Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHe is called Jafsie

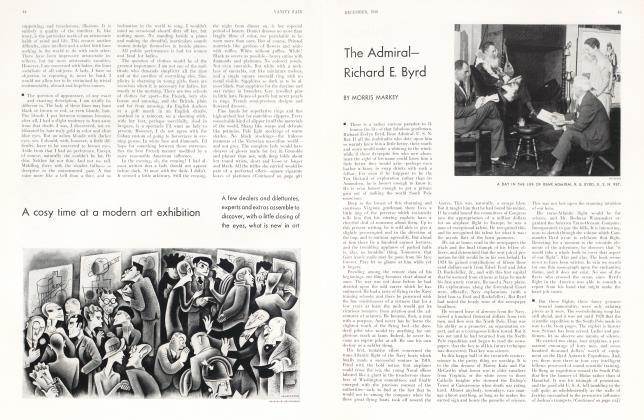

The facts about the mysterious overseer of the Lindbergh case, John F. Condon, retired school-teacher, and amateur detective

MORRIS MARKEY

Out of that whole mad gathering together of events which cost, that night in March 1932, the life of a terrified child and set a world to muttering—out of the whole flow of tenebrous drama which followed thereupon, a figure somehow more baffling than all the rest looms up.

That is the gentleman known as Jafsie.

He is not baffling because he is sinister, or because he moved in devious ways. He is baffling because, to the last, he has remained two-dimensional, seeming a little more than fabulous and a little less than real, like some character out of a gloomy Alice in Wonderland.

Suddenly, in the midst of that unnerving hue and cry, the name Jafsie was before us in the newspapers—out of nowhere, a potent and yet a wraithlike force. We could put ourselves in the places of the other figures of the drama. We knew Lindbergh, and could suffer with him. We could suffer that brief and final half-hour with the child. We could even get into the shoes of the murderer, skulking with him, thinking and hiding and plotting. But we could not realize Jafsie. We could not grasp him, nor feel with him as he stood talking in the darkness to the fugitive, as he threw fifty thousand dollars over a cemetery wall into the fugitive's hands.

It was because of this general difficulty in understanding his vague figure that the police, over and over again during those days following the discovery of the child's body, when it was known that the giving out of the money had been useless, were forced to say with great emphasis that Jafsie was not a suspect, that Jafsie was absolved of all connection with the crime, that Jafsie had been deluded along with Lindbergh and all his advisers.

There were enough strange characters, Heaven knows, in that other great American crime, the Hall-Mills case. But we could, in some fashion, understand the pig-woman. We could grasp the meaning of poor Willie Stevens, and Jimmie Mills and the dark forbidding presence of Mrs. Hall. It was not so with Jafsie—the pedagogic ancient who went around with a bodyguard and suddenly became the go-between.

I am going to do the best I can, now, to tell you something about him. You will find the facts prosaic enough. But whether they will completely dispel the atmosphere of mystery about Jafsie, I am not sure. Even after I have found out a little about him, he is certainly a great deal less than an open book to me.

His name is John F. Condon, and his nickname comes from phonetic runningtogether of his three initials. He is seventy-two years old, and had spent all his life as a school-teacher—not a distinguished educator, but a school-teacher, finally rising to be principal of a grade school. He held that job for thirty years until he was retired.

He had lived all his life in the Bronx, gathered a little nest of savings, and at the time of the kidnaping he was virtually a solitary, living in a small house which he owned.

In appearance, he is a strange contrast between the formidable and the tame. For while he is an immense man, over six feet and weighing a solid 250 pounds—a devotee to athletics, enthusiastic amateur boxer and coach of all his school teams— his face is quiet and hospitable. He sets out to be a gentleman of the old school in his manner: his manners are courteous and therefore archaic, his gestures are the gestures of a stage gentleman. Yet he so ignores his dress and appearance that he always seems dishevelled. His four-in-hand tie is a twisted knot which does not hide his collar button. His suits are good quality, completely uncared for.

Al Reich was not his bodyguard, though the newspapers called him that. Reich was a prize-fighter of sorts whom the old gentleman took up and made a friend of, simply because he felt so keenly about the worthiness of physical fitness. Once, during the ransom negotiations (which Jafsie dramatized to the fullest possible extent) he told newspaper men that Reich was his bodyguard. I have no doubt that he believed it thoroughly at the time, believed in the necessity for having a bodyguard during those excited, confused days.

When the Lindbergh baby was kidnaped, Jafsie, living in the Bronx, was a rather quiet and altogether harmless busybody. I do not say that to discredit him. Any old gent of his years, with income secured and nothing much to do is likely to stretch an eager hand toward the management of other people's affairs. He was in on all the Borough doings. He was a Bronxite first and a New Yorker afterwards. He loved children. He loved virtually everybody. He was a kindly old fuss-budget, ready and willing to talk about anything under the sun.

It was this final attribute which chanced to win for him his great celebrity.

There is a local newspaper in Jafsie's Borough called the Bronx Home News. Like local newspapers everywhere, it seeks the local angle on any story that happens to break. And the editor of the Home News had learned, from pleasant experience, that when a local angle was utterly lacking Jafsie could be relied upon to furnish it— with a statement, a theory, a touch of advice. In short, he was a "newspaper spokesman", ready to give his views on all subjects.

So, on March 8, one week after the kidnaping, when Bronx angles on the tremendous story simply did not exist, the editor of the paper called on Jafsie. "Give us fifty words," he said, "about the Lindbergh case."

Jafsie came through. He announced that he would give his life-savings of $1,000 for any information leading to the whereabouts of the child. He called, in trembling words, upon the kidnaper to get in touch with him.

The paper, on the stands at about 4 o'clock the next afternoon, carried this Bronx angle in a front-page box. Twenty hours later Jafsie received a letter from the kidnaper saying that the latter was willing to negotiate.

You see the incredible chance of it, the whimsical prank of destiny. Jafsie had done only that which he had done a score of times before—given the paper something to print. And suddenly he was thrown into the whirlpool.

You know the rest.

Jafsie answered the kidnaper by means of advertisements in the personal columns of the newspapers. He got letters from the kidnaper, both by mail and by the hand of an innocent taxi-driver. He talked to the Lindbergh lawyers and to the police, and all of them were convinced, by the strange symbols on the notes he got, that he was in touch with the real villain. He got from the kidnaper the baby's sleeping garment as an evidence of good faith, and he gave in exchange a handful of safety pins from the crib as an evidence of good faith, talking to the kidnaper for an hour in the darkness and coming back to say that he was a "Scandinavian who says his name is John". Then more advertisements in the newspaper—"Money is ready. Jafsie" —and, "I accept. Money is ready".

So finally, one fraught night, he was sitting in a car with Charles Lindbergh, seventy thousand dollars in a packet in his hand (for the criminal had increased the amount of the ransom by now) driving as the kidnaper had directed him to drive.

(Continued on page 66)

(Continued from page 31)

He was standing (this night of April 2, 1932) on one side of the high wall at St. Raymond's Cemetery, bargaining with the kidnaper on the other side and finally making him agree to accept fifty thousand dollars instead of seventy thousand. He tossed the money over the wall, and came back to Lindbergh, and they drove back to Jafsie's house to await instructions from the kidnaper—instructions as to how they might find the child.

On May 12, they found the body of the baby.

So Jafsie had come into the grievous business from nowhere. He had been the instrument whereby the murderer won reward for his crime. And this much was irony.

But Jafsie did not leave the case. All his life he had been intensely interested in puzzles, riddles and detective stories, and now this interest became not a hobby but a passionate devotion. He became, in short, a detective—more active perhaps than any other detective on the case. He went everywhere, assuming countless disguises. For a while he took the role of waterfront tough, so that he could listen to the talk in low dives. Again, he went about as a doddering and stupid ancient. At least once, he dressed up as a woman.

During the next two years he travelled thousands of miles and spent $10,000 of his own money (his original statement about his life-savings of $1,000 had been drawn a little fine) looking at suspects, listening to their voices, trying to identify that "John" to whom he had talked twice in the darkness— an hour the first time, twenty minutes the second. Jafsie had found a new career. He had found it by chance, and still it crowded his fading life.

Then, one day, they arrested Richard Bruno Hauptmann. They took Jafsie to him, even before Col. Lindbergh had seen him, and the two spent an hour alone. Jafsie came out of that first interview, sad and confused, but filled with the necessity for honor.

"I cannot positively identify him," he said. "I cannot identify him at all."

Was this another irony? Or merely something to throw us back again upon the queer unreality of this old man, making him seem more than ever something out of a half-dream?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now