Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

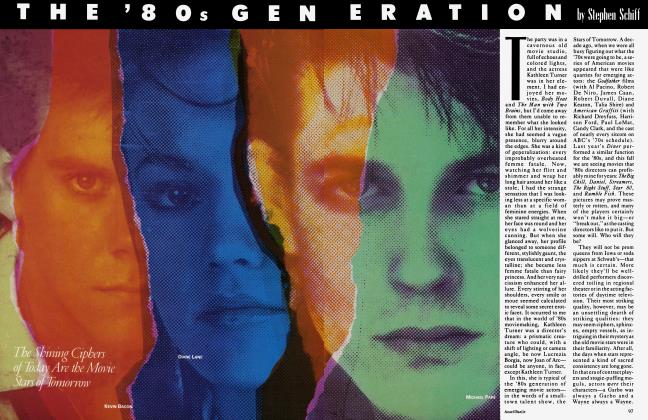

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Passion of poets

a Time... worships language and forgives Everyone by whom it lives. "

WH. Auden

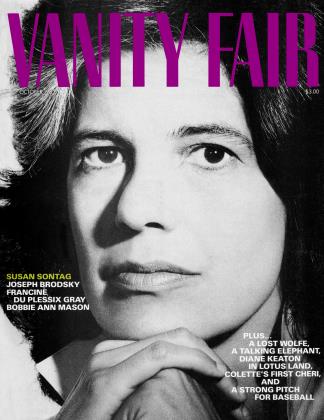

WH Auden was called by some the greatest living poet in the English language. Joseph Brodsky has been called the finest Russian poet of his generation. On the tenth anniversary of Audens death observed in New York this month in a weeklong tribute to the poet, Joseph Brodsky writes a moving recollection of the man "through whom the truth made itself audible. In turn, Susan Sontag in her afterword to Brodsky's tribute, writes a challenging analysis of what Russian (and other) poets of this century have achieved, not only only in in poetry pc but in poets prose "

When a writer resorts to a language other than his mother tongue, he does so either out of necessity, like Conrad, or because of burning ambition, like Nabokov, or for the sake of greater estrangement, like Beckett. Belonging to a different league, in the summer of 1977, in New York, after living in this country for five years, I purchased in a small typewriter shop

on Sixth Avenue a portable "Lettera 22" and set out to write (essays, translations, occasionally a poem) in English for a reason that had very little to do with the above. My sole purpose then, as it is now, was to find myself in closer proximity to the man whom I considered the greatest mind of the twentieth century:

Wystan Auden.

I was, of course, perfectly aware of

the futility of my undertaking, not so much because I was born in Russia and into its language (which I'll never abandon—and I hope vice versa) as because of this poet's intelligence, which in my view has no equal. I was aware of the futility of this effort, moreover, because Auden had been dead four years then. Yet to my mind, writing in English was the best way to get near him, to work on his terms, to be judged if not by his code of conscience, then by whatever it is in the English language that made this code of conscience possible.

These words, the very structure of these sentences, all show anyone who has read a single stanza or a single paragraph of Auden's how I fail. But, to me a failure by his standards is preferable to a success by others'. Besides, I knew from the threshold that I was bound to fail; whether this sort of sobriety is my own or has been borrowed from his writing, I can no longer tell. All I hope for while writing in his tongue is that I won't lower his level of mental operation, his plane of regard. This is as much as one can do for a better man: to continue in his vein; this, I think, is what civilizations are all about.

I knew that by temperament and otherwise, I was a

different man, and that in the best case possible I'd be regarded as his imitator. Still, for me that would be a compliment. Also I had a second line of defense: I could always pull back to my writing in Russian, of which I was pretty confident and which even he, had he known the language, probably would have liked. My desire to write in English had nothing to do with any sense of confidence, contentment, or comfort; it was simply a desire to please a shadow. Of course, where he was by then, linguistic barriers hardly mattered, but somehow I thought that he might like it better if I made myself clear to him in English. (Al-

though when I tried, on the green grass at Kirchstetten eleven years ago now, it didn't work; the English I had at that time was better for reading and listening than for speaking. Perhaps just as well.)

To put it differently, unable to return the full amount of what has been given, one tries to pay back at least in the same coin. After all, he did so himself,

all, he did so himself,

borrowing the "Don Juan" stanza for his "Letter to Lord Byron" or hexameters for his "Shield of Achilles." Courtship always requires a degree of self-sacrifice and assimilation, all the more so if one is courting a pure spirit. While in flesh, this man did so much that belief in the immortality of his soul becomes unavoidable. What he left us with amounts to a gospel which is both

brought about by and filled with love that's anything but finite—with love, that is, which can in no way all be harbored by human flesh and which therefore needs words. If there were no churches, one could have easily built one upon this poet, and its main precept would run something like his

If equal affection cannot be,

Let the more loving one be me.

If a poet has any obligation toward society, it is to write well. Being in the minority, he has no other choice. Failing this duty, he sinks into oblivion. Society, on the other hand, has no obligation toward the poet. A majority by definition, society thinks of itself as having other options than reading verses, no matter how well written. Its failure to do so results in its sinking to that level of locution by which society falls easy prey to a demagogue or a tyrant. This is society's equivalent of oblivion; a tyrant, of course, may try to save his society from it by some spectacular bloodbath. I first read Auden some twenty years ago in Russia

in rather limp and listless translations that I found in an anthology of contemporary English poetry subtitled "From Browning to Our Days." "Our Days" were those of 1937, when the volume was published. Needless to say, almost the entire body of its translators along with its editor, M. Gutner, were arrested soon afterward, and many of them perished. Needless to say, for the next forty years no other anthology of contemporary English poetry was published in Russia, and the said volume became something of a collector's item.

One line of Auden in that anthology, however, caught my eye. It was, as I learned later, from the last stanza of his early poem "No Change of Place," which described a somewhat claustrophobic landscape where "no one goes / Further than railhead or the ends of piers, / Will neither go nor send his son... " This last bit, "Will neither go nor send his son..." struck me with its mixture of negative extension and common sense. Having been brought up on an essentially emphatic and self-asserting diet of Russian verse, I was quick to register this recipe whose main component was self-restraint. Still, poetic lines have a knack of straying from the context into universal significance, and the threatening touch of absurdity contained in "Will neither go nor send his son" would start vibrating in the back of my mind whenever I'd set out to do something on paper.

JOSEPH BRODSKY

TO PLEASE A SHADOW

A PASSION OF POETS

This is, I suppose, what they call an influence, except that the sense of the absurd is never an invention of the poet but is a reflection of reality; inventions are seldom recognizable. What one may owe here to the poet is not the sentiment itself but its treatment: quiet, unemphatic, without any pedal, almost en passant. This treatment was especially significant to me precisely because I came across this line in the early '60s, when the Theater of the Absurd was in full swing. Against that background, Auden's handling of the subject stood out not only because he had beaten a lot of people to the punch but because of a considerably different ethical message. The way he handled the line was telling, at least to me: something like "Don't cry wolf" even though the wolf's at the door. (Even though, I would add, it looks exactly like you. Especially because of that, don't cry wolf.)

Although for a writer to mention his penal experiences—or for that matter, any kind of hardship—is like dropping names for normal folk, it so happened that my next opportunity to pay a closer look at Auden occurred while I was doing my own time in the North, in a small village lost among swamps and forests, near the polar circle. This time the anthology that I had was in English, sent to me by a friend from Moscow. It had quite a lot of Yeats, whom I then found a bit too oratorical and sloppy with meters, and Eliot, who in those days reigned supreme in Eastern Europe. I was intending to read Eliot.

But by pure chance the book opened to Auden's "In Memory of W. B. Yeats." I was young then and therefore particularly keen on elegies as a genre, having nobody around dying to write one for. So I read them perhaps more avidly than anything else, and I frequently thought that the most interesting feature of the genre was the authors' unwitting attempts at selfportrayal with which nearly every poem "in memoriam" is strewn—or soiled. Understandable though this tendency is, it often turns such a poem into the author's ruminations on the subject of death from which we learn more about him than about the deceased. The Auden poem had none of this; what's more, I soon realized that even its structure was designed to pay tribute to the dead poet, imitating in a reverse order the great Irishman's own modes of stylistic development, all the way down to his earliest: the tri-

meters of the poem's third—last—part.

It's because of these trimeters, in particular because of eight lines from this third part, that I understood what kind of poet I was reading. These lines overshadowed for me that astonishing description of "the dark cold day," Yeats's last, with its shuddering

The mercury sank in the mouth of the dying day.

They overshadowed that unforgettable rendition of the stricken body as a city whose suburbs and squares are gradually emptying as if after a crushed rebellion. They overshadowed even that statement of the era

.. .poetry makes nothing happen...

They, those eight lines in trimeter that made this third part of the poem sound like a cross between a Salvation Army hymn, a funeral dirge, and a nursery rhyme, went like this:

Time that is intolerant Of the brave and innocent,

And indifferent in a week To a beautiful physique,

Worships language and forgives Everyone by whom it lives;

Pardons cowardice, conceit,

Lays its honours at their feet.

I remember sitting there in the small wooden shack, peering through the square porthole-size window at the wet, muddy dirt road with a few stray chickens on it, half believing what I'd just read, half wondering whether my grasp of English wasn't playing tricks on me. I had there a veritable boulder of an English-Russian dictionary, and I went through its pages time and again, checking every word, every allusion, hoping that they might spare me the meaning that stared at me from the page. I guess I was simply refusing to believe that way back in 1939 an English poet had said, "Time.. .worships language," and yet the world around was still what it was.

But for once the dictionary didn't overrule me. Auden had indeed said that time (not the time) worships language, and the train of thought that statement set in motion in me is still trundling to this day. For "worship" is an attitude of the lesser toward the greater. If time worships language, it means that language is greater, or older, than time, which is, in its turn, older and greater than space. That was how I was taught, and I indeed felt that way. So if time—which is synonymous with, nay, even absorbs deity—worships language, where then does language come from? For the gift is always smaller than the giver. And then isn't language a repository of time? And isn't this why time worships it? And isn't a song, or a poem, or indeed a speech itself, with its caesuras, pauses, spondees, and so forth, a game language plays to restructure time? And aren't those by whom language "lives" those by whom time does too? And if time "forgives" them, does it do so out of generosity or out of necessity? And isn't generosity a necessity anyhow?

Short and horizontal as those lines were, they seemed to me incredibly vertical. They were also very much offhand, almost chatty: metaphysics disguised as common sense, common sense disguised as nursery rhyme couplets. These layers of disguise alone were telling me what language is, and I realized that I was reading a poet who spoke the truth—or through whom the truth made itself audible. At least it felt more like truth than anything else I managed to figure out in that anthology. And perhaps it felt that way precisely because of the touch of irrelevance that I sensed in the falling intonation of "forgives / Everyone by whom it lives; / Pardons cowardice, conceit, / Lays its honours at their feet." These words were there, I thought, simply to offset the upward gravity of "Time. . .worships language."

I could go on and on about these lines, but I could do so only now. Then and there I was simply stunned. Among other things, what became clear to me was that one should watch out when Auden makes his witty comments and observations, keeping an eye on civilization no matter what his immediate subject (or condition) is. I felt that I was dealing with a new kind of metaphysical poet, a man of terrific lyrical gifts, who disguised himself as an observer of public mores. And my suspicion was that this choice of mask, the choice of this idiom, had to do less with matters of style and tradition than with the personal humility imposed on him not so much by a particular creed as by his sense of the nature of language. Humility is never chosen.

I had yet to read my Auden. Still, after "In Memory of W. B. Yeats," I knew that I was facing an author more humble than Yeats or Eliot, with a soul less petulant than either, while, I was afraid, no less tragic. With the benefit of hindsight I may say now that I wasn't altogether wrong, and that if there was ever any drama in Auden's voice, it wasn't his own personal drama but a public or existential one. He'd never put himself in the center of the tragic picture; at best he'd acknowledge his presence at the scene. I had yet to hear from his very mouth that "J. S. Bach was terribly lucky. When he wanted to praise the Lord, he'd write a chorale or a cantata addressing the Almighty directly. Today, if a poet wishes to do the same thing, he has to employ indirect speech." The same, presumably, would apply to prayer.

As I write these notes, I notice the first person singular popping its ugly head up with alarming frequency. But man is what he reads; in other words, spotting this pronoun, I detect Auden more than anybody else: the aberration simply reflects the proportion of my reading of this poet. Old dogs, of course, won't learn new tricks, but dog owners end up resembling their dogs. Critics, and especially biographers, of writers with a distinctive style often adopt, however unconsciously, their subjects' mode of expression. To put it simply, one is changed by what one loves, sometimes to the point of losing one's entire identity. I am not trying to say that this is what happened to me; all I seek to suggest is that these otherwise tawdry I's and me's are, in their own turn, forms of indirect speech whose object is Auden.

For those of my generation who were interested in poetry in English—and I can't claim there were too many of them—the '60s was the era of anthologies. On

the way home, foreign students and scholars who'd come to Russia on academic exchange programs would understandably try to rid themselves of extra weight, and books of poetry were first to go. They'd sell them, almost for nothing, to secondhand bookstores, which subsequently would charge extraordinary sums if you wanted to buy them. The rationale behind these prices was quite simple: to deter the locals from purchasing these Western items; as for the foreigner himself, he would obviously be gone and unable to see the disparity.

Still, if you knew a salesperson, as one who frequents a place inevitably does, you could strike the sort of deal every book-hunting person is familiar with: you'd trade one thing for another, or two or three books for one, or you'd buy a book, read it, and return it to the store and get your money back. Besides, by the time I was released and returned to my hometown, I'd gotten myself some sort of reputation, and in several bookstores they treated me rather nicely. Because of this reputation, students from the exchange programs would sometimes visit me, and as one is not supposed to cross a strange threshold empty-handed, they'd bring books. With some of these visitors I struck up close friendships, because of which my bookshelves gained considerably.

I liked them very much, these anthologies, and not for their contents only but also for the sweetish smell of their bindings and their pages edged in yellow. They felt so American and were indeed pocket-size. You could pull them out of your pocket in a streetcar or in a public garden, and even though the text would be only a half or a third comprehensible, they'd instantly obliterate the local reality. My favorites, though, were Louis Untermeyer's and Oscar Williams's—because they had pictures of their contributors that filled one's imagination in no less a way than the lines themselves. For hours on end I would sit scrutinizing a smallish, black-and-white box with this or that poet's features, trying to figure out what kind of person he was, trying to animate him, to match the face with his half or a third understood lines. Later on, in the company of friends we would exchange our wild surmises and the snatches of gossip that occasionally came our way and, having developed a common denominator, pronounce our verdict. Again with the benefit of hindsight, I must say that frequently our divinations were not too far off.

That was bow I first saw Auen's face"

A PASSION OF POETS

That was how I first saw Auden's face. It was a terribly reduced photograph—a bit studied, with a too didactic handling of shadow: it said more about the photographer than about his model. From that picture, one would have to conclude either that the former was a naive aesthete or the latter's features were too neutral for his occupation. I preferred the second version, partly because neutrality of tone was very much a feature of Auden's poetry, partly because antiheroic posture was the idee fixe of our generation. The idea was to look like everybody else: plain shoes, workman's cap, jacket and tie, preferably gray, no beards or mustaches. Wystan was recognizable.

Also recognizable to the point of giving one the shivers were the lines in "September 1, 1939," ostensibly explaining the origins of the war that had cradled my generation but in effect depicting our very selves as well, like a black-and-white snapshot in its own right.

I and the public know What all schoolchildren learn,

Those to whom evil is done Do evil in return.

This four-liner indeed was straying out of context, equating victors to victims, and I think it should be tattooed by the federal government on the chest of every newborn, not because of its message alone but because of its intonation. The only acceptable argument against such a procedure would be that there are better lines by Auden. What would you do with:

Faces along the bar Cling to their average day:

The lights must never go out,

The music must always play,

All the conventions conspire To make this fort assume The furniture of home;

Lest we should see where we are,

Lost in a haunted wood,

Children afraid of the night Who have never been happy or good.

Or if you think this is too much New York, too American, then how about this couplet from "The Shield of Achilles," which, to me at least, sounds a bit like a Dantesque epitaph to a handful of East European nations:

... they lost their pride

And died as men before their bodies died.

Or if you are still against such a barbarity, if you want to spare the tender skin this hurt, there are seven other lines in the same poem that should be carved on the

gates of every existing state, indeed on the gates of our whole world:

A ragged urchin, aimless and alone,

Loitered about that vacancy; a bird Flew up to safety from his well-aimed stone:

That girls are raped, that two boys knife a third, Were axioms to him, who'd never heard Of any world where promises were kept,

Or one could weep because another wept.

This way the new arrival won't be deceived as to this world's nature; this way the world's dweller won't take demagogues for demigods.

One doesn't have to be a gypsy or a Lombroso to believe in the relation between an individual's appearance and his deeds: this is what our sense of beauty is based on, after all. Yet how should a poet look who wrote:

Altogether elsewhere, vast Herds of reindeer move across Miles and miles of golden moss,

Silently and very fast.

How should a man look who was as fond of translating metaphysical verities into the pedestrian of common sense as of spotting the former in the latter? How should one look who, by going very thoroughly about creation, tells you more about the Creator than any impertinent agonist shortcutting through the spheres? Shouldn't a sensibility unique in its combination of honesty, clinical detachment, and controlled lyricism result if not in a unique arrangement of facial features then at least in a specific, uncommon expression? And could such features or such expression be captured by a brush? Registered by a camera?

I liked the process of extrapolating from that stampsize picture very much. One always gropes for a face, one always wants an ideal to materialize, and Auden was very close at the time to amounting to an ideal. (Two others were Beckett and Frost, yet I knew the way they looked; however terrifying, the correspondence between their facades and their deeds was obvious.) Sooner or later, of course, I saw other photographs of Auden: in a smuggled magazine or in other anthologies. Still they added nothing; the man eluded lenses, or they lagged behind the man. I began to wonder whether one form of art was capable of depicting another, whether the visual could apprehend the semantic.

Then one day—I think it was in the winter of 1968 or 1969—in Moscow, Nadezhda Mandelstam, whom I was visiting there, handed me yet another anthology of modern poetry, a very handsome book generously illustrated with large black-and-white photographs done by, if I remember correctly, Rollie McKenna. I found what I was looking for. A couple of months later, somebody borrowed that book from me and I never saw the photograph again; still, I remember it rather clearly.

The picture was taken somewhere in New York, it seemed, on some overpass—either the one near Grand Central or the one at Columbia University that spans Amsterdam Avenue. Auden stood there looking as though he were caught unawares, in passage, eyebrows lifted in bewilderment. The eyes themselves, however, were terribly calm and keen. The time was, presumably, the late '40s or the beginning of the '50s, before the famous wrinkled—"unkempt bed"—stage took over his features. Everything, or almost everything, became clear to me.

The contrast or, better still, the degree of disparity between those eyebrows risen in formal bewilderment and the keenness of his gaze, to my mind, directly corresponded to the formal aspects of his lines (two lifted eyebrows = two rhymes) and to the blinding precision of their content. What stared at me from the page was the facial equivalent of a couplet, of truth that's better known by heart. The features were regular, even plain. There was nothing specifically poetic about this face, nothing Byronic, demonic, ironic, hawkish, aquiline, romantic, wounded, etc. Rather, it was the face of a physician who is interested in your story though he knows you are ill. A face well prepared for everything, a sum total of a face.

It was a result. Its blank stare was a direct product of that blinding proximity of face to object which produced expressions like "not an important failure," "necessary murder," "conservative dark," "apathetic grave," or "well-run desert." It felt like when a myopic person takes off his glasses, except that the keensightedness of this pair of eyes had to do with neither myopia nor the smallness of objects but with their deep-seated threats. It was the stare of a man who knew that he wouldn't be able to weed those threats out, yet who was bent on describing for you the symptoms as well as the malaise itself. That wasn't what's called "social criticism"—if only because the malaise wasn't social: it was existential.

In general, I think this man was terribly mistaken for a social commentator, or a diagnostician, or some such thing. The most frequent charge that's been leveled against him was that he didn't offer a cure. I guess in a way he asked for that by resorting to Freudian, then Marxist, then ecclesiastical terminology. The cure, though, lay precisely in his employing these terminologies, for they are simply different dialects in which one can speak about one and the same thing, which is love. It is the intonation with which one talks to the sick that cures. This poet went about the world's grave, often terminal cases not as a surgeon but as a nurse, and every patient knows that it's nurses and not incisions that eventually put one back on one's feet. It's the voice of a nurse, that is, of love, that one hears in the final speech of Alonso to Ferdinand in "The Sea and the Mirror":

But should you fail to keep your kingdom

And, like your father before you, come

Where thought accuses and feeling mocks,

Believe your pain...

Neither physician nor angel, nor—least of all—your beloved or relative will say this at the moment of your final defeat: only a nurse or a poet, out of experience as well as out of love.

And I marveled at that love. I knew nothing about Auden's life: neither about his being homosexual, nor about his marriage of convenience (for her) to Erika Mann, etc.—nothing. One thing I sensed quite clearly was that this love would overshoot its object. In my mind—better, in my imagination—it was love expand-

ed or accelerated by language, by the necessity of expressing it; and language—that much I already knew—has its own dynamics and is prone, especially in poetry, to use its self-generating devices: meters and stanzas that take the poet far beyond his original destination. And the other truth about love in poetry that one gleans from reading it is that a writer's sentiments inevitably subordinate themselves to the linear and unrecoiling progression of art. This sort of thing secures, in art, a higher degree of lyricism; in life, an equivalent in isolation. If only because of his stylistic versatility, this man should have known an uncommon degree of despair, as many of his most delightful, most mesmerizing lyrics do demonstrate. For in art lightness of touch more often than not comes from the very darkness of its absence.

And yet it was love all the same, perpetuated by language, oblivious—because the language was English—to gender, furthered by the deepest agony, because agony, in the end, would have to be articulated. Language, after all, is self-conscious by definition, and it wants to get the hang of every new situation. As I looked at Rollie McKenna's picture, I felt pleased that the face there revealed neither neurotic nor any other sort of strain, that it was pale, ordinary, not expressing but instead absorbing whatever it was that was going on in front of his eyes. How marvelous it would be, I thought, to have those features, and I tried to ape the grimace in the mirror. I obviously failed, but I knew that I would fail, because such a face was bound to be one of a kind. There was no need to imitate it: it already existed in the world, and the world seemed somehow more palatable to me because this face was somewhere out there.

Strange things they are, faces of poets. In theory, authors' looks should be of no consequence to their readers: reading is not a narcissistic activity, neither is writing, yet the moment one likes a sufficient amount of a poet's verse one starts to wonder about the appearance of the writer. This, presumably, has to do with one's suspicion that to like a work of art is to recognize the truth, or the degree of it, that art expresses. Insecure by nature, we want to see the artist, whom we identify with his work, so that the next time around we might know what truth looks like in reality. Only the authors of antiquity escape this scrutiny, which is why, in part, they are regarded as classics, and their generalized marble features that dot niches in libraries are in direct relation to the absolute archetypal significance of their oeuvre. But when you read

... 7o visit

The grave of a friend, to make an ugly scene,

To count the loves one has grown out of,

Is not nice, but to chirp like a tearless bird,

As though no one dies in particular

And gossip were never true, unthinkable. .. you begin to feel that behind these lines there stands not a blond, brunette, pale, swarthy, wrinkled, or smooth-faced concrete author but life itself; and that you would like to meet; that you would like to find yourself in human proximity to. Behind this wish lies not vanity but certain human physics that pull a small particle toward a big magnet, even though you may end up by echoing Auden's own: "I have known three great poets, each one a prize son of a bitch." I: Who? He: "Yeats, Frost, Bert Brecht." (Now about Brecht he was wrong: Brecht wasn't a great poet.)

A PASSION OF POETS

On June 6, 1972, some forty-eight hours after I had left Russia on very short notice, I stood with my friend Carl Proffer, a professor of Russian literature at the University of Michigan (who'd flown to Vienna to meet me), in front of Auden's summer house in the small village of Kirchstetten, explaining to its owner the reasons for our being there. This meeting almost didn't happen.

There are three Kirchstettens in northern Austria, and we had passed through all three and were about to turn back when the car rolled into a quiet, narrow country lane and we saw a wooden arrow saying "Audenstrasse." It was called previously (if I remember accurately) "Hinterholz" because behind the woods the lane led to the local cemetery. Renaming it had presumably as much to do with the villagers' readiness to get rid of this "memento mori" as with their respect for the great poet living in their midst. The poet regarded the situation with a mixture of pride and embarrassment. He had a clearer sentiment, though, toward the local priest, whose name was Schickelgruber: Auden couldn't resist the pleasure of addressing him as "Father Schicklgruber."

All that I would learn later. Meanwhile, Carl Proffer was trying to explain the reasons for our being here to a stocky, heavily perspiring man in a red shirt and broad suspenders, jacket over his arm, a pile of books underneath it. The man had just come by train from Vienna and, having climbed the hill, was short of breath and not disposed to conversation. We were about to give up when he suddenly grasped what Carl Proffer was saying, cried "Impossible!" and invited us into the house. It was Wystan Auden, and it was less than two years before he died.

Let me attempt to clarify how all this had come about. Back in 1969, George L. Kline, a professor of philosophy at Bryn Mawr, had visited me in Leningrad. Professor Kline was translating my poems into English for the Penguin edition and, as we were going over the content of the future book, he asked me whom I would ideally prefer to write the introduction. I suggested Auden—because England and Auden were then synonymous in my mind. But, then, the whole prospect of my book being published in England was quite unreal. The only thing that imparted a semblance of reality to this venture was its sheer illegality under Soviet law.

All the same, things were set in motion. Auden was given the manuscript to read and liked it enough to write an introduction. So when I reached Vienna, I was carrying with me Auden's address in Kirchstetten. Looking back and thinking about the conversations we had during the subsequent three weeks in Austria and later in London, I hear more his voice than mine, although, I must say, I grilled him quite extensively on

the subject of contemporary poetry, especially about the poets themselves. Still, this was quite understandable because the only English phrase I knew I wasn't making a mistake in was "Mr. Auden, what do you think about..."—and the name would follow.

Perhaps it was just as well, for what could I tell him that he didn't already know one way or another? I could have told him, of course, how I had translated several poems of his into Russian and took them to a magazine in Moscow; but the year happened to be 1968, the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia, and one night the BBC broadcast his "The Ogre does what ogres can..." and that was the end of this venture. (The story would perhaps have endeared me to him, but I didn't have a very high opinion of those translations anyway.) That I'd never read a successful translation of his work into any language I had some idea of? He knew that himself, perhaps all too well. That I was overjoyed to learn one day about his devotion to the Kierkegaardian triad, which for many of us too was the key to the human species? But I worried I wouldn't be able to articulate it.

It was better to listen. Because I was Russian, he'd go on about Russian writers. "I wouldn't like to live with Dostoyevsky under the same roof," he would declare. Or, "The best Russian writer is Chekhov"— "Why?" "He's the only one of your people who's got common sense." Or he would ask about the matter that seemed to perplex him most about my homeland: "I was told that the Russians always steal windshield wipers from parked cars. Why?" But my answer—because there were no spare parts—wouldn't satisfy him: he obviously had in mind a more inscrutable reason, and, having read him, I almost began to see one myself. Then he offered to translate some of my poems. This shook me considerably. Who was I to be translated by Auden? I knew that because of his translations some of my compatriots had profited more than their lines deserved; yet somehow I couldn't allow myself the thought of him working for me. So I said, "Mr. Auden, what do you think about.. .Robert Lowell?" "I don't like men," came the answer, "who leave behind them a smoking trail of weeping women."

During those weeks in Austria he looked after my affairs with the diligence of a good mother hen. To begin with, telegrams and other mail inexplicably began to arrive for me "c/o W. H. Auden." Then he wrote to the Academy of American Poets requesting that they provide me with some financial support. This was how I got my first American money—$1,000 to be precise—and it lasted me all the way to my first payday at the University of Michigan. He'd recommend me to his agent, instruct me on whom to meet and whom to avoid, introduce me to friends, shield me from journalists, and speak ruefully about having given up his flat on St. Mark's Place—as though I were planning to settle in his New York. "It would be good for you. If only because there is an Armenian church nearby, and the Mass is better when you don't understand the words. You don't know Armenian, do you?" I didn't.

Then from London came—c/o W. H. Auden—an invitation for me to participate in the Poetry International in Queen Elizabeth Hall, and we booked the same flight by British European Airways. At this point an opportunity arose for me to pay him back a little in kind. It so happened that during my stay in Vienna I had been befriended by the Razumovsky family (descendants of the Count Razumovsky of Beethoven's Quartets). One member of that family, Olga Razumovsky, was working then for the Austrian Airlines. Having learned about W. H. Auden and myself taking the same flight to London, she called BEA and suggested they give these two passengers the royal treatment. Which we indeed received. Auden was pleased, and I was proud.

On several occasions during that time, he urged me to call him by his Christian name. Naturally I resisted—and not only because of how I felt about him as a poet but also because of the difference in our ages: Russians are terribly mindful of such things. Finally in London he said, "It won't do. Either you are going to call me Wystan, or I'll have to address you as Mr. Brodsky." This prospect sounded so grotesque to me that I gave up. "Yes, Wystan," I said. "Anything you say, Wystan." Afterward we went to the reading. He leaned on the lectern, and for a good half an hour he filled the room with the lines he knew by heart. If I ever wished for time to stop, it was then, inside that large dark room on the south bank of the Thames. Unfortunately, it didn't. Although a year later, three months before he died in an Austrian hotel, we did read together again. In the same room.

By that time he was almost sixty-six. "I had to move to Oxford. I am in good health, but I have to have somebody to look after me." As far as I could see, visiting him there in January 1973, he was looked after only by the four walls of the sixteenth-century cottage given him by the college, and by the maid. In the dining hall the members of the faculty jostled him away from the food board. I supposed that was just English school manners, boys being boys. Looking at them, however, I couldn't help recalling one more of those blinding approximations of Wystan's: "triviality of the sand."

This foolery was simply a variation on the theme of society having no obligation to a poet, especially to an old poet. That is, society would listen to a politician of comparable age, or even older, but not to a poet. There are a variety of reasons for this, ranging from anthropologic ones to the sycophantic. But the conclusion is plain and unavoidable: society has no right to complain if a politician does it in. For, as Auden once put it in his "Rimbaud,"

But in that child the rhetorician's lie

Burst like a pipe: the cold had made a poet.

If the lie explodes this way in "that child," what happens to it in the old man who feels the cold more acutely? Presumptuous as it may sound coming from a foreigner, the tragic achievement of Auden as a poet was precisely that he had dehydrated his verse of any sort of deception, be it a rhetorician's or a bardic one. This sort of thing alienates one not only from faculty members but also from one's fellows in the field, for in every one of us sits that red-pimpled youth thirsting for the incoherence of elevation.

Turning critic, this apotheosis of pimples would regard the absence of elevation as slackness, sloppiness, chatter, decay. It wouldn't occur to his sort that an aging poet has the right to write worse—if indeed he does—that there's nothing less palatable than unbecoming old age "discovering love" and monkey-gland transplants. Between boisterous and wise, the public will always choose the former (and not because such a choice reflects its demographic makeup or because of poets' own "romantic" habit of dying young, but because of the species' innate unwillingness to think about old age, let alone its consequences). The sad thing about this clinging to immaturity is that the condition itself is far from being permanent. Ah, if it only were! Then everything could be explained by the species' fear of death. Then all those "Selected Poems" of so many a poet would be as innocuous as the citizens of Kirchstetten rechristening their "Hinterholz." If it were only fear of death, readers and the appreciative critics especially should have been doing away with themselves nonstop, following the example of their beloved young authors. But that doesn't happen.

The real story behind our species' clinging to immaturity is much sadder. It has to do not with man's reluctance to know about death but with his not wanting to hear about life. Yet innocence is the last thing that can be sustained naturally. That's why poets—especially those who lasted long—must be read in their entirety,, not in selections. The beginning makes sense only insofar as there is an end. For unlike fiction writers, poets tell us the whole story: not only in terms of their actual experiences and sentiments but—and that's what's most pertinent to us—in terms of language itself, in terms of the words they finally choose.

An aging man, if he still holds a pen, has a choice: to write memoirs or to keep a diary. By the very nature of their craft, poets are diarists. Often against their own will, they keep the most honest track of what's happening (a) to their souls, be it the expansion of a soul or—more frequently—its shrinkage, and (b) to their sense of language, for they are the first ones for whom words become compromised or devalued. Whether we like it or not, we are here to learn not just what time does to man but what language does to time. And poets, let us not forget, are the ones "by whom it [language] lives." It is this law that teaches a poet a greater rectitude than any creed is capable of.

That's why one can build a lot upon W. H. Auden. Not only because he died at twice the age of Christ or because of Kierkegaard's "principle of repetition." He simply served an infinity greater than we normally reckon with, and he bears good witness to its availability; what's more, he made it feel hospitable. To say the least, every individual ought to know at least one poet from cover to cover: if not as a guide through the world, then as a yardstick for the language. W. H. Auden would do very well on both counts, if only because of their respective resemblances to Hell and Limbo.

He was a great poet (the only thing that's wrong with this sentence is its tense, as the nature of language puts one's achievements within it invariably into the present), and I consider myself immensely lucky to have met him. But had I not met him at all, there would still be the reality of his work. One should feel grateful to fate for having been exposed to this reality, for the lavishing of these gifts, all the more priceless since they were not designated for anybody in particular. One may call this a generosity of the spirit, except that the spirit needs a man to refract itself through. It's not the man who becomes sacred because of this refraction: it's the spirit that becomes human and comprehensible. This—and the fact that men are finite—is enough for one to worship this poet.

A PASSION OF POETS

Whatever the reasons for which he crossed the Atlantic and became American, the result was that he fused both idioms of English and became—to paraphrase one of his own lines—our transatlantic Horace. One way or another, all the journeys he took—through

lands, caves of the psyche, doctrines, creeds—served not so much to improve his argument as to expand his diction. If poetry ever was for him a matter of ambition, he lived long enough for it to become simply a means of existence. Hence his autonomy, sanity, equipoise, irony, detachment—in short, wisdom. Whatever it is, reading him is one of the very few ways (if not the only one) available for feeling decent. I wonder, though, if that was his purpose.

I saw him last in July 1973, at a supper at Stephen Spender's place in London. Wystan was sitting there at the table, a cigarette in his right hand, a goblet in his left, holding forth on the subject of cold salmon. The chair being too low, two disheveled volumes of the OED were put under him by the mistress of the house. I thought then that I was seeing the only man who had the right to use those volumes as his seat. Q

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now