Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRoom-service

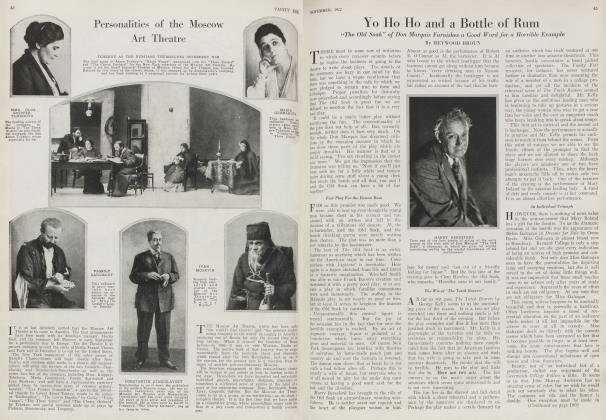

HEYWOOD BROUN

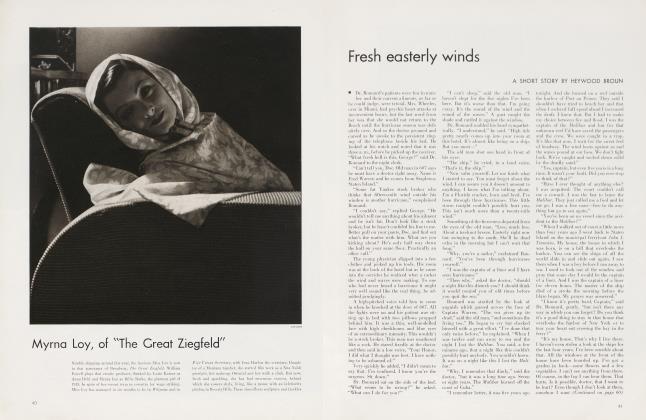

"Just an old offender back to the scene of his crimes," said Fred Dore as he slipped into a vacant chair at the round table in front of Blake s bar.

Tom Keating greeted him with enthusiasm. Then he turned to the young fellow with whom he was drinking. "This is Fred Dore who was our city editor back in 1910 and before that one of the best reporters New York ever knew. Fred, meet young Ralph Stanley, who's on the Express. Sit down. We were just discussing the freedom of the press; the business office getting bigger and the editors getting smaller."

"Well, said Dore, "in my day, papers were what Lincoln said a country couldn t be—half slave and half free. We were honest enough around the edges but still a big department store was a big department store and if a story broke in a hotel we always gave 'em the break of not using the room number."

" The room number? ' said young Stanley in a puzzled tone.

Fred Dore raised bis eyebrows. "Well, you see, it's like this. Joe Financier jumps from the twelfth story of the Hotel Exclusive. You've got to print that but you don't rub it in by saying that he was living in room 1205. People don t like to tuck into bed right on the heels of a tragedy. A room can get a black name. It may even be that the out of town buyer won t be too enthusiastic about Room 1203 or 1207 either.

"I never thought of that.

"As a matter of fact I once busted that rule myself and broke it wide open. You remember the Lawton murder in the Hotel Hinton?"

Stanley maintained a discreet silence and Keating shook bis head.

"I'm older than I thought, muttered Dore, "but I suppose a lot of blood and crime has flowed under the bridge since my day and it really wasn't so much of a murder. At least not for us. It was too grisly. We didn't have any tabloids to steal away the inhibitions. Don t tell me you don't remember the Hinton because that's still going, after a fashion. In my day everybody who thought he was a star actor or a great novelist lived there and the rest of the world dropped in to stare at them during lunch. Well, one evening a young man came to the desk and registered as John Howard and wife, because bis name was Thomas Conrad and hers was Miss Ethel Lawton. He turned out to be the son of an Ohio preacher and she bad once been in the chorus of a Broadway show.

"The details of the crime were what you might call just a little bit morbid. They had a late supper in the room and some time between one and half past four in the morning, he killed her with a steel knife from the table. Nobody heard any screams so probably the first thrust was fatal. But he was drunk and didn't know that. Jealousy was the motive and he was raging as well as drunk. That made things messy. Perhaps it was just the look of things that sobered him up or maybe he fell into a drunken stupor but, along about half past four he decided to make a run for it. The girl on the switchboard got a call, along about that time, from Room 813 complaining that the caller couldn't get any hot water from the tap."

"Cold would have been better for blood stains," said Keating.

"Yes, but that was among the things he didn't know and that was why he didn't get by the bellboy when he came down in the elevator and tried to saunter out the door to the street. I didn't get to the hotel until half past five in the morning and I had an eight o'clock deadline. And old man Hinton tried to give me the run around. He wouldn't let me go up to the room and he wouldn't give any details. I went away

from that murder good and mad and I wrote, 'Thomas Conrad, the son of a preacher, killed Ethel Lawton, the prominent showgirl, with a steel table knife in Room 813 of the Hotel Hinton early this morning.

"I just wanted to get square with Hinton. It did the trick. He had to re-number the entire hotel. He made 20 the lowest number on each floor and so 813 became 833 and for all I know that's what it is today."

Keating rose from the table. "Thanks for the jolly little anecdote, Fred, but I've got to go back to the office to sit at your old desk and hand out assignments. If you stick around for half an hour, I'll let you tell me some more bedtime stories."

When the city editor had gone, Stanley said solemnly, "Mr. Dore, how do you get to be a good reporter?"

"Are you kidding me?" asked Fred Dore.

"No, you see they don't give me assignments that are much good, on the Express. What can 1 do on my own?"

"Read the papers," said Dore, "and pick up some loose end that's been overlooked. Read the want ads. About twice a year a good yarn comes out of them. I can't wait for your boss. Kiss him for me and say that I'll be back again, sometime."

Three weeks (Continued on page 64) later Ralph Stanley read a want ad over for the second time and then walked to the desk. The ad ran: "Wanted mature level headed woman, ; college graduate preferred for night switchboard Hotel Hinton excellent salary. Apply in person at noon to Fred Hinton hotel office."

(Continued from page 24)

It was around eleven when he found ; Hinton in his little office just off the ] hotel lobby. "I'm a reporter from the Express," said Stanley, "and I wanted lo see you about this ad."

It had seemed to Stanley when he first came in that the old man at the desk had the reddest face he had ever | seen in his life. The next instant proved to him that he was wrong.

"You're all a bunch of peeping Toms," sputtered Hinton. "1 can't even hire a telephone operator without one of you coming around pestering me. What's strange about my hiring a telephone operator? It's that damn poker bunch I rented a room to, one of my best rooms. I'll throw 'em out today. I just don't want newspapermen hanging around the place."

Stanley withdrew before his fury. "What's biting him?" he wondered. "That won't make much of an interview." He was about to walk through the lobby into the street when he noticed on a bench a very old man in ! a bellboy's uniform. "That would he i Old Tom, the one who stopped Conrad

on account of the blood stains." He paused in front of him and asked suddenly, "How many girls have you had on the night switchboard in the last year?" And this time the reporter saw a man turn whiter.

"I really couldn't say, sir." he stammered. "You'd have to sec Mr. Hinton about that."

Stanley handed him a dollar. "How many?" he persisted.

"Really, I couldn't say. It would ho several. Yes, several."

"Could you get me the name and the address of the last one if 1 gave you five dollars?"

The name of the last operator turned out to he Mrs. Elizabeth Maitland. She was middle-aged, English and placid. In no way did she seem to meet the description of flighty.

"I really don't see what f have to talk about with a press man," she said when Stanley came into her tiny apartment. "It was just silly. That's all. Mr. Hinton means well, hut 1 told him twice that he ought to find out who's doing it even if he needs a detective. That just made him angry. He insisted that no such thing ever happened and that 1 was making it up. And under those circumstances 1 had to give up the job. I've got my self-respect no matter what the salary is."

(Continued on page 73)

(Continued from page 64)

"Well, just what did happen?"

"Well, it only happened twice in the month I was there. But I know it's happened before. They tell me there were nine different girls on that switchboard all in a year."

"You saw something, perhaps?"

"Oh, no, I never saw anything. It all sounds so silly to talk about. But he ought to have that switchboard fixed. No matter what Mr. Hinton says I'll swear there wasn't any flash on the board. It must come from the outside."

Stanley decided to let Mrs. Maitland tell her story in her own way.

"The first time was one morning after I'd been there a week. It was very quiet. There hadn't been any calls for an hour. There wouldn't be. It was about half past four in the morning when suddenly there's this voice in my ear. And mind you there's no buzz and no flash on the board. There couldn't be any flash on the board because I haven't got any such room number. It was a low voice like somebody who was excited trying to be calm and all it said was, 'This is Room number B13, and I can't seem to get any hot water out of the tap. Could you please send up a pitcher and hurry, please hurry.' Well, like a fool, I look for 813 to plug in and then I remember we haven't got any such number. Mr. Hinton explained to me that years ago he changed the numbers and began with twenty because lie didn't want to have thirteen anything on any floor because people are superstitious about it. There not being any flash, I'm naturally puzzled."

"What used to be 813 would now be 833. Did you think of that?" suggested Stanley.

"I did but there wasn't any help in that. Eight hundred and thirty-three is only used twice a week. It's reserved all the time for the Circle Club."

"But why were you so concerned about this call? This wasn't the first time you'd had anybody call up and kid you."

"It was something about the voice being so scared like. Besides when people call up to have you on they say, 'Sweetheart, when are we going to get married?' Or something like that. And they're drunk, of course, and laughing. And they don't whisper in a voice like that about a pitcher of hot water. And the board does flash the room number."

"But the call could have come from the outside."

"That night, yes, but not the second time. The second time I cut off the trunk lines and I still had the voice. But even that wasn't the thing which made me go to Mr. Hinton to complain. The first time it happened I never mentioned it to anyone."

"What happened the second time?"

"Well, this time it was exactly four thirty in the morning. It was just a week later. The voice said the same thing. It wanted a pitcher of hot water. 1 cut of! the trunk lines like I told you. And I still got the voice saying, 'Hurry, please hurry.' Now I hope I'm a lady and 1 suppose there's no excuse in what I said back to it. But you must remember how exasperated I was. I don't like to tell you what I said." Stanley kept silent secure in the belief

that Mrs. Maitland was caught up in the current of her narrative.

"It just came out all of a sudden. I snapped at it, 'You may think you're funny, but I think you're a bloody fool.' " Mrs. Maitland stopped again and there was a frozen look of horror on her face.

"It began to weep. Whatever it was it wasn't joking and it said in the most terrible voice, 'Yes, that's what I am, a bloody fool.' And then, the worst thing of all, it laughed, but you know— not funny. And then it whimpered, 'Hurry, please hurry and save a poor bloody fool from eternal damnation.'"

"Strange," said Stanley, "and pretty horrible."

"You may well call it horrid," replied Mrs. Maitland. "I've been a widow for seven years and I can take a joke with the best of them, but I'm not going to stay in any place where a voice that isn't larking can come out of the night and whisper in my ear profane and foul language like 'damnation' and 'bloody.'"

It was a week or so later when Keating greeted Stanley in the city room of The Express and said, "Young fellow,

I remember you were up at the Hotel Hinton a few days back looking for a feature story. Something about 'Did women make better telephone operators if they had a college education.' Well, we have a story about the Hinton now. I don't see how you could have caught it a week ago. It isn't much of a story and it is a little messy. Not exactly the thing for a family newspaper and besides I suppose we might as well give the hotel a break."

"What's happened?" asked Stanley.

"Oh," said the city editor, "it's just that a bellboy committed suicide in one of the rooms. There's no story in that, of course, but he did it in a curious way. It seems there's a poker crowd, The Circle Club, that meets at the Hinton in the same room once or twice a week. They have the custom of calling up ahead of time and ordering dinner so that everything is on the table when they get there. It was this time. But also on the table was the body of this bellboy, Thomas Collins, Old Tom they called him. It seems he's been with the hotel thirty-five or forty years. Yes, he was lying dead on the table. He'd cut his throat with a steel knife. They didn't play any poker that night. I guess they won't play any more poker in that room. Oh, of course, if we wanted to go in for morbid stuff, I suppose there might be a story in it, but the Hinton is an occasional advertiser and we might as well follow the general rule about minor hotel suicides and forget it."

He took the flimsy about the Hinton and jammed it on the spike before him. Then Stanley gave a startled cry for, on the mimeographed sheet of paper, he saw a spreading stain of red.

"What's the matter, kid?" said the city editor. "You look white. Don't worry. I just happened to cut my hand when I jammed that story down on the spike. It's bleeding. Still, I've killed the story of room 833 and I suppose every story, just like every person, has some blood in it. What could be fairer than that?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now