Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWHY NOT AN AMERICAN MONARCHY?

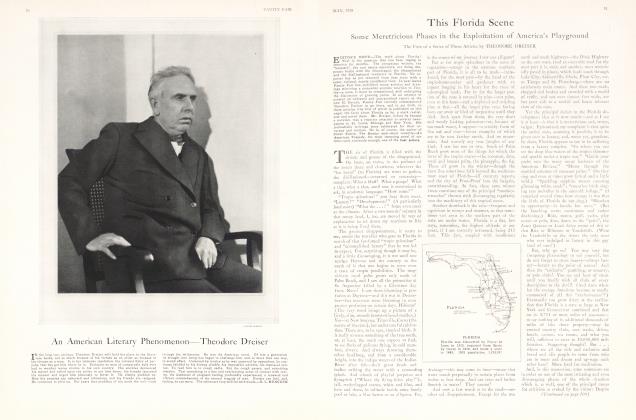

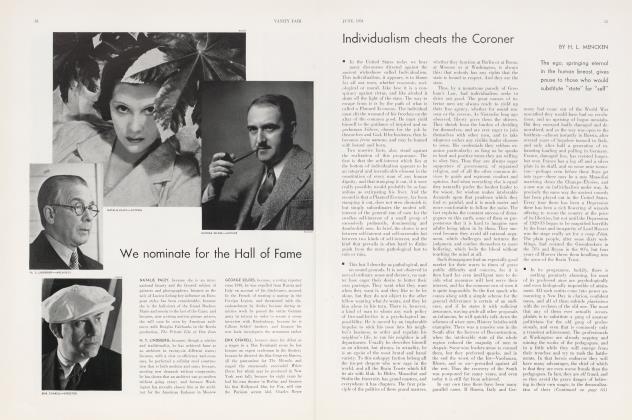

H. L. MENCKEN

If sooner or later we are to have a king, and Mr. Mencken believes we are, this is the way to go about getting one

The history of republics shows that they always tend to be transformed into monarchies—sometimes by a gradual and stealthy process, but rather more often by detonation and hemorrhage. The German republic, though it started out with friend and foe alike rooting for it, lasted only a little more than fourteen years. The French republic, the third of a series, has been going on since 1871, but who expects it to finish a century? Probably only a few romantics. It is, in fact, already down with a dozen fatal diseases, and the one question remaining at issue is whether it will be followed by a monarchy in a false-face, like those of Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Masaryk, Pilsudski, Kemal and company, or by a monarchy, open and undisguised, with a Bourbon on the throne.

This tendency is commonly put down, by the innocents who masquerade as historians, to the wicked contriving of evil men, but it is actually deeply rooted in human nature, and can't be talked away. People want to be ruled by their superiors, not by their equals or their inferiors, and human experience shows that the safest of all superiorities, taking one day with another, is that of royal birth. A king may be, and often is, somewhat stupid, but it is only by a kind of miracle that he is ever as stupid as a Harding, a Coolidge, or a Hoover. At worst, he has had some training for his job, and at best he may show a brilliant hereditary talent for it. Worst or best, he is at least a gentleman, as the word is understood in his country, and so he is above all the gimcrackeries and muckeries that mark a man who has come up from the bottom.

In the United States, as everyone knows, the children are taught in the public schools that all kings are puling paretics, and that most of them are also adulterers and murderers. Even the amiable and highly respectable King George V, I daresay, is so depicted by the more Jacobin schoolma'ams. But, after a century and a half of such teaching, the overwhelming majority of Americans, like the overwhelming majority of people elsewhere, still incline toward the monarchical idea. They think of a President, while he is in office, precisely as if he were a king, and are delighted beyond measure every time he begins acting as a king. And they think of his wife as a queen, and of his children, however dreadful, as royal princes.

THE ROYAL LINE IN AMERICAN HISTORY.—

We have had, in this country, thirtyone different Presidents, but in the list of them you will find but twenty-eight names. One was the son of a President, another was the grandson, and a third was a cousin. In other words, we have turned to the chief principle of monarchy, which is the hereditary principle, 3 times out of 31. In addition to the President's sons who have actually reached the White House, there have been at least four who have come within measurable distance of it. The first was Charles Francis Adams I, who was nominated for the vice-presidency by the Free Soil Whigs in 1848, and narrowly escaped being nominated for the presidency by the Liberal Republicans in 1872. The second was Frederick Dent Grant, who went into politics on his retirement from the Army in 1881, ' and was trotted out in Republican national conventions at least twice before he resumed his uniform in 1898. The third was Robert Lincoln, who was in the cabinets of Garfield and Arthur, and might have had the Republican nomination in 1884 if he had not refused to oppose Arthur. And the fourth was young Teddy Roosevelt, who would have been a formidable candidate in 1928 if he had beaten A1 Smith for the governorship of New York in 1924.

None of these men met the ordinary specifications for what is called presidential timber. No one would have dreamed of mentioning any of them for the presidency if they had not been the sons of Presidents. All four were given lesser but still gaudy public offices for that reason, and for that reason alone, and all turned out to be incompetent, save maybe young Teddy, who did pretty well as governor of Porto Rico.

THE ROOSEVELTS: A COMPARISON.—

Where would the present Caesar have got in politics if he had not been the elder Teddy's cousin, and a Roosevelt by name? He would have got to the lower house of the New York Legislature, and then vanished from human ken. He was made assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1913 for two reasons, neither of which had anything to do with his merits. The first was that the elder Teddy had had the same job in 1898, and had made a roaring success of it, and it seemed good party advertising to give it to another Roosevelt. The second was that it flattered Wilson to have a Roosevelt working for him.

Both the Roosevelts were lucky in the post, for wars quickly followed, and they made the first pages every day. But it would certainly be absurd to say that the naval career of Roosevelt II in the World War was as full of thrills for the plain people as that of Roosevelt I in the War with Spain. He did well enough, of course, but he never managed to seize and inflame the public imagination. Thus his nomination for the vice-presidency in 1920 had nothing to do with his record; he got it simply because he was a Roosevelt. And A1 Smith gave him the governorship of New York in 1929 for precisely the same reason. Aside from his name he was nothing, but it was expected to draw votes, and it did.

Now he is in the White House—a monument to the American fidelity to the monarchical principle. As John Smith—or even as A1 Smith—he would never have got there, but as a Roosevelt there he is. That he is anything resembling a roaring success as President I presume to doubt, but nevertheless he has some sound and useful qualities, and under different circumstances they might be of some value to the country. Unfortunately, he is horribly handicapped, as President, by the burden that lies upon all Presidents—the burden, to wit, of getting himself reelected when his term expires. He can give, perhaps, some of his day to the public business; the rest of his time and energy must be devoted to rounding up votes for 1936.

Why not liberate him, and the country with him, by making him king in name as well as in fact? Why not admit frankly that there is a Roosevelt dynasty?

HOW TO CREATE A MONARCHY.— Do I propose a revolution? Not at all. What I propose is simply the candid recognition of an indubitable fact. That recognition would not involve any violence to the present structure of the government; it might be accomplished by a simple amendment to the Constitution—and one a great deal less revolutionary than the Eighteenth or Nineteenth. Let Article II, Section 1, and the Twelfth and Twentieth Amendments (dealing with the election of the President and Congress) be struck out, and all the rest might very well stand. Congress would remain, the judicial system would remain, and the Bill of Rights would remain. So would all the other amendments save those struck out. The only difference would be that we'd have a king, and the king would be able to stand aloof from the ignoble barking and catching of party politics.

The advantages of such a change must be manifest. As things are today, an incoming President has to begin running for reelection the moment he takes the oath. He can adopt no course of action, however meritorious it may seem to him, without first figuring out how many votes it will make or lose for him. Congressmen whose jobs are in peril hang about his neck, and bellow for his aid, and he is at the center of a political machine so vast that it constitutes the nation's greatest industry. Thus he is lured inevitably into demagogy, and if he is a naturally complaisant man, as Dr. Roosevelt is, he is likely to succumb to all sorts of quacks and fanatics, and to afflict the country with a mass of costly imbecilities, all of them designed to soothe and bribe the lower orders, whose votes he needs to continue in office. Nor is he relieved during his second term, for every President who achieves a second term spends it in dreaming of a third, and when his hopes of it begin to vanish he devotes himself to grooming his successor.

A king would be above any such temptation. With his job safe for life, and secure for his heirs after him, he would be under no necessity to provide an endless ration of panem et circenses for the rabble, and so he would be free to seek the ease and security, not alone of those who yearn only to be maintained at the public trough, but also of those who work hard, save their money, and are eager to pay their own way. Kings are never Socialists, either under that name or any other. They do not have to pal with their inferiors. They are not dependent for a continuance in office on the belief of newspaper reporters that they are good scouts. The populace views them with the awe which it accords to all its rulers, however lowly, and that awe is wholly uncontaminated by any saucy thought that they need its votes.

KING FRANKLIN I.— Would

Dr. Roosevelt make a good king? I am inclined to think that he would. He is a gentleman, and he has all the natural decencies of his order. He is sincerely sorry for the underdog and yearns to help him, but he never carries his sympathy to the point of identifying himself with its object. His private associates are certainly not proletarians, and there is no reason to believe that he has any liking, save a politician's liking, for the professional saviors of the lowly. If he were free to follow his instincts he would probably turn out all the evangelists and wartremovers who now infest Washington, and put in more decorous and sensible men.

If he could forget 1936, he would also forget the mendicant one-crop farmers and their political panders. If he could give half as much thought to the dignity of his office as he has to give to hanging on to it, he would cease to clown.

Soon or late, I am convinced, we are bound to have a king. The plain people of the country bear their liberties badly, and have been trying to get rid of them for two generations past. Every invasion of them is welcomed with loud hallelujahs, and the more despotic the President, the more he is admired. The one question that remains here, as in France, is whether the restoration of monarchy will be achieved by a legitimate monarch or by some ruffianly usurper from below. Certainly Roosevelt is the most nearly legitimate candidate that we are ever likely to have, now that the Adamses begin to peter out. To be sure, he is of what the Almanac de Gotha calls a "younger line," but sometimes a younger line is clearly better than an older, and this is one of the times. In crowning him we'd be reducing young Teddy to the lowly position of a Duke of Connaught, or even of a Battenberg, and that would probably give innocent delight to countless thousands. Moreover, his immediate house has the unparalleled advantage of being legitimatist on both sides—something that has never happened in American history heretofore, and may not happen again for centuries.

That the President's family has not, so far, aroused the enthusiasm of the country is a fact that must be admitted, but it is hardly a matter of present concern. They may seize and enchant the public imagination as they grow older, just as their father did himself. If they were converted into royal princes and princesses the problem would be solved instantly, for minor royalties are always popular, and whatever they do becomes the national standard. Their present position is an extremely uncomfortable one, for a great glare of publicity bathes them, and yet they have no public function, and indeed no public position. The children of Presidents always deserve much more sympathy than they get. They are figures in a gaudy show without having any actual parts in it. Royal princes are in far better case. They are important on their own accounts.

19 SWELL YEARS.—My guess is that Dr.

Roosevelt would make an excellent king, and that he would be even more adored than he is as President. He has all of the attributes that make royalty popular —an affable, hearty manner, a wide smile that is always working, a gallantly optimistic view of life, and a tremendous capacity for enduring bores and nuisances. To most men of any sense, rushing about the country with a gang of news-reel photographers and submitting to being pawed and slobbered over by hordes of imbeciles would be intolerable, but there are men who like it, and the Rooseveltii appear to belong unanimously to that category. The present glory of the family enjoys it with charming innocence. I believe that he would enjoy it even more in an admiral's uniform, and that the plain people would enjoy him more. His normal expectation of life is about nineteen years. They would be swell years for both king and subjects.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now