Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

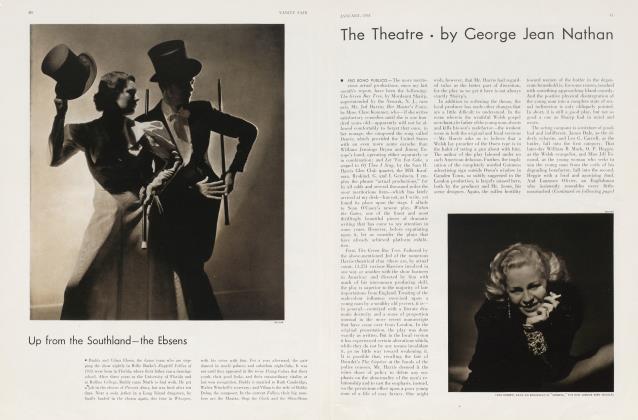

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Theatre

George Jean Nathan

■ STEIN ON THE TABLE.—For the purposes of a final dissection and a good critical song ringing clear, let us put Gertrude Stein on the table and determine, now that her self-admitted chef d'oeuvre, Four Saints in Three Acts, has been delivered to us, just what is or isn't inside her. It is Miss Stein's stout contention that the meaning and sense of words placed together is of no importance; that it is only their sound and rhythm that count. This, in certain specific phases of artistic enterprise, may—for all one's initial impulse to impolite titter—be not entirely so silly as it sounds. Beautiful music often is meaningless (in the same sense of the word) and yet finds its effect and importance in sound and rhythm. Poetry, also, often finds its true reason and being in a complete lack of intelligence and in the vapors of lovely sound and lulling rhythms. Painting, too, need not have "meaning", nor "sense", but may project its power alone by form (which is rhythm) and by color (which is the equivalent of sound). Even drama itself may have little meaning and sense, yet may evoke a curious meaning - within - absence - of - meaning (regards to Dreiser) none the less; for example, Strindberg's Spook Sonata or—to go to extremes in even absurdity—something like John Howard Lawson's The International.

Up to this point, there conceivably maybe something in Miss Stein's literary bolshevism. But now let us see how she combines theory with practise. In demonstration and proof of her conviction that the meaning and sense of words are of infinitely less significance than their sound and rhythm she presents to us, in the chef d'oeuvre mentioned, such verbal matrimony as the following (I mercifully quote but three samples) :

1. "To know to know to love her so. Four saints prepare for saints. It makes it well fish. Four saints it makes it well fish."

2. "Might have as would be as would be as within within nearly as out. It is very close close and closed. Closed closed to let letting closed close close close chose in justice in join in joining. This is where to he at at water at snow snow show show one one sun and sun snow show and no water no water unless unless why unless. Why unless why unless they were loaning it here loaning intentionally. Believe two three. What could he sad beside beside very attentively intentionally and bright."

3. "The difference between saints forget-me-nots and mountains have to have to have to at a time."

Repressing a horse-laugh and hitching up our ear-muffs, let us meditate this archdelicatessen. That Miss Stein is absolutely correct in announcing that it has not either meaning or sense, I hope no one will be so discourteous as to dispute. But if Miss Stein argues that, on the other hand and to its greater virtue, it has rhythm and beautiful sound, I fear that I, for one, shall have to constitute myself a cad and a bounder and inform her that she is fish and it does not make it well fish either. In point of fact, anyone with half an ear to rhythm and sound (whether in song, in reading, or in recitation) can tell her that any such arrangement of words—to pick at random—as "beside beside very attentively intentionally and bright" is not only lacking in rhythm and pleasant sound hut that, in addition, it is painfully cacophonous. It is perfectly true that words shrewdly strung together may he meaningless and may still sound better than words strung together with some meaning— take Eddie Guest's poetry, for instance—but one fears that Miss Stein has not mastered (he trick which she so enthusiastically sponsors and advocates. I am no Gertrude Stein, hut I venture constructively to offer her a laboratory specimen of what she is driving at and fails to achieve. The example: "Sell a cellar, door a cellar, sell a cellar cellar-door, door adore, adore a door, selling cellar, door a cellar, cellar cellar-door.'' There is damned little meaning and less sense in such a sentence, but there is, unless my tonal balance is askew, twice more rhythm and twice more lovely sound in it than in anything, equally idiotic, that Gertrude ever confected.

One more point and we conclude our performance. Granting for the moment Miss Stein her premise that the rhythm and sound of words are more important than their sense and meaning, may we ask how she feels about a possibly perfect combination of the two? Does she, or does she not, believe that beautiful rhythm and beautiful sound combined with sense and meaning may constitute something finer than mere rhythm and sound wedded to meaninglessness and lack of sense? While she is pardonably hesitating to make up her mind, let us ask her to consider such things, for example, as the hauntingly beautiful Marlowe speech in Conrad's Youth, or Caesar's parting from Cleopatra in the Shaw play, or Dubedat's from his wife in the same writer's The Doctor's Dilemma, or Brasshound's from Cicely in the same writer's Captain BrassbountTs Conversion, or Candida's from the poet Eugene in the same writer's Candida, or Galsworthy's "To say goodbye! To her and Youth and Passion! To the only salve for the aching that Spring and Beauty bring the aching for the wild, the passionate, the new, that never quite dies in a man's heart. Ah, well, sooner or later all men had to say goodbye to that. All men—all men! . . . He crouched down before the hearth. There was no warmth in the fast-blackening ember, but it still glowed like a darkred flower. And while it lived he crouched there, as though it were that to which he was saying goodbye. And on the door he heard the girl's ghostly knocking. And beside him— a ghost among the ghostly presences-—she stood. Slowly the glow blackened, till the last spark had died out." Or a hundred passages from Shakespeare, or a score from George Moore. Or some of the prose of Max Beerhohm, or Cabell's Jurgen chapter, "The Dorothy Who Did Not Understand", or Maurya?s magnificent wail to the sea in the Synge play, or some such line from Sean O'Casey's Within, the Cates as "To sing our song with the song that is sung by a thousand stars of the evening!" Or Dansany's little two hundred word fable The Assignation from its beginning "Fame singing in the highways, and trifling as she sang, with sordid adventurers, passed the poet by" to her final whisper "1 will meet you in the graveyard at the back of the Workhouse in a hundred years.

Come on, Gertie, let's hear what you have to say.

■ A SUPERIOR PLAY.—To the interest and enterprise of an actor—and to one who has spent much of his time in musical shows at that—we were indebted for the American production of the finest play of the local season: the Richard of Bordeaux of the Scotswoman who writes under the name of Gordon Daviot. Though it had been running for more than a year in London and though all the Americans who had seen it there were as loud in their admiration of it as the English themselves, none of the local managers and producers, apparently, were sufficiently interested to consider a New York production. And it is extremely unlikely that, had not Mr. King gone about the business, it would ever have found such a production.

THE SEASON'S BEST PLAYS

Richard of Bordeaux Ah, Wilderness!

Tobacco Road Her Master's Voice Mary of Scotland The Green Bay Tree Dodsworth Yellow Jack

THE SEASON'S BEST REVUE

As Thousands Cheer

THE SEASON'S BOOBYS

It Pays to Sin When in Rome The Gods We Make Move On, Sister Whatever Possessed Her Theodora, the Queen Love and Babies The Sellout

(Continued on following page)

Which brings up the point, that many of the more interesting plays and productions would have been denied the American stage had it not been for the endeavor and courage of actors.

The great rank and file of managers and producers persistently ignored these plays and hesitated to make these productions. It was the actor Faversham who gave Stephen Phillips, with Herod, his best bearing, as it was the actor Arnold Daly who introduced and fought for a hearing of George Bernard Shaw. It was the actor Miller who brought William Vaughn Moody to the stage, and the actor Mansfield who brought Cyrano. It was the actress Mrs. Fiske who encouraged the dawning better - grade American play three decades ago, and it was the actress Margaret Anglin who, in the midst of the prevailing managerial mush, deepened the stage with the Greek classics. It was the actress Grace George who brought over, and herself translated, some of the better modern French comedies; it was the actress Le Gallienne who gave a hearing to Jean Jacques Bernard and Susan Glaspell, both unpopular playwrights; and it was an ex-Follies girl, Peggy Fears, who last year produced the best musical comedy that the local stage had had in many years. It was the actress Katharine Cornell who, though true enough she could see nothing in O'Neill's Strange Interlude, when it was submitted to her, nevertheless produced Besier's The Barretts of Won pole Street after exactly twenty-seven managers and producers (by Richard J. Madden's statistical records) bad peremptorily rejected it. It was the actor Henry Hull whose interest alone made possible the present season's production of the meritorious Tobacco Road. The list might be extended indefinitely. And it has been and is the same, to an even greater degree, in England and France, from Lillah McCarthy up and down in the former to Gémier down and up in the latter.

Richard of Bordeaux was, to this way of thinking, the most successful of all the modern attempts at the romantic historical drama. The chronicle of the delicately constituted son of the Black Prince, it is written in a superbly direct, simple, enormously dramatic and beautifully managed prose; its dramaturgy is manoeuvred with an admirable economy; and the mind behind it is the mind, unmistakably, of a sensitive and sure dramatic artist. The modern critical snobbery withheld from it, I believe, its rightly full ration of praise.

■ DRAMATIZATIONS.—There is an old critical legend to the effect that dramatizations of novels are seldom satisfactory and are usually destined to failure.

It is true that certain dramatizations are as little satisfactory to the critics as to the general public; and it is equally true that the stage version of a novel must necessarily omit certain elements valuable to the novel form that are invaluable to the dramatic, and so disappoint the playgoer who remains, in his theatre seat, refractorily a reader. But a careful survey of the American theatre reveals the fact that not only have dramatizations of novels been as close to the taste of its public as a like proportion of original plays, but that, in addition, they have figured among the most uncommonly prosperous of all theatrical ventures. And what is more, a considerable number of them have been acceptable to the critics.

It would be possible to take up several pages in an incontrovertible statistical proof, but I merely suggest the general outline of the proof by recalling dramatizations of novels—all successful and many of them endorsed by the critics of their day— ranging from East Lynne to Uncle Tom's Cabin. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde to Salomy Jane, Little Lord Fauntleroy to Becky Sharp. Camille to The Honor of the Family, Sapho to Sweet Kitty Bellairs, The Corsican Brothers to When Knighthood Was In Flower, Ben Hur to Trilby, and Monte Cristo to Rip Van Winkle. Many of these, it will be recognized, made great fortunes. What, too, of The Prisoner of Zenda, of The Christian, of Raffles, of Under Two Flags, of The Three Musketeers, of Sherlock Holmes, of The Little Minister, of The Great Adventure, of Monsieur Beaucaire, of Seventeen, and of Treasure Island? And what, to come a bit closer to the present, of The Bat, The Masquerader, The Green Hat, The Age of Innocence, Payment Deferred, Alice in Wonderland, Tobacco Road, and Dodsworth? For every failure like Thunder on the Left, or Elmer Gantry (the fault not of the critical theory of dramatization but of the dramatizer), you will find a success. And probably two.

Sidney Howard's dramatization of Sinclair Lewis' Dodsworth provides an illuminating example of what a skilful stage craftsman can do with a novel, both in behalf of dramatic critics and the paying public. Out of the book he has fashioned, and with its author's delighted concurrence in and complete approval of the result, a play that translates to the stage the characters and essence of the original so adroitly that the play actually has the air of having been created out of its own womb.

(Additional reviews by Mr. Nathan will be found on page 76)

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now