Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

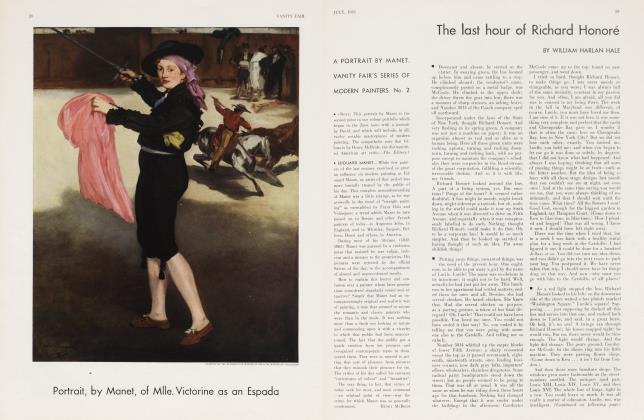

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe admiral's hat

WILLIAM C. WHITE

EDITOR'S NOTE: In far Eastern Europe, where Pilsudski scowls beneath arboreal moustaches and falls asleep at cabinet meetings, where soldiers goose-step through cobbled streets, turning their ankles, and singing "We'd die for dear old Lithuania," where "The Litts and the Latts and the Etts, the peoples one never forgets," number their navies by armed motor boats, where more political decisions are decided in Café Schwartz in Riga at five p.m. than in The High Parliament-—there is the little land of Aulania.

And these peoples of Eastern Europe know well what prestige and sovereignty and pride, particularly pride, mean to a nation.

Somewhere tonight, off the rocky shores of the little land of Aulania, is floating an admiral's hat. Tri-cornered and rimmed with heavy gold braid, it was the finest hat that could be ordered from Paris.

The little land of Aulania won its independence in 1918. By 1921 it had all those things which help to build up tbe prestige of a sovereign European nation: its own language, two million people, some war debts, an army that took three-fifths of the national income, and a State Opera which cost an over strained exchequer a million or so a year. In addition, it had Colonel Latos.

He was a handsome man in his tight-fitting grey uniform. Forty years had dealt lightly with his face, but across one cheek ran an ugly scar. Some said that he got it in Paris when a student there, in a duel fought over a remark made about Sarah Bernhardt.

"She's not a woman if she has a wooden leg," some scoundrel said. "She d be a woman even if she had two wooden legs, Latos answered. He had won the duel. Wherever ladies were concerned he always won. which made him chronically unpopular with their husbands. His general excellence in drinking, horsemanship, patriotism, and lovemaking did not add to his popularity. Worse, he was the protégé of President Martan.

"Old Jan" Martan. the hero of the Civil War of 1918. was popularly called "The Father of his Country." There was a story around town to the effect that this was the first legitimate child he had ever had.

Martan was supreme ruled by a combination of tradition and temper. The alert people of the new republic of Aulania soon discovered that the best career in a republic during a depression is in a political party. And Aulania was in chronic depression. As a result there were fifty-four parties in the Sejm, the parliament, including the Popular Socialists, the National Socialists, the Independent Socialists, the Radical Socialists, the Social Radicals, and many others, including two Communists.

Martan attended the cabinet meetings in full uniform and decorations. His eight-inch moustaches were waxed and shone like a pair of boot trees. For two or three hours (or a much shorter period when Rozanelle, the prima donna at the State Opera, was awaiting him) he would listen while his rule was cursed and challenged and criticized. He sat in silence at the head of the table firmly grasping his bushy eyebrows to keep from falling asleep. When he was tired he would do one of two things. Either lie would rise to his full height, draw his sword from its scabbard, slap it on the table and roar, "What do you petty politicians want—war or peace?" Or he would call in the police and clear away the cabinet. In any case, the meeting was over for another month.

The cabinet did not worry about Martan. He would die some day and a monument would be erected in the city square; dogs and small boys would be grateful therefor and that would be that. He had no son to succeed him. but be did have Colonel Latos. Martan bad made him minister without portfolio in his cabinet.

The old man's admiration for Latos was based on many things; Latos was a patriot, a poet, a fighter. Besides, only the handsome colonel could handle Rozanelle, Martan's best beloved. Every time she quarreled with him. Latos could always patch up the misunderstanding. Thus some of the cares of State were softened.

On an early spring day in 1921 President Martan, at the request of Colonel Latos, summoned the cabinet members for what they thought would be a usual session of insult, innuendo, and insolence. They were disturbed to find that the smiling and witty colonel was going to speak.

After tracing the history of the Aulanian people to the days of the Romans and bringing it up to date again, he asked, "Are we not as proud as any nation in the world? We have freedom, justice, an army with the most striking uniforms, and liberty. Our only flaw to date has been the twenty thousand Jews in our country who disapprove of our 'Aulania for the Aulanians' movement. In time we shall liquidate that problem.

"Yet today a most bitter blow to our national honor has been dealt us. I have just heard that the naval powers of the world are to hold a disarmament conference in Washington. Fellow Aulanians, the sovereign state of Aulania has not been invited. And why not?"

No one seemed to know. Old Marian's hold on his eyebrows hud slipped and lie was asleep.

"Because, ah, shameful! Aulania has no navy! Think now of our prestige!"

Latos paused, while inspiration mounted to high tide. "Aulania has ninety miles of sea-coast, virtually undefended, every inch of it liable to attack. We must have a navy! Self-defense demands it!"

The feeble applause awoke the old man. He misinterpreted it and ordered the cabinet to disband immediately, threatening to call the police.

"The needs of our self-defense require a navy," Latos told President Martan that evening. "Besides, think of the prestige of being a delegate to Washington or to Geneva!"

"Who do we have that could run a navy ?

Martan asked, rather disinterestedly.

"I could," the colonel said modestly. "One doesn't have to know much about technique to be an admiral. It's chiefly a matter of etiquette and good breeding and knowing how to wear clothes."

"Where would we get the ships?"

"That wouldn't cost much, at first." Latos explained that a Russian submarine had been interned at the capital since 1918. It bad never moved. "We could use that as our flag-ship until we can have a fleet of modern destroyers."

"Destroyers? Who will [jay for them?" the old man asked. His humor, changeable as a Baltic breeze, had freshened.

"Our people will be proud to support a navy," Latos ventured. "A slight increase in the agricultural tax—"

"Dog's blood! Don't talk about taxes to me," Martan roared. "A delegation of peasants came here this afternoon, protesting about the next tax on eggs. I was telling them very solemnly that economy is our motto today when in walked Rozanelle with some new furs from Paris. The delegation was not particularly impressed by that. After the peasants bad gone, she blew up about my admitting such smelly people into the apartment."

"Is everything all right between you and her now?" Latos asked, as if inviting confidences.

(Cont'd on page 53)

(Continued from page 33)

"Oh Lord, that woman!" Martan gestured in despair. "Well, you can count on a little money to patch up the submarine. But don't talk about a fleet of destroyers."

Latos first drew up a bill for Parliament, creating a navy and naming himself admiral. Then he designed a uniform for himself and sent the sketches on to Paris. The naval bill finally passed but only after complicated deals with various parties about the appointment of vice-admirals. Fourteen were finally appointed. Even at that the debate was bitter. The two Communist deputies protested loudest of all and used the opportunity to talk about the progress of Soviet Russia and of the World Revolution. The pair were dragged out and jailed for a week.

A local marine engineer was hired to put the flag-ship into commission. He reported that the engines could he operated but that the torpedo equipment was beyond repair and the diving apparatus was useless. Most important, the seams were none too strong and it would be dangerous to venture on the high seas with the

"But will it move?" Latos asked. Reassured of that, he hurried to Martan to talk further financing.

"Don't tell me anything about that damned navy," the old man harked. "Now Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Esthonia are all talking about building navies for defensive purposes. The European press says that we are showing an aggressive spirit and intimates that it would be better if we showed more interest in ceasing to persecute the Jews. Even the Americans say that we might pay a little on the war debt, instead."

"But the needs of our self-defense! Can't they understand—?"

"It's your navy. You worry about it."

"But our flag-ship may never he able to put to sea," Latos said, tearfully.

"Then run it up and down the river," Martan answered, waving Latos away. "By the way, can you swim?"

"No—"

"Good!"

Latos watched the work of overhauling the flag-ship. In time his uniform, with the tri-cornered hat, arrived, and he wore it to Café Grau every afternoon.

The first week after the flag-ship was launched was given over to a series of dinners and celebrations. Most of the three hundred members of Parliament had to he taken for a cruise. The two Communists, however, were given no such opportunity. They were in jail for having organized a demonstration to denounce the imperialistic ambitions of Aulanian capitalism.

After this Admiral Latos spent a month abroad, studying naval technique at Paris, Biarritz and Deauville.

On his return everything settled into routine. Regular manoeuvres were held on Saturdays when the Admiral, with his crew and some friends cruised up and down the river. They made an attractive picture, the grey and green of the boat and the bright uniforms of the guests as they clustered around the shining two-inch gun on the forward deck. Incidentally, the gun had never been fired and there was some doubt about the wisdom of ever using it. "My only regret is that my ship is so crowded," the admiral said. "There is no place to entertain, particularly for ladies. If we had a real destroyer—!" He had given a party on hoard during the first week but the Minister of the Interior had gotten drunk and the Navy had to stay on the river for four hours on a chilly night until he could be dislodged from the clutter of pipes under which he had crawled.

Admiral Latos now began to notice that at any mention of the navy, old Martan was liable to explode like a depth bomb. "The Poles have bought a battleship from the French so I suppose we will have to buy a second-hand one somewhere," he fumed. "Where will this race for naval supremacy end? And that's not the worst! Rozanelle insists that I should he an admiral, too, and wear that same silly sort of hat!"

The crisis came one Monday morning, with a cable from the Aulanian ambassador in London.

It was the first cable ever addressed to the Naval Department and the clerk who decoded it did not know quite what to do with it. He handed it over to the Minister of Agriculture. That gentleman took one look at it and ran to the Minister of Railroads. Together they broke into laughter and hurried to the Minister of Minorities.

Admiral Latos did not receive the cable until it had become general knowledge and the laughter, national hysteria. He took one look and paled. Then he rushed to Martan's office.

"The prestige of our country—" he began.

"If it's anything about your damned navy, keep it to yourself," Martan snarled.

"Look at this cable," Latos said simply. "A squadron of the British fleet is coming to pay a formal call on us next week. Call a cabinet meeting at once. A crisis in our history has arisen."

"How?" The old man seemed a trifle sleepy.

"The river here is too shallow and the British cannot come up to the

"What of it?"

The admiral emphasized each following word—"and we cannot put out to sea!"

The cabinet meeting that followed was marked by unprecedented unity. Unanimously, except for one vote, the members agreed that, in the interests of the prestige of Aulania, the admiral must take his flag-ship down to sea. Latos tried to compel some of the ministers to come with him hut they insisted that they knew nothing of naval affairs. Someone did suggest sending the two Communist deputies

During the next few days Admiral Latos seldom appeared in public. He found that people laughed whenever they saw him. Smiles he was accustomed to, but not laughter.

(Continued on page 59)

(Continued from page 53)

The fatal morning brought a cloudless sky. With gritted teeth, Latos clamped his tri-cornered hat on his head and walked rapidly to the pier that was the Navy Yard.

After a half hour's cranking, the engines began to revolve and the submarine slipped slowly from the dock and so slid down to sea. After two hours the Fatherland lay far behind. On the western horizon a smudge of smoke marked the coming guests. The Aulanian (lag-ship headed toward it.

The admiral paced the little deck forward, the gold braid of his uniform and his medals shining in the sun. Every inch of the boat had been polished and it gleamed. The forward gun, now uncovered, was glistening. Latos felt a slight rolling motion which had never been noticeable on the river. The idea of a sea-sick admiral was preposterous and he walked more rapidly around the deck.

The British squadron was now dimly visible across the rippling surface of the cold blue sea. Latos ordered the entire crew on deck, standing in salute, in the hope that, if some British lookout were searching the seas for the Aulanian navy, he would thus recognize it.

The British fleet came nearer, a sight to arouse the envy of anyone who coveted for his own land a position as a great naval power. Admiral Latos was thinking of the speech he could make to the Cabinet after such inspiration. It would begin, "Are we any less sovereign than Great Bri-

Suddenly the heavens seemed to collapse in chaos. The British had be gun to fire a salute.

The admiral's first reaction was to clamp his hands to his ears but he remembered the conduct becoming to an admiral. Besides, he could not move. Instinctively, he knew it was his duty to acknowledge the salute. But the forward gun had never been fired.

He stood gripped by paralyzing terror. Then he gave an order to one of his officers. The officer went below, to return in a moment. With teeth more tightly gritted, and with hat clamped down more firmly than ever, the admiral gave another order.

What happened then could best be described by onlookers on the British vessels. The Aulanian flag-ship fired a weak salute. The submarine slowly

rolled to starboard, hesitated for a moment, continued to roll, and deposited admiral, hat, two vice-admirals, and crew in the cold ocean. With its keel showing, the boat stayed motionless for a moment, then slowly sank from sight. With it vanished something of the pride of the little land of Aulania.

British boats took care of the admiral and his crew. Latos, hatless and watersoaked, was weeping.

"Our prestige," he moaned, "our prestige!" Suddenly he straightened up. "It only shows that in the interest of our self defense, we need a fleet of destroyers!"

Somewhere tonight, off the rocky shores of the little land of Aulania, is floating an admiral's hat.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now