Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Theatre

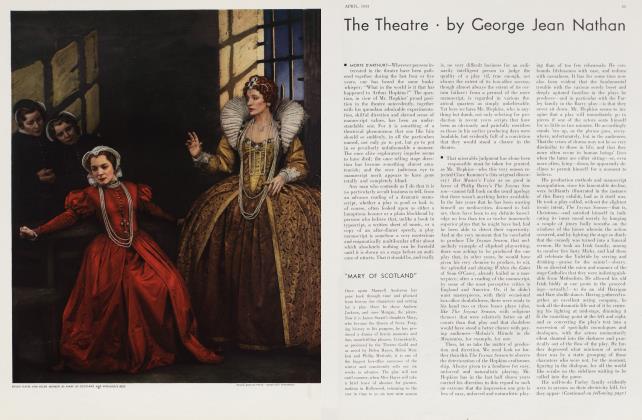

George Jean Nathan

■ GARBOING THE STAGE.— The current striking advantages in not being an actress are clearly perceptible in the case of the much discussed Miss Katharine Hepburn. It has been a long time since any young woman with histrionic competence ten times greater has achieved one-tenth of her popular success. Indeed, playing lately in The Lake with such old and richly experienced hands at the acting business as Miss Blanche Bates, Miss Frances Starr, Mr. Colin Clive and a scrupulously selected company, she not only submerged them so far as audiences' interest was concerned, but so impressed her ordinarily skeptical and very critical producer, Mr. Jed Harris, that he starred her above the entire troupe. This troupe acted rings around her, but—save for a due brief recording of the fact by a few of the reviewers the morning after the premiere—it did not matter a hoot. So far as the customers went, it was Hepburn Hepburn siss boom ah, and that was all there was to it.

At this juncture, one or possibly even so many as two readers who still take a vague interest in genuine acting may venture to ask the reason. The reason, it seems to me, is that—aside from such one or two readers and their audience equivalents, together with perhaps one out of every three theatrical critics—no one any longer takes much interest (however loudly they may contend they do) in acting as an art and that even those who do take such an interest seldom recognize real acting when they see it. (I refer you, if you are doubtful, to the common ecstatic appraisals of secondraters and the bland condescension to certain first-raters on the part of the latter group.) Ours, as I hazarded in these pages several years ago, is no longer an actors' theatre but a dramatists'. Every now and again, to be sure, some actor comes along and, like Mr. Henry Hull, startles and overcomes lethargic criticism in his department by covering his still moderately youthful face with a crepe whisker, walking with a George M. Cohan slouch, injecting into his vocal delivery a Hamtree Harrington squeak, and so presenting a very excellent approximation to a portrait of a Georgia cracker, and every now and again some actress appears and, like Miss Helen Hayes, accomplishes a similar end by giving a highly competent performance of Rose Trelawney in the role of Mary Stuart, but in the general run of things the day of audiences' and even critics' intelligent concern and enthusiasm over the actor's art seems to be, at least for the hour, over. .

If you do not believe it, consider the situation on the local stage as I write. Who —apart from the Mr. Hull and the Miss Hayes alluded to, and, of course and properly, Mr. George M. Cohan—are the players attracting the greatest notice from audiences and, either immediately or reflectively, the critics? I give you the list. Tonio Selwart, in The Pursuit of Happiness, a pretty young fellow from Central Europe and an Aryan paraphrase of Francis Lederer, who substitutes a very ingratiating manner and a pleasantly strange accent for any discernible real acting ability. Polly Walters, in She Loves Me Not, a cutie who looks even cutier with half of her clothes off. Elisha Cook, Jr., in Ah, Wilderness!, a satisfactory juvenile, but surely nothing suggestively much, at the moment, beyond that. Bruce Macfarlane, in Sailor, Beware!, a good-looking very bad actor. Basil Sydney, in The Dark Tower, a player of considerable talent (recall his Hamlet) who has been praised no end on this occasion simply because, at one stage in the proceedings, he disguises himself with a make-up that deceives perhaps one-half of the audience. Mr. Sydney, who is an actor with some critical sense, is doubtless the first to chuckle over these tributes to his art which should properly be bestowed upon a childishly easy manipulation of a blond wig, some pinkish grease-paint and a Joe Weber belly mattress. Roland Young, in Her Master s Voice, who, giving a good comedy performance, is nevertheless giving exactly the same comedy performance, without the slightest variation, that he has been giving for years both on the stage and in the movies.

J. Edward Bromberg, in Men In White, because he is the mouthpiece of the author's more noble sentiments, speaks them in much the same throaty Wilson Barrett tones that have led the same persons to regard Lionel Barrymore as a sterling artist, and remains immobile, a la William Gillette, while the action and loud talk swirl tumultuously around him. Mary Morris, in Double Door, who, in the rôle of the grasping and venomous spinster villainess, speaks and comports herself from the first to the last curtain like a zombie out of the old Drury Lane melodramas. And Laurence Olivier, in The Green Bay Tree, who looks exactly like two or three hundred head of movie Colmans, Asthers, Lowes, Rolands, Baxters, Boles, and acts exactly like them, thus affecting the ladies in the same way and spot.

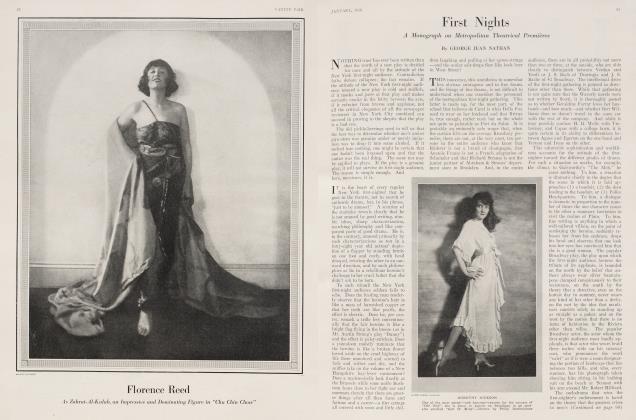

Who, in addition, have evoked the audience and critical applause in the earlier months of the season? I give you that list as well. Miss Jean Arthur, a disturbingly attractive young woman, in The Curtain Rises, who may hardly yet be said to be anything more than a disturbingly attractive young woman who may some day possibly be an actress. James Bell, a competent actor, in Thunder On The Left, who, absurdly cast in an absurd role, was admired for not being able to do anything in an acting way with it. Miss Florence Reed, in Thoroughbred, for making up as a hobbling old woman, squatting on a sofa, and pointing her every acidulous remark by thwacking each passing member of the company across his posterior with her walking stick. A little girl named Jean Rouverol, in Growing Pains, for acting like a little girl named Jean Rouverol. Miss Mady Christians, in Divine Drudge, an actress of experience and skill, because— while she had no slightest opportunity to employ her experience and skill—she nevertheless looked beautiful. And, finally, though this is perhaps a not altogether fair example, Miss Miriam Hopkins, in Jezebel, who—while it was generally agreed that her performance was negligible —nevertheless aroused such enthusiasm with her magnificent frocks and golden hair that even our good old friend, Groucho Hammond, after his third—or was it his fifth—jeroboam, whooped her up as a combination of Rachel, Rejane, Bernhardt and Duse.

And now the Mlle. Hepburn, a star after just two brief previous appearances on the stage: one as a routine ingenue in Art and Mrs. Bottle, the second as a half-nude flapper in The Warrior's Husband! Miss Hepburn, it is quickly to be observed, has many of the qualities that may one day make her an actress of quality and position; she has the looks, the fine body, the sharp intelligence, the audience personal force, the determination, and a readily detectable integrity. But that day, despite the fact that the moving picture public already hysterically regards her as such an actress, is—for the theatre and drama—still far from being at hand.

The Lake, in which our heroine has been appearing, is in the original a dubious chowder of early English drawing-room comedy and quasi-Chekhovian symbolism by the late Dorothy Massingham and Murray MacDonald. Stupidly revised for American consumption, it became doubly muddled and inert. Nor did the customarily dexterous Mr. Harris do anything with his direction to help matters.

(Continued on following page)

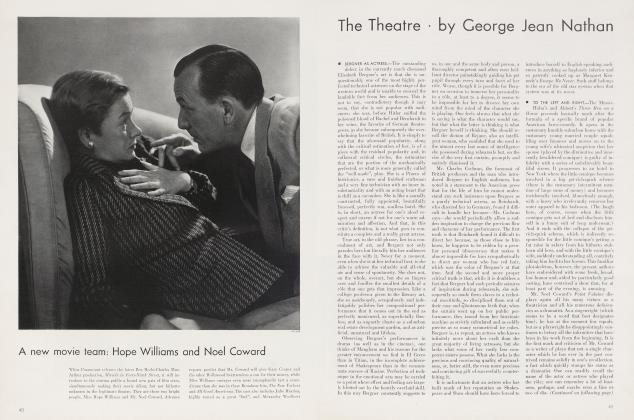

■ L'AMOUR ET—MON DIEU.—Those critical spirits in our midst who contend that, not Eugene O'Neill, but everyone else from Mr. Robert Sherwood to the Hattons is the first dramatist of the American theatre will find great comfort in O'Neill's most recent play, Days Without End, which is not only, along with Welded and Dynamo, one of the poorest things he has written but which, in addition, is one of the dullest that has come to the more ambitious stage in some time. Further comfort, if it he needed, will be afforded them in the undeniable fact that it is one of the most unbroiled plays that has been composed upon its general theme. And to make matters worse for those of us who believe in O'Neill's very considerable talent and better for those w'ho don't, the fellow actually considers it the best play he has ever written!

From beginning to end, save for two brief flashes, this Days Without End is a tournament in collegiate theorizing artlessly bamboozled into a superficial aspect of grave experimental drama by a recourse to masks and to the technical device—favorite of Viennese and Hungarian playwrights like Schnitzler and Molnar in the years before the War—of coordinating the narration of a hypothetical fiction story with the ac tual lives of the immediate characters.

It comes to the old tale: when O'Neill goes in for pure emotion, he is a sound and enormously effective dramatist; but when he ventures into theorizing and philosophizing, he is—to be very gallant about it—far from palatable. In the present play, he had a play of pure emotion, exalted emotion even. But every time it pops up its head he gives it a mortal clout with a pseudo-ratiocinative bladder. The result is chaos—and tedium.

Days Without End, a reconstruction of the Faust idea (with Faust and Mephistopheles imagined as one) and seeking its resolution under the Cross of the Catholic Christ, cries piteously for a poetry that is nowhere in it. Its lines are not only banal and humdrum, but—worse—at certain moments when only the high and thrilling beauty of the written English word might bring it a second's exaltation, the author descends to such gross argot as "Forgive me for butting in" and the like. The net final impression is of a crude religious tract liberally sprinkled with a lot of dated Henry Arthur Jones sexjn an effort to give it a feel of theatrical life. O'Neill subtitles his play, "a modern miracle play". It is not modern, as he himself should realize, since he originally wrote it with the scene set back something like fifty years. And, if he knows the miracle plays, which he most assuredly does, he certainly realizes that this forced, tortured and hocus-pocused slice of greasepaint drama is anything but a miracle play in the sense of such a play's cool simplicity, and innocence, and moving dignity.

In this work of his, O'Neill—as in other of his unsuccessful theorizing matches— again suggests a bulldog ferociously battling a Haldeman-Julius Little Blue Book. It shows nothing of the cold, hard, calm critical gift which, paradoxically enough, he exercises upon his unadulterated emotional plays. In place of that cold selfcriticism, which has provided our American stage with some of its finest plays, we find here an intoxication with what may be called logicalized emotionalism, which turns out to be neither logic nor emotion but only a bogus Siamese twin. The passion that should have gone into the play's emotional and spiritual fabric is spent upon what the author evidently cherishes as a sacrosanct amorous ethic, an ethic that seems more and more dubious as his passion continues indignantly to inflame and apotheosize it. Aiming at a climactic exaltation of the spirit, he succeeds infinitely less in accomplishing his purpose than whoever the play-carpenter was who years ago made the honky-tonk version of Faust for Lewis Morrison and brought his final curtain down • on Mephistopheles' bafflement and frustration by having the tin covering fall loudly off a cross atop a church and having the cross suddenly illuminated, like an old Shubert chorus, with a lot of very dazzling and embarrassingly pink electric bulbs.

The Theatre Guild gave the play, in most particulars, a careful production, especial credit being due to Mr. Lee Simonson for some imaginative settings and spme excellent lighting. Earle Larimore acquitted himself nicely in the central role, and Stanley Ridges, as his masked alter ego, did all one supposes any actor could do, his director permitting. Robert Loraine managed the small priest role well enough. But whoever cast the flint-hard and resolute Miss Selena Royle for the delicate, highly sensitive wife owes an explanation to a large portion of head-scratching audiences.

■ FOOTNOTES.—Come of Age, by Clemence Dane and Richard Addinsell, was unbelievable doggerel (recited to a feeble musical accompaniment) treating of Thomas Chatterton's fancied presence in the modern scene. The script sounded as if it had been written by Eddie Guest. The music often sounded like Jerome Kern's lawyer arguing with Irving Berlin's.

Wednesday's Child, by Leopold Atlas, was a nicely imagined but very amateurishly written and poorly produced study of a child's reaction to his parents' amorous excursions, separation and divorce, here and there suggestive of the late Avery Hopwood's This Woman and This Man and the familiar French play, Poil de Carotte. In more competent hands it might have stood some chance.

False Dreams, Farewell, by Hugh Stange, was a crudely fashioned stage echo of those various movies which have dealt with the interlocked lives of passengers on a doomed trans-Atlantic liner.

Mahogany Hall, by Charles Robinson, was a college boy's sentimental reflections on an old sporting house, with the Madame presented as a great lover of Beethoven and Chopin, and the author crying sophomorically into his reminiscent beer.

(Additional reviews by Mr. Nathan will be found on page 60)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now