Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe grand guillotine of Paris

JANET FLANNER

Anatole-Joseph-François Deibler, Grand

Guillotiner of France, is one of the few high officials who hasn't been shifted from his job in the recent Parisian political shakeup. He is seventy-two years old, a handsome, humorless, taciturn, well-to-do suburbanite, the third generation in a hereditary dynasty of executioners. Owing to a custom that pre-dates the execution of Louis XVI, he is called Monsieur de Paris. Owing to a custom that post-dates the execution of Marie-Antoinette, La Veuve Capet, the guillotine is called The Widow. The aides who assist Monsieur de Paris and The Widow in their fatal work are called The Valets. And while, as elsewhere, the death penalty in France is the property of the State, the guillotine is the private property of the Deibler family and is handed down (with repairs) from father to son.

The current Monsieur de Paris owns two Widows—a heavier machine for executions in Paris, and a lighter, more up-to-date model for use in the provinces. Both are equipped with every humane improvement —wheels on which the knife descends faster than in the old-fashioned soaped grooves, and modern shock-absorbers. But in her general set-up, The Widow hasn't changed since the French Revolution.

In the dim dawn of a city street, the guillotine still looks like a tall and narrow window, set up in the wrong place andgiving onto nothing. The wooden side-posts which compose the frame weigh seventyfive kilos each and are one and a half times the width of a man's neck apart. They stand approximately fifteen feet high, and are topped in the crossbar by a trigger-set weight of forty kilos, into which the sevenkilo blade is fixed at the last minute before an execution. The weight and blade are sent rushing down by a turn of the declic—a kind of door-knob set in one of the side-posts and connected by pulleys with overhead springs which sustain the weight. Since it sends a man off on his final journey, this weight is termed the sac a voyage, or travelling-bag. The blade itself is obliquely edged, and is made of steel and bronze in Langres, the cutlery center of France. When not in use, it is kept in vaseline; and as a result of such solicitous treatment it lasts for many years, and is never honed.

The guillotines used to be stored in an old barn on the outer boulevards. Now, they are kept nearer at hand in the Prison de la Sante, not far behind the Cafe du Dome, in Montparnasse. By French law, executions are theoretically public, taking place at dawn, the legal hour, in deserted streets or town squares. For a Paris beheading, the large Widow is trundled out of the Prison about three hours before dawn, around the corner to the Boulevard Arago, in a little old black van that looks so much like a Punch and Judy wagon that it is nicknamed le guignol. This van is horse-drawn on iron-rimmed wheels and is lighted by a swinging petrol lantern.

It takes about an hour to set up the guillotine. Each piece is numbered, and the whole is so perfect, mechanically, that it can be assembled in complete silence without even the blow of a hammer. As Deibler is now an old man, his first Valet superintends the job; but, as chief, and despite his age, Deibler fixes the knife to the sac a voyage at the last minute, and hoists them both—a weight of about a hundred pounds—to the crossbeam. Occasionally a trial decapitation is made with a roll of hay, to make sure that everything is working smoothly.

About ninety minutes before dawn, Deibler and his first and second Valets drive back to the Prison for their victim. The prisoner does not know that his last hour has come, until they enter his ceil with his lawyer, a priest, and the prison warden, who says, "Ayez courage." He is given a glass of rum, and a prayer is said.

The condemned man is then led outside to the guignol. He is usually clad in his best trousers, silk socks, and well-shined shoes. His shirt is cut away in back over his shoulders, his neck clipped of hair, and his hands tied tightly behind him—the knot being looped vertically to the looser one which binds his feet. A little later, in the Boulevard Arago, this will make him walk his last few steps toward The Widow with his head high, the proud pose being ironically the easiest at his ending.

As he stumbles out of the guignol toward the guillotine, the priest marches in front of him, fantailing his black skirt so as to hide the horrid instrument from the prisoner. The Garde Repiiblicaine, drawn up on horseback in a square around the machine, raise their sabres in a final salute of honor for the soon-dead man. Behind the Garde, the lines -of policemen begin to cross themselves. In the background, a crowd of citizen onlookers keeps an intuitive silence, although the vital happening of the execution is invisible to them. ... A murderer is beheaded, and he will be buried, according to law, in an unmarked grave in ground supplied by the State. Monsieur de Paris has done his job.

The Deiblers are one of the two famous executioner families of which France has been proud. Curiously enough, the origin of neither family was French. The Sansons, who chopped their way to fame for six generations from 1664 through the Revolution, and until about 1850, were Italian in origin, and of little character-interest. The Deiblers, who succeeded the Sansons, were German, but the facts of their three generations would make up a Turgenev trilogy.

(Continued on following page)

Joseph Deibler, the clan founder, was a farmer, born in Bavaria in 1783, wrho drifted to France in the Napoleonic era. In 1820, finding himself penniless, he became Valet at Dijon to Desmouret, chief executioner of Burgundy. Slightly mystical, and with a farmer's imperviousness to butchery, he apparently decided that he had been appointed by God to a perpetual Valetship, since, thirty-three years later, at the age of seventy, he turns up again as Valet to the chief executioner in Algeria, Rasseneux. Rasseneux had no son fas much of a misfortune for an executioner as for a king), but he had one daughter, Zoe. A marriage was made for Zoe and Louis Deibler, Joseph's son and heir. Louis was timid, club-footed, and only thirty years old. But he was obedient and ambitious, and was consequently named second Valet and heir-apparent to Rasseneux, his fatherin-law.

Old Joseph Deibler had, therefore, founded what he considered to be the divine Deibler dynasty. As proof of its divinity, God (and Napoleon III) appointed him, five years later, at the age of seventy-five, to be chief headsman of Brittany—or, Monsieur de Rennes, Rennes being the principal city of Brittany. Chief executioners had been city-titled since about 1778, when the seven Sanson brothers— head-choppers all over France—began calling themselves Monsieur de Versailles, Monsieur de Blois, etc., to avoid confusion. As Monsieur de Rennes, Joseph Deibler's Teutonic haughtiness finally flowered; he decapitated his French victims with the scorn of an avenging angel. He despised his neighbors' horror of him—their horror of Louis, now his father's Valet, and their horror of Louis' wife. And he knew he was right when God sent Louis and Zoe a son, Anatole-Joseph-Frangois, Grand High Executioner of All France today.

As successor to his father at Rennes, Louis Deibler was a sinister buffoon. Sensitive about his deformity, and at the same time conscious of his own good education, he suffered beneath the ostracism that was put upon him, his wife, and his children. When he went forth to conduct an execution, he dressed like a morbid scarecrow, in his battered plug hat, disreputable redingote, and with the giant umbrella which he used as a cane. What he liked to do was to stay home and model little clay figures of dancing women.

So, for nearly forty years, Louis Deibler limped around France, dealing death with no esoteric conviction that he had been appointed by God. Though a clumsy executioner—he lacked the swift, sure style of his father and his son—he was, to his surprise and all the other provincial headsmen's fury, named Monsieur de Paris in 1871. And at this time, moreover, the economizing Third Republic put an end to all local executionerships, making the office national.

In Paris, Louis Deibler took to playing cards in Auteuil cafes and later to religion, always putting on his gloves to take Communion, where other men took theirs off. In 1898, when executing the "toadstool murderer," Carrara, he suddenly screamed for water, crying, "I am covered with blood!" He had succumbed to the dreadof-blood delusion that frequently seizes butchers and surgeons and is now known as hemophobia. Lady Macbeth had called it "Out, damned spot!"

On New Year's Day of the following year came the Chancellery's appointment of Louis' son, Anatole, as Monsieur de Paris. Louis, though never cut out for the work, had assisted at more than a thousand executions, had performed one hundred and eighty as chief. He died in 1904, bequeathing to his son 400,000 gold francs and the family guillotine.

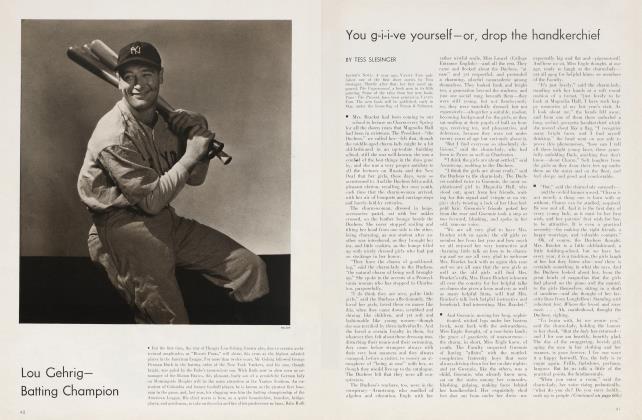

Anatole Deibler, still the incumbent today, is in no sense an eccentric. He divides his time between cinemas, travel, motoring, trout-fishing at his small country place on the Cher, and rose-gardening at his even smaller Paris home at 39, rue ClaudeTerrasse, near the Porte St. Cloud. He has spent his life hoping to be treated as other men are treated, although doing what they are forbidden to do.

After finishing school at the Rennes Lycee, he tried to dodge his fate by working in a Paris department store. He persuaded the State to let him undertake military service, though headsmen's sons had been exempt since 1832. Four years of suffering as the barracks' butt brought him the nickname Chin-Chopper. Embittered, he went to Algiers and took up the family burden, becoming Valet to his old grandfather, Rasseneux. (Executioners are peculiarly long-lived.)

• At the age of thirty, Anatole returned to Paris to be his father's Valet. The carpenter who made the guillotines (the Deiblers have sold three to China at seven thousand francs apiece, and one is still operating today in the central prison at Peiping) refused to let his daughter marry the young executioner. In the meanwhile, he had taken up fast bicycle-riding and had joined the Societe Velocepedique d'Auteuil (his name appears on the Societe's early programs as a sprint hope). In the tandem events he met his final partner, a petty government employee, Mademoiselle Rosine Rogis. They were married in 1898, the year before Anatole was appointed Monsieur de Paris. One little son was born to the Anatole Deiblers. He lived for only a month, dying, ironically, from the poisonous prescription of a careless chemist. Deibler refused to bring suit. Then a daughter was born, Marcelle, still the apple of her father's eye. When Obrecht, Anatole's second Valet, asked for Marcelle's hand, Madame de Paris said she would rather see her daughter dead than married to an executioner. So Obrecht married a schoolteacher; and today, Marcelle, in her spinster thirties, drives her father around in the family Citroen. She and her mother do the housework. Deiblers can't keep servants.

But despite his ambition to be looked upon as an ordinary French citizen Anatole Deibler is a mystery man to most of France. Few but his neighbors and the criminals he executes know him by sight. Because people are either horrified or fascinated by him, the Deiblers have no friends. They have nothing but business associates. On Sunday nights, second Valet Obrecht drops in to drink a weekly Pernod. On Sunday noons, the Deiblers lunch with the Desfourneaux, who are first, third and fourth Valets. The Desfourneaux are connected by marriage with Madame Deibler's family and are themselves from an older clan of executioners than the Deiblers, but one not so renowned. Leopold Desfourneaux, an uncle, who was also a Deibler Valet, couldn't kill a Sunday chicken for stew and was afraid of spiders.

Continued on page 62

Continued from page 22

The Valets can afford to behead only as a side-line, as the job is so ill-paid. Deibler's four Valets receive, respectively, twelve thousand, ten thousand eight hundred, seven thousand two hundred, and six thousand francs, annually. Deibler himself is paid only eighteen thousand francs a year, besides the ten thousand francs for upkeep of The Widow, who needs nothing but cheap vaseline and a little paint.

When Deibler is executing in provincial prisons, the smaller guillotine and guignol ride free on a flat car on the same train with him. On one occasion, he lost them for three days, and the two condemned criminals, whom he had travelled a long distance to execute, were pardoned, because the legal hour for their deaths had passed by.

Deibler and his Valets all travel together in a second class compartment, reserved by the Authorities of Justice; the blinds are pulled down, and no one is allowed to disturb the occupants. At the local hotel Deibler registers as F. Boyer, Travelling Man from Arras. One necessary item in his travelling equipment is an alarm clock, since an Albi hotel-keeper once forgot to arouse him in time to perform an execution. He also takes a revolver along with him, as headsmen have been repeatedly shot at when executing anarchists.

After thirty-six years as the only national headsman working in Western Europe, Deibler is tired and cardiac. He tried to resign a few years ago, before the execution of Gourgulov, assassin of President Doumer; his resignation was accepted, on the condition that he pass up the full-pay pension which French executioners have always drawn. He is still working. Executioners, since they have little else that is pleasantly worldly in their lives, like money. Deibler permitted Obrecht, his second Valet, to turn the declic for Gourgulov's head, as a sign of his own retreat and as a mark of his dynastic selection, since he has no son. The oldest Desfourneaux, Anatole's first Valet, is entitled to inherit the job, but he is middle-aged, easy-going, and hates responsibility. Obrecht will probably be appointed the future Monsieur de Paris.

Except for the Deiblers, the other great guillotine families of the 19th Century have disappeared completely from the scene. One of the Desmourets, the Limoges headsman, starved to death after the 1871 ruling which deprived him of his provincial position. After the same ruling, Guinheisen, Monsieur de Caen, put his money into land, and became an important farmer. A descendant of the Sanson tribe is now a clerk in the Ministry of Justice. Headsmen used to make fortunes—old Louis got sixty thousand francs annually—but Anatole Deibler now makes very little, and is prevented by society from spending that easily.

His stoical, courageous attitude toward his job has done much to satisfy the French people in regard to their method of capital punishment. It appears to be a sensible, economical, and probably painless guarantee of protection for modern society. Deibler does not think of himself as a divine instrument, but as a lonely cog in a large legal machine. Fie says that he is set in motion by tbe jury that votes, by the judge that condemns, and by the President of the Republic who fails to grant a pardon. Like them, he is guiltless of blood. But his neighbors will dine with the jurymen, the judge, and especially with the President. They will not dine with Anatole Deibler.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now