Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe nullification of Senator Borah

JAY FRANKLIN

A great individualist and moralist in American politics goes down in defeat before a new day's forces

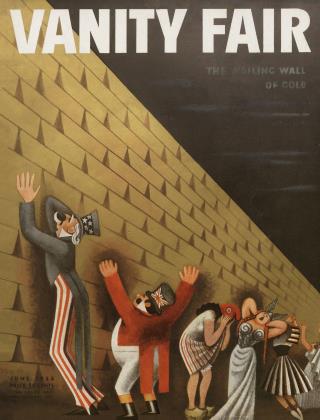

THE END OF A HERO.—In the cruel sport of American politics there are two feats which combine the ingenuity and ferocity of the Indian tortures from which so much of our political practice is derived. One game corresponds to the old trick of "running the gauntlet", in which the hraves line up in two rows and the victim runs down the aisle between. while everybody takes a crack at him with clubs, knives and tomahawks. This is most frequently employed in Presidential politics and takes the form of repealing our Presidents. We repealed Woodrow Wilson in 1920 and Herbert Hoover in 1932 with a savagery which will amaze the future historian. In these cases, the victim generally survives, broken and embittered in spirit, in a moral daze which mercifully does not permit him fully to understand the extent of his catastrophe.

For our Senators, on the other hand, and for those who are not directly amenable to the boisterous brutality of the national electorate; for men whose elections come in "off" years, or whose power is buttressed by a death-grip on State political machinery, we reserve a more subtle torture. We leave them lashed to the stake of office while we slowly tear their policies to pieces until their statesmanship is completely nullified and their reputation is destroyed. We did this to Senator Aldrich, the Republican boss of the Roosevelt-Cannon-Taft era. Today we are doing it to Senator William Edgar Borah of Idaho, the great "Tribune of the People" of the Harding-Coolidge-Hoover epoch.

One of the outstanding spectacles of political Washington is the complete nullification of Borah by the American people. Hoover, who was merely repealed, was lucky. He can hope to fight another day and can always say "1 told you so!" if things go wrong, but Borah's face must be set in self-control as his policies are consumed in the slow fire of events. Here is no Icarus-like Wilson, who soared too near the sun, but a political Prometheus. From his seat in the Senate, only death, resignation or an electoral coup de grace can release him.

His passing may be marked with sorrow. Of all the men who have come to Congress from the rotten boroughs of the West, he has best justified the iniquitous system of disproportionate representation for the great open spaces. Honest, studious and sincere, he has evaded social entanglements, scandal and corruption. He may have failed to voice the universal conscience of mankind, but he has succeeded in voicing the conscience of the Republican Party. He has spent long hours at the desk, has studied the will of the people, and has never spoken without mastery of his subject or with indifference to the aspirations of the general masses. His errors have been those not of fact but of spirit; he was word-perfect but did not always catch the tune. He was still intoning "Shall we gather at the River?" when the country was beseeching every loyal Maine man to drink. He was constantly ingeminating peace when there was no war. Yet he has carried himself with constant gravity and poise, and if his ideals of peace have outstripped the unregenerate facts, it can also be said that the world of nations has fallen short of the ideals which he persuaded it to accept. He has never been accused of cant or of blind partisanship. His failure has also been that of the era which he represents.

IDAHO—THE "ROTTEN BOROUGH"—While this is a tragic spectacle, it is by no means a Greek tragedy, for he is the victim and the beneficiary of the system by which a State with fewer inhabitants than Baltimore, alone, or Boston, Buffalo, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, New Orleans, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, San Francisco, or Washington, D. C. (not to mention New York, Philadelphia or Chicago) is permitted as great an influence over national policy as is any great State.

Politically speaking, Borah has had a cinch. His electorate is small, homogeneous and intelligent. Where Senators from Illinois, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and New York have to fight bitterly for renomination, let alone re-election, Borah gets both on a silver platter, despite his genuine indifference to public office. Due to the seniority rule which governs Senatorial committee rank, Idaho had only to send Borah to the Senate in 1907 and keep him there ever since, and in due course he became the ranking Republican member on the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee. This, in turn, meant that so long as the Republicans were in power, Borah would be chairman of that Committee, with almost untrammeled power to withhold treaties from the Senate as a whole. And with the inexorable logic of American politics, this meant that a practical veto power over the foreign policies of the United States was held by a man who represented a mountainous and semi-populated inland State, a man who had never set foot outside the United States and who was sure of reelection.

This peculiar combination of geographical isolation and political irresponsibility was too much to be resisted. Borah yielded to the besetting American temptation to be a preacher and Messiah rather than a statesman. He used his great position, combined with a studious habit of mind, a capacity for industry and a genius for political utterance, to commit his country to policies which have not stood the test of a decade. So far as foreign policy was concerned, he put the mess in Messiah; so far as concerned domestic matters, his influence has been anachronistic.

LONE WOLF OF THE NORTHWEST.—For the central defect of the Idahoan's character is his very integrity. He represents a type of statesmanship which is no longer applicable to the rapid course of contemporary events.

He is an individualist. He clings to the theory of personal rather than party representation. His convictions have never been for sale to the electorate nor mortgaged to the Republican Party. Right or wrong, he has followed his conscience and has always been ready to take his punishment from the voters. He dared oppose Boss Aldrich on the questions of the income tax and the popular election of Senators; and he dared oppose the Woman's Suffrage Amendment because it invaded State sovereignty and would lead to nullification in the South. Yet, with equal independence, he has pleaded for a Federal enforcement of prohibition in dry States after the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment and could never bring himself to admit that this amendment invaded State sovereignty. He cannot be classified as liberal, conservative, radical or reactionary.

This has led to the charge that he is a turncoat. So it was that Coolidge expressed dry surprise when told that Borah went horseback riding, as the Vermonter said he had always understood that horse and rider were supposed to travel in the same direction! But Borah has never been a turn-coat; he has been merely an individualist. Now that the world, and with it the United States, is entering an era of collectivism, the Borahs are becoming superannuated.

Much of his apparent inconsistency is due to his respect for the American Constitution. He is one of that document's most intimate friends. His opposition to the beer bill, the banking bill and the economy bill was based on constitutional grounds. He believes that political society should abide by the rules which it has adopted, or should change those rules, if necessary, by changing the men who make the rules. As an intellectual and a legal conception—and Borah is above all a lawyer who entered the Senate originally as a stepping stone in his career at the bar—this is flawless, above criticism. Yet the need for urgent action in time of crisis outstrips the forms of constitutional procedure in this, as in many other countries. The nation is actually engaged, by the implied right of popular revolution (which underlies all constitutions), in revising the charter of our Federal Government, and has little patience with constitutional lawyers. Borah is simply the same as he has always been; it is the country which has changed. Both as an individualist and as a constitutionalist, lie is being nullified by his careless countrymen.

Continued on page 57

Continued from page 16

THE MORALIST IN SESSION.—His policies were simple. They were embodied in a single conception: the moral law. Viewing humanity from the arid plateaus and extinct volcanoes of his desolate satrapy, his mind was unclouded hy contact with other nations and civilizations. Like Moses, Mohamet and other dwellers in the desert, he discerned immediately that the way to eradicate human naughtiness was to forbid it. It being assumed that American policy must reflect the moral conscience rather than the immediate mundane interests of the American people, there could be no possible incongruity in couching moral precepts in the form of statutes and treaties. Mohamet wrote the Sutras of the Koran on bits of stone, fig-leaves, and in the dust; Moses wrote the Commandments on tablets of stone; why should not Borah make like use of the legislative apparatus of the United States Government?

Competitive armaments were bad, therefore they must be prohibited. Peace was good, therefore war must be renounced. Wine was a mocker and strong drink was raging, therefore the Eighteenth Amendment must be maintained and enforced. The dwellers in the desert have never bothered to qualify their "thou-shaltnot's". Not for them the human minutiae of political aspirations, racial sentiments, social practices. Not for them the wisdom of the serpent. The voice crying in the wilderness cannot afford to be temperate in judgment on the misdeeds of others. Borah became the American Apostle of Peace, Disarmament and Prohibition by moral fiat. The period of 192030 became his decade.

It was Borah whose speeches and influence, against the will of the Harding Administration, brought about the Washington Conference of 1921-22, limiting naval armaments and halting battle-ship competition for fifteen years. It was Borah who originated the multilateral negotiation which produced the Kellogg-Briand Peace Pact of 1928, with its "pure and simple" renunciation of war as an instrument of policy (with certain curious exceptions) and its pledge to use none but peaceful methods for the settlement of international disputes. It was Borah whose cooperation secured the ratification of the London Naval Treaty of 1930. It was the Senior Senator from Idaho who was on the receiving end of Secretary Stimson's vaudeville skit of diplomatic ventriloquism, expounding the "Hoover Doctrine" by which the nations are prohibited from recognizing changes brought about by means contrary to the Kellogg Pact or the Covenant of the League of Nations. It was the Elder Statesman from Boise who bluntly told the French journalists at the time of the Laval visit in 1931 that Europe must reorganize without regard for the consequences. The spirit and voice of Borah, the Moralist, have dominated our world policy for fifteen decisive years, during which he supplied the moral background for American isolation.

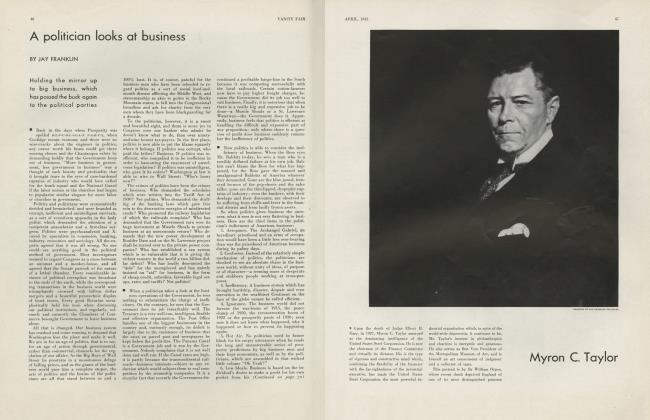

Few American politicians, therefore, have ever enjoyed such power as that which Borah exercised in his decade. The only man in our history comparable to him is Daniel Webster. The Senator dominated the Kansas City convention which nominated Hoover. Despite the "Anybody but Hoover" movement in the Farm Belt, Borah swung the farm vote to the man from Palo Alto. His moral fervor helped make the 1928 campaign a great crusade against the forces of liquor and of urban evil, as embodied in the candidacy of A1 Smith. He was responsible for calling the special session of Congress in 1929. His disarmament and peace policies were applauded in church and collegiate circles. He was "mentioned" for the Presidency every four years and in 1924, when Coolidge offered him a place on the ticket, he replied, "Which end?" He seemed to speak with the tongue of men and of angels. To the liberals, he represented the comforting thesis that the Republican Party was no exclusive appanage of corporate greed and political reaction. To the intellectuals, he represented the voice of conscience in national politics —and no still, small voice, at that! His words were loud and clear, and rolled across the waste-lands of the post-war world like the thunder of Jehovah. Presidents were at pains to conciliate him. Secretaries of State courted his cooperation. Foreign Ambassadors solicited his advice. The world press carried his speeches to the ends of the earth and his sympathy flowed like milk to any and every lost cause: the recognition of Soviet Russia, the revision of the Treaty of Versailles, the evacuation of Nicaragua by the marines, or the literal interpretation of the Volstead Act. So far as a single Senator can embody the major purposes of Divine Providence, Borah was the man.

A LEADER IS LIQUIDATED.—To-day, he is stripped of prestige and power, by the crudest of all political processes: by the force of events.

The beginning of the end appeared in September, 1931, when Japan jumped through the paper hoops of the Nine-Power Treaty, the Kellogg Pact and the League Covenant with such skill that the diplomatic world is still breathless. The conquest of Manchuria, the bombardment of Shanghai, the annexation of Jehol and the advance south of the Great Wall followed in rapid succession. Two undeclared wars raged in South America; the rise of Hitler gave Europe its first healthy war-scare since Poland's defeat of Russia in 1920: every nation seemed to be building warships and airplanes, and bigger and better manoeuvers were the order of the day.

Many thoughtless and many more thoughtful people began to ask themselves the question: "What price disarmament and peace pacts?" With that question, the mainstay of Borah's international prestige snapped in the country which had provided him with a sounding board.

Continued on page 59

Continued from page 57

The rising tide of resentment against Prohibition was equally injurious to his domestic policy. Few stopped to remember that Borah had never made a Prohibitionist speech or that his major concern had always been with the forms of the American Constitution. Popular impatience with this American addendum to the decalogue was obviously blending with the tidal-wave of resentment against economic conditions. The farmers were in complete revolt against Republican leadership. The Democrats had adopted beer and repeal planks in their platform and the Republicans themselves had wobbled into half-hearted acceptance of the alcoholic inevitable. The other leaders of Western Progressive Republicanism were going to Roosevelt. George Norris of Nebraska and Hiram Johnson of California had abandoned Hoover and the tide had set in favor of a Democratic victory.

It was then that it was evident that the boat was leaving before Borah could get aboard. He hesitated, was silent for days, and then uttered contradictory statements regarding his position in the campaign. Finally, in the closing days, he came out for Hoover. On election morning, when told that the weather was fine, the Senior Senator from Idaho remarked, "That looks good for Hoover!" and went on to explain that good weather meant that the women would turn out and vote heavily, and that of course the women were for Hoover. When the votes were counted, not even Idaho had gone Republican.

For a time, he seemed about to recapture the magic which had made him the moral mouthpiece of the American Middle West. His kindliness, integrity and independence of judgment still endeared him to the correspondents. He issued a few well-written statements from his office: pungent, unexpected, shrewdly devised commentaries on world affairs. They were ignored. The crowd had passed on, leaving him behind.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now