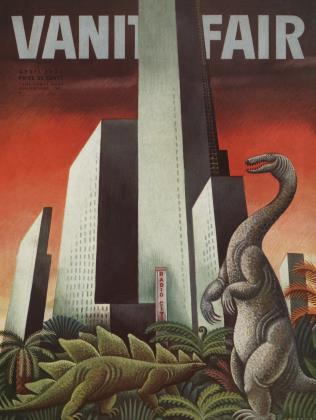

In short, instead of Lionel chasing Lillian around the Sierras, we now find the producers showing us various little Nells in the hands of lions, halfmen what-is-its, Olympic swimmers, stripped raw, Lionel Atwill done in clay, and Boris Karloff. Tarzan was amusing, and the general effect of Frankenstein was, for the most part, logical and effective. Kept in an oldfashioned fantastic mood, these jungle pictures are entertaining, but King Kong is the honey of them all. Starting with a realistic group of adventurers, led by an intrepid cameraman, who come upon some inevitable Hollywood Negroes done up in grease paint, we are led into a studio primeval forest, complete with clay dinosaurs and a gorilla known as King Kong. Immediately from this point on, the little Nell of this production takes a beating surpassed in fiction only by the great and foolish A. Gordon Pym. She is carried around in the gorilla's paw, dropped under tree trunks, attacked by assorted monsters suffering questionable but specific primeval urges, and as though being dropped thirty thousand feet into the ocean (after Kong has plucked her clothes off in a tender, lyrical scene), didn't constitute a full day's work, she is chased clear to the top of the Empire State Building where she finally and gracefully clutches her sweetheart while hanging by one hand to the spire. I would dismiss the picture as a dubious adventure tale for children if it weren't for the ridiculously bloody scenes in it, and that I do think it marks a great moment in the industry; now that they have spent half a million dollars to send a forty-foot gorilla after the girl, what can they do, what can they do?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now