Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe rise of the dark stars

ROBERT SCOTT McFEE

When the S. S. Whatsis steams out of New York Harbor with a cargo of Olympic athletes, Berlin bound next summer, it will probably carry the largest shipment of Aframerican athletes ever to compete for the United States at one time. The colored brethren have suddenly begun to scuttle over the ground at amazing rates of speed, leap tremendous distances, and fly into the air over the high jump bar at record heights. The papers are suddenly full of the doings of colored athletes and star after star has come along, apparently all at once. There are Eulace Peacock and A1 Threadgill of Temple; Cornelius Johnson, the high jumper from Los Angeles; Ben Johnson, the Columbia University sprinter; Ralph Metcalfe, no newcomer, but still an able hangover from the last Olympic games; Willis Ward, the Michigan star; and the latest, Jesse Owens, the Cleveland schoolboy. Not to mention that big athlete from Detroit, Joe Louis, who is out to win himself the heavy-weight boxing championship of the world and probably will.

Is there any reason for this sudden rising tide of color in sport? There is not. Is it a coincidence? Is there some mysterious something about the physique of our black brother that he possesses exclusively, and which causes him to run faster and jump higher and farther than his white colleague? Is he closer to Pithecanthropus Erectus, and therefore stronger, quicker and more nimble than his-more decadent white brother? The answer to both of them is "no." Then what has suddenly occurred to account for this slew of great sepia-tinted athletes? Harriet Beecher Stowe is still good authority on that. Like Topsy, they jest growed.

There is a popular legend that these descendants of the children of the jungle are, of necessity, better built, better muscled, more agile, and more powerful than the white races. But it isn't true. Muscles, speed, coordination and skill are acquired by training and coaching, and not by heredity. Look at the picture of the average African warrior, or young man, in the motion pictures or in still photographs, and he is far from looking like an athlete. Usually he is potbellied, stoop-shouldered, with poor posture, his bones are badly formed and he has been ravaged by all kinds of illnesses. What is probably more true than those current legends and ideas about the physical superiority of the black man is that if you went into the African jungle, and imported the ten best-looking physical specimens to America and lined them up on scratch, there wouldn't he a single schoolboy "Century" runner who wouldn't beat them ten yards in a hundred.

Outside of the pigmentation of the skin, there are no structural differences in bone or muscle in white man or dark. But, properly trained and developed, the Negro body can be built up into a beautiful thing, perhaps more beautiful sculpturally than the white man's. But even here there may be an illusion. The tan, brown, black or bronze skin accepts highlights so much more gracefully and effectively than the vapid pink flesh of the pale faces.

For that matter, the American Indian, a true aborigine, a real child of nature, born, bred and inured to hardship, should, by rights of all the legends about the superiority of the people and races closest to nature, have made magnificent athletes when finally they were tamed, sent away to school and taught how to play the games of the white world. Those games, all of them, should have been pushovers for these strong and wiry redskins. But they weren't. There has been only one truly great Indian athlete, and that was Jim Thorpe. The Carlisle Indian football team once cut a few didoes back in the days of turtle-necked sweaters, and Yale men who wore their hat brims pinned up in front, but that was because they had a master strategist and general to teach them and lead them. His name was Glenn Warner. And they haven't been heard from since.

But the transplanted African is another matter, especially if he has been transplanted to the Northern states, the Middle West, or the Coast. In the first place, his circumstances are such (usually povertystricken) that at an early age he is doing severe manual labor, which hardens his body and develops his muscles. And likewise in those sections, under the benevolent democracy of the public-school system, he starts on even terms with the white children. He runs races against them in the school yard, does the same exercises, plays the same games and receives the same elementary instruction. It ought to begin to show results. It has.

All of the new crop of Negro stars are Northern or Western men. Eulace Peacock, the Temple University Pentathlon star comes from Lancaster, Pa. Ben Johnson, Columbia sprinter, is from Plymouth, Pa. Cornelius Johnson hails from Los Angeles. Willis Ward is from Michigan, and Jesse Owens is from Cleveland. Metcalfe and Tolan, too, are Middle Westerners. No great colored athletes come out of the South that I know of. And what is more, no great colored athlete, or Negro athletes at all, come out of those parts of Africa that have French or English protectorates, simply because they have no help and no teaching. They may be the greatest raw material in the world, but raw material always remains raw until somebody works it, and develops it into a finished product. Now the grammar schools and high schools of the North are getting their percentages of Negro population, and the Negroes are developing normally and having their proper percentages of star athletes as have the Jews, the Italians, the Irish, the Poles and the Slovaks, and all the other American melting pot mixtures. It goes in cycles, usually. At present the colored men are on the upswing of the wheel.

Continued on page 57

Continued from page 50

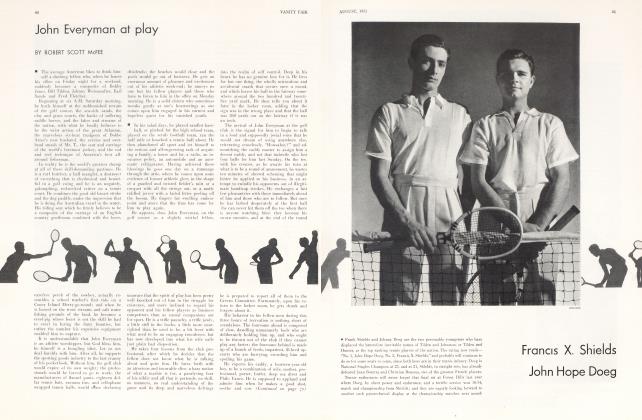

The current group of Negro stars includes some great performers, boys who will find themselves wearing the shield of the United States in Berlin next summer, if only they repeat their performances of this year without ever improving. Cornelius Johnson, for instance, light skinned, tall—he is six feet, three in height,—has already done six feet, eight and five-eighths inches in the high jump, tying Walter Marty, another great California jumper. He is pointing for entrance to the University of Southern California. He feels sure that he will high-jump six feet, ten inches. Marty is the present world's record holder with 6 feet, 9⅛ inches. Johnson has still seven-eighths of an inch to go. He probably will make it because he is still only a youngster. He uses the Western roll to wriggle over the bar, and, incidentally, runs at the bar from the right-hand lane the way Marty does.

Jesse Owens, now a sophomore at Ohio State, did most amazing things with his legs all in one afternoon of the Western Conference Championships last May. First, he tied Frank Wykoff's record Century of 9.4 seconds. Then, in two hours time, he broke three world's records in a row. He sailed 26 feet, 8¼ inches to break the Japanese Nambu's broad-jump record. Next, he shaved three-tenths of a second from Roland Locke's "220" record of 20.6, and to top off the afternoon, he fled nimbly over the 220 yard hurdles in 22.6 seconds—2/5 of a second under Charlie Brookins's mark. For one pair of legs, it was the greatest afternoon since Marathon.

Ralph Metcalfe is still probably the greatest sprinter in the country, though it looks as though he will have to beat Owens in the Olympic trials, but Ben Johnson, the Columbia Negro, showed his promise in the last indoor season when he beat Metcalfe in one of the qualifying heats of the 60 yard dash. True, Metcalfe beat him in the finals, but Johnson is improving all the time.

Eulace Peacock, the Temple University Pentathlon star, wins his championships mainly with his speed, since he started as a sprinter. When he won the National Pentathlon championship last year, his placings to win a score of 3,258.46 were as follows: He was first in the 200 meter dash, in record time, and first in the broad-jump. He placed third in the javelin throw, fifth in the discus, and last in the 1,500 meter run. Practically all of the sprinters now are broadjumping, too, since it was established that the jumping was not injurious to their sprinting muscles.

Willis Ward, the Michigan football player, is a six footer, weighing 196 pounds. But he has high-jumped over six feet, eight inches, and equalled the world's record indoors for the 60 yard dash. He also runs the hundred and the hurdles and broad-jumps. In addition, he was that real rarity, a good Negro football player. He was AllConference End, for two years, and one of the trickiest wingmen the Middle West has ever seen. A southern football team protested against playing against him last year and the entire campus was up in arms for him. There was a ticklish situation for a little while until an intelligent newspaperman persuaded both the authorities and Ward that it would be foolish to endanger his marvelous chances for a track career by having him crippled on a football field.

In prizefighting, the strong and intelligent Negro with good reactions can hold his own with any man in the world. Here again are false legends, namely, that he is cowardly and unwilling to face punishment, and that he is unable to assimilate a blow in the stomach. I have seen hundreds of prizefights featuring both Negroes and white men, and the truth of the matter is that there are quitters and boxers without heart in the ranks of the white as well as the black, and the poorly conditioned or too imaginative white man is just as prone to roll over and play dead doggie from a punch in the stomach as is the colored boy. And on the other hand I have seen examples of magnificent bravery and willingness to take punishment on the part of Negro fighters, and I have seen their stomachs punched until every one in the house but they winced at each blow. And they didn't quit.

Some of the greatest ring fighters the world has ever known have been Negroes. Sam Langford was one. Jack Johnson was another. Certainly he was the greatest Negro boxer. Men who have seen Joe Cans fight say they haven't seen a lightweight since. And now the sensational rise of Joe Louis of Detroit indicates another to go in this gallery—if he makes the grade. But if he does become heavyweight champion of the world, or does become a great fistic star, it will not be because he is a Negro and therefore has some special qualities, but because he merely happened through special training to have acquired those attributes necessary to the success of a professional prizefight champion, be he white, black, red, yellow or plaid. The ignorant whites and the ignorant darkies love to get themselves embroiled in a little riot or blood-letting over the merits and supremacies of the two races as based on the performance of a white man against a black man in a heavyweight championship prizefight, and nothing, of course, could be more fallacious. For the ring, like a forty-five pistol, makes all men equal and, in it, muscles count, not hue.

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now