Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBeating the Devil John Huston

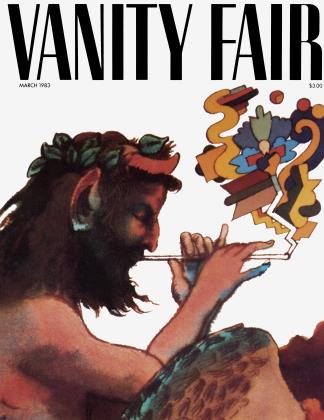

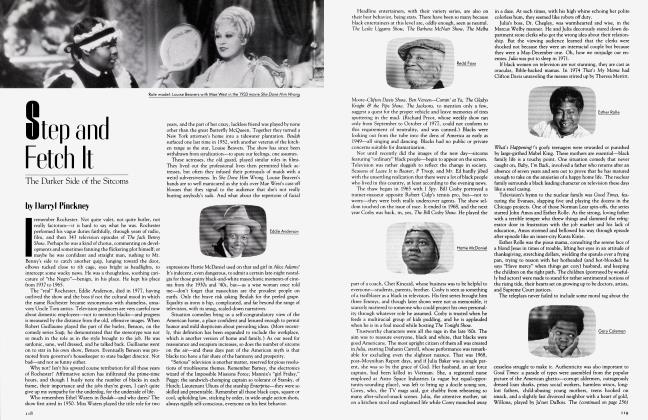

He could pass for Saint Nick or Old Scratch, depending on how the light hits him, and that's a disturbing quality in a movie villain. Huston makes a great one—the leathery grin and the imp's twinkle don't quite conceal a certain leonine savagery. And the voice: plangent, luxurious. It's such a plush, deep-pile purr that one feels vaguely decadent just listening to it.

For forty-two years he has directed adventure movies, quests for dominion or gold in which the dominion collapses and the gold blows away in the wind. Huston's wisdom is ancient but not obscure: for him, it's never the destination that counts, but the journey. Humphrey Bogart called him the Monster, and he soon began signing his correspondence that way. The correspondence came from great distances: from Africa, where he filmed The African Queen, The Roots of Heaven, and The Man Who Would Be King, or from Puerto Vallarta, where he shot The Night of the Iguana and where he now makes his home.

We imagine him to be the quintessential American director, but in fact his passport is Irish—a good passport to have if you're a gambler who might come up short around tax time. The gambling, the hunting, the practical jokes, the succession of wives (five, if we haven't lost count), the platoon of rotten movies that troop in lockstep with the masterpieces—all this has given him the air of a shaggy dilettante, more intrigued with the adventures he can have on a ramshackle movie set in an exotic clime than with the resultant frenzy on the screen.

His critical reputation has suffered as a result. He's a macho blowhard, auteurists have claimed, and he has no style. But style is precisely his bailiwick; it's the pretext for the life and the subject of the movies. His men and women tell us who they are by the way they smoke their cigarettes or grip their revolvers. They live by ornate codes of friendship and grace under pressure, and they recognize a peer by the eloquence of his style.

Look at the face, the white beard that echoes the shock of hair. He's a Hemingway tough guy, a trench-coat existentialist. His style hankers after Papa's. And still he works, the grand old reprobate, occasionally conjuring wonders like The Man Who Would Be King and Wise Blood; in between, there are the tossed-off bagatelles that keep him in poker money. His most recent film was a ticking mechanical doll called Annie; the one before that a honking horror called Phobia. Within this craggy leprechaun, this Monster in winter, the struggle between Saint Nick and Old Scratch never abates.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now