Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFalling in Style

The New Art and Our Discontents

Peter Schjeldahl

In art, it's one of those moments when everybody interesting seems to be twenty-nine years old. It is a boom time in terms of energy, sensation, and—despite frequent, almost eager predictions of market collapse—money and the kind of curiosity money excites. A new generation is on the rise internationally, its sensibilities abrasive and strange but unusually communicative. Most of the values that the twentieth century has thought it found in art, from the quasi-religious to the definitely chic, are active and crowding together, like so much fissionable material on its way to critical mass. Nothing comparable has happened since the pop, minimal, and post-abstract-expressionist '60s, when contemporary art was first geared into the media machine. How that moment waned—or how a fashionable interest in art was deflected by the institutionalization of the avantgarde—is a story to be told. How art regained urgency and direct dazzle is a story we are living now.

Who are "we"? We are "the public" following exhibitions and the art press or merely knitting brows over the latest celebrity treatment of a hot young artist or dealer. Visual art is still mainly an affair of objects handmade in solitude, then negotiated and validated in virtual secrecy. Art thus has a public only long after the fact, less a public at all than a band of villagers receiving mysterious messages from the castle on the hill. But what if visual art were to open up its modes of address, assimilating messages from the village and beaming back responses? Then the "we" of a public responding vicariously might resolve into active "I"s, into individuals with firsthand uses for art. Such is the dream of what is "new" in art and art criticism now.

Twenty years ago, the success of contemporary art in America inflicted a long-term trauma on artists. If American art created heroes in the '50s, stars in the '60s, and in the '70s produced hits, the transition from heroes to stars was the cruncher: a viciously ironic fulfillment of the abstract expressionists' ambition to Americanize modernism. This posed no problem for Andy Warhol, whom the angels made in heaven for that moment, but practically everyone else was spurred to resistance or evasive action.

Some artists got around the crisis by retreating, or ascending, into a glamorous professionalism. "Content" became a gaucherie for such tough-minded aesthetic pragmatists as Frank Stella, Donald Judd, and Roy Lichtenstein—major artists of an unprecedented kind—and as a critical category content was vaporized into genteel haze by those who took Clement Greenberg's formalist line. Hard-core minimalists were grittier, mounting a "dialectical" attack on art's new commodity status. Like the pictorial Vista Vision of Stella and the formalists, the sculpture of Carl Andre and Richard Serra defied media reproduction; further, it functioned strictly by inducing self-consciousness in its viewers. Then came conceptualism—minimalism minus objects. It gave the dialectical screw the final turn, which broke it. (Some artists of rigorous but less rigid mind, notably Jasper Johns and Robert Smithson, achieved complexities that outsmart any reduction, and these artists are still at issue as their contemporaries are not.)

The irony that fate cooked up for minimalism, which had declared war on art's conventional confinements, was wholesale institutionalization—in museums, universities, "site-specific" outdoor shows, public commissions, and "alternative spaces." The famous pluralism of art in the '70s was a bureaucratic convenience, a system of care and feeding, largely with public funds, for the now completely toothless tigers of the avant-garde. Pluralist attention was rarely lavished on, say, traditional realism, unless the artist was a woman. (Feminist politics had the last word in the art world of the '70s.) This was the era of the art expert: commissioner, curator, corporate consultant, fund raiser, freelance critic. Support structures flourished while art puttered. The hits of the decade—decoration, performance, photo-realism—were like firecrackers going off in sludge. But accounts of the avant-garde's death in a smother of acceptance were premature.

The avant-garde is not defined by a particular community or ideology. It is an intermittent expression of galvanized dissatisfaction, and as the '70s plugged along there was plenty to be dissatisfied about. Young artists raised on the media glut and a thousand art-historical slide lectures were cool to both modernist myths and the lure of the new institutional havens and career tracks. They didn't reject their precursors because they didn't reject anything. But they started doing things they weren't supposed to do—drawing and painting recognizable images, cultivating unruly emotions, and honing the cold steel of ironies that cut more ways than one. Among other things, they shrugged off the ritual anticommercialism that had helped to back serious art into an institutional and academic cul-de-sac, and had had roughly the impact on capitalism of a beanbag hurled against cement. Ambition to make a difference in art and, through art, in the world proved more compelling than disgust with the commodity culture, and the political passions that had engulfed the art world around 1970 were being resublimated a few years later.

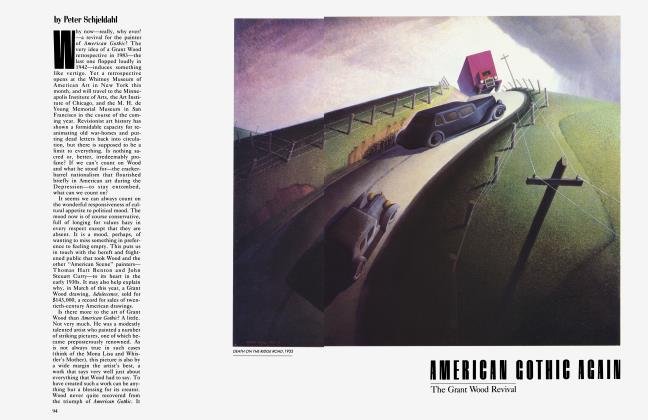

In retrospect, certain hits and curiosities of the '70s loom prophetically. Already, in the late '60s, there had been the considerable scandal of Philip Guston's abandonment of sensitive abstraction for anguished, cartoony images. Malcolm Morley, with expressionistically rendered toys and animals, later followed Guston down the road to what seemed terminal eccentricity.

Neil Jenney's amazingly simpleminded images, in what looked like finger paintings, kept popping up in group shows and gallery back rooms, a bit less dismissable each time. William Wegman's deliberately silly photos of a dog named Man Ray were also inexplicably gripping. And I remember my befuddlement when, in 1974, I saw some large paintings that were formally flat and gridbased in the conventional way of abstraction then but happened to contain the unmistakable contours of horses. It had to be a joke, but it didn't feel like a joke. The paintings were grander and stronger than any new abstraction I had seen in years. I had never heard of the artist: Susan Rothenberg.

A "return of the repressed" seemed in progress—a rush of energy and a hunger for images, long high-hatted in New York as the sort of thing one associated with regional centers like Chicago and the Bay Area. It was coming, furthermore, from some very sophisticated youngsters. Other painters besides Rothenberg were combining loaded images with well-schooled big-painting aesthetics.

The minimalist-installational savvy of Jonathan Borofsky little prepared viewers for the childish obsessions and dreams he unclenched in his memorably unnerving shows during the late '70s. Similarly, painters and photographic artists like David Salle, Robert Longo, and Cindy Sherman were using media-related images in ways plainly influenced by conceptualism, but with a difference.

They had the feel of fire and ice, of emotional ferocity locked in gelid presentations, that seemed to come out of nowhere. It being axiomatic that nothing interesting happened in Europe, few were aware that parallel developments were already well along in Germany and Italy. But something big was obviously afoot, which some wrongly called a regression and some wrongly called a new departure. In reality, it was a sea change.

Or, to put it another way, the '70s provided a quiet laboratory for art, where a little of this was serendipitously added to a little of that until, one day, the mixture exploded.

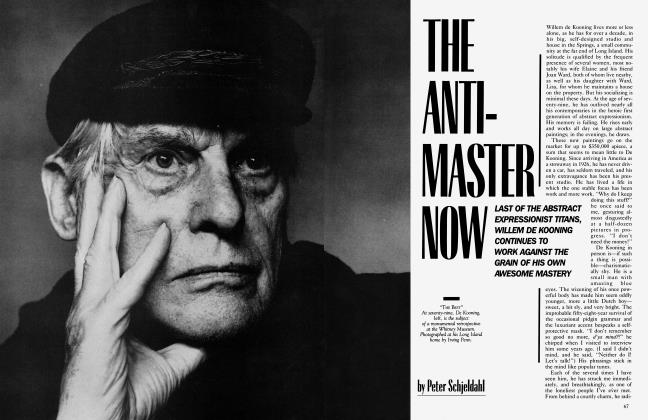

For the art world, the eureka moment was marked by the simultaneous appearance in 1979 of painter Julian Schnabel and his dealer, Mary Boone. Both were and are brash, panting for glory, and without an ounce of diffidence between them. Schnabel, who at thirty-one is still the most controversial artist in the known universe, had crammed his extraordinarily retentive brain and arm with a host of artistic models, including several new European ones (notably Joseph Beuys, Sigmar Polke, and Anselm Kiefer). He proceeded to disgorge this stylistic Ur-stuff all at once—in huge, tremendously pretentious, very exciting paintings of operatically romantic images on broken china, velvet, animal skins, rugs, and tarpaulin, with deer antlers attached and titles like St. Francis in Ecstasy and Portrait of God. The contrast to the tentative gestures that passed for originality in the '70s was dramatic, to say the least. Schnabel put Boone on the map, and, with the invaluable collaboration of dealer Leo Castelli, she made the most of it. For better or worse, art suddenly had a public again.

To understand the Schnabel phenomenon, it is crucial to see the value of his shamelessness. One reason the lull of the '70s lasted so long was the sheer intimidation of the young by the truculent morality of their role models, a morality all the fiercer for its evasion of the crisis brought on by art's worldly success. "Seriousness" in the '70s was monastic. If art was again to be exuberantly serious and seriously exuberant, the hollowness of the old strictures had to be noted. But for sensitive students, the collapse of the old ideals was an intense humiliation—like the nakedness of one's father—that few could face. (Is there a connection between the humiliation of American modernism after the '60s and that of American power after Vietnam— and, for good measure, that of the New Left after 1968? I don't know.) Like Warhol and Salvador Dali before him, Schnabel appears not to have an embarrassable bone in his body. This plus talent and timing made for one of the luckiest hands an ambitious artist was ever dealt.

So through the breach made by Schnabel's broad shoulders has come the torrent. It has deluged the galleries, though not, for the most part, our museums. Collectors and dealers, not critics and curators, are sorting out reputations these days, giving rise to cynical suspicions of a market cabal. (The byzantine art world, like the CIA, is always presumed guilty.) But, in reality, the new art is spontaneous and very broadly based. The dozen or so New York dealers who represent the twenty or thirty hottest new artists are more or less agilely riding the wave, not generating it. If this were a market scheme, it would be a sorry one, having failed to meet the first requirement of sound marketing: a trade name. Labels keep being slapped on the new art and keep falling off: "new image," "new wave," "neo-expressionism," "bad painting, " "pictures, " "illustration and allegory," "new figuration," "naive nouveau," "transavant-garde" (from Italy), "wild painters" (Germany), "free figuration" (France), and special senses of that rhetorical chameleon "postmodernism," all have had their day. But then, how does one set about packaging a spirit that manages to embrace the somber nature abstractions of the Dane Per Kirkeby and the scraggly effusions of moonlighting punk performers and graffiti kids?

It cannot be said too strongly that much if not most of the best new art is being made in Europe, where American art people can increasingly be seen roaming in jet-lagged stupors through the big omnibus shows that Europeans put together so well and so often. U.S. museums, slow enough to pick up on native developments, are acting as if the news from abroad were addressed to someone else. Hardly anyone, really, seems intellectually or emotionally equipped to cope with the enormous expansion of art's worldly connections and frames of reference. We may be seeing the global village come true—not the rosy dream of technological utopia left over from the '60s but a thorny reality being registered in the antique mediums of paint and canvas and in styles superficially old-fashioned.

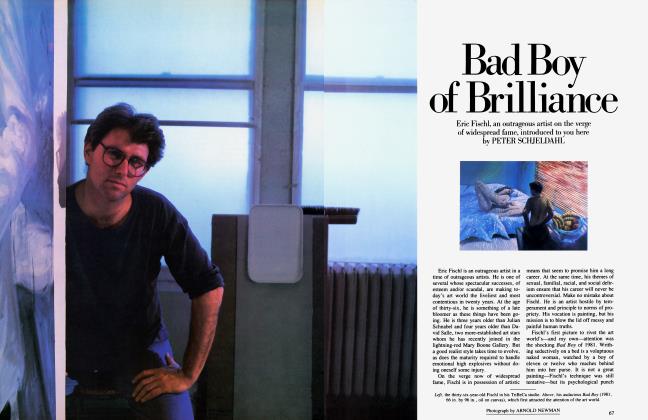

David Salle, Cindy Sherman, and Eric Fischl are three young New York artists who are excellent in themselves and paradigmatic of the new art. Salle is often mentioned in the same breath with Schnabel—both are represented by Mary Boone and have received the consecration of simultaneous shows in her gallery and in Leo Castelli's. When people grumble about art-world hype, they are grumbling about Salle as much as Schnabel—even most of all about Salle, whose cool blatancy, without the fetching geewhiz panache of his colleague, strikes many as the very image of art in an age of mass marketing. Salle, as it happens, might be inclined to agree and even to take the implied criticism several steps further, in a kind of infinite regress of self-consuming anxiety and doubt. That he does so in paintings that are racily beautiful and desirable, once you get the hang of them, is simply part of an ironic spiral: his simultaneous acceptance and mockery of all that art is used for, from spiritual uplift to over-the-couch decor. Salle pushes a play of images and their meanings to a point where selfcanceling incoherence seems a given, then he ups the ante some more.

Salle uses images and painting devices taken from sources far and near, high and low, popular and arcane, from life-drawing classes and history books and pornographic magazines. Nothing in his work is not a pre-existing image, and even the aesthetic model is borrowed: the New York school "big painting" in his hands becomes as self-conscious as a debutante in squeaky shoes. But the calculation involved is not so arch as it looks. Salle's coldness is the cumulative effect of a tension or standoff among conflicting emotions. Emotions strong in intensity but weak in kind—sentimentality, hostility, guilt, bewilderment—are impacted into a working model of consciousness under stress. Why do I find this thrilling? Maybe because Salle, like Godard and Fassbinder in their films, discovers a possibility of poise and even ebullience in the debased language of the medium. Salle has remarked that artists today are like politicians—meaning, perhaps, that (apart from the obvious fact that a lot of them seem to be running for something) they identify and orchestrate the discontents of the people. The stage of historic action is beyond the reach of mere art, but today mere artists are demonstrating that, just as mass images oppress us, a "politically" focused game of images may be a wedge of liberation.

(continued on page 252)

Continued from page 116

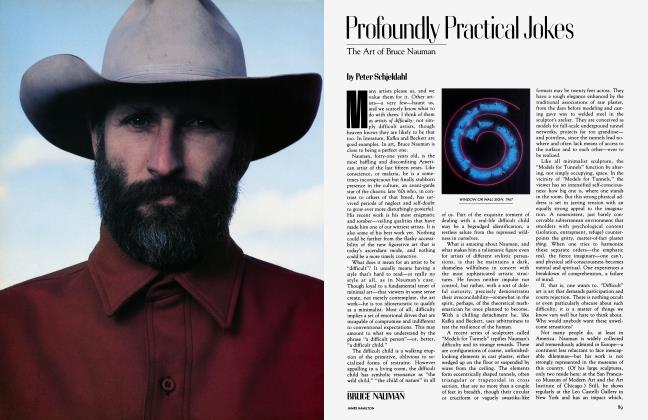

No one, including Salle, is playing a game more focused and intimately liberating than Cindy Sherman. Sherman's large photographs of herself in the invented or movie-inspired roles of variously troubled women (and lately of men) have roots in '70s feminism, autobiography, and performance art—elements that have often been combined by others, but never with such flair and force. She began with intoxicating evocations of film noir—a busty librarian, a hitchhiking teen—and worked her way through identifications with introverted, ravaged characters of a kind played by, for instance, Monica Vitti. She has since progressively eliminated narrative and movie references while sharpening her formidable technique. The result is a synthesis of acting, directing, lighting, costuming, makeup, and processing (all done by herself) as pure as the flame of a blowtorch. Her subject is the contingent fiction—the hope and the defeat—of selfhood. She takes the narcissistic "camp" sensibility to a harrowing extreme of deadearnestness. Each of her pictures poses an ultimate question to the self: Who are you? What are you? Are you?

If Salle makes a fiesta of glut and confusion, Sherman makes an almost religious rite of blankness and anomie. Without succumbing to exhibitionism or voyeurism, she uses herself to pursue subjectivity through a maze of its guises—dead ends in which the self risks getting lost. This sounds metaphysical, but the effect of confronting a Sherman photo on the wall is anything but abstract. Salle inventories consciousness; Sherman presents consciousness in hardened chunks.

The vulnerability, the nakedness, of Sherman's self-portraits is not hers alone. It is impossible to know—and immaterial—who Cindy Sherman is. This politics of acknowledging common terror gives her work lift-off, affirming even as it exposes. Precisely here, her pictures seem to say, in degradation and disorientation, our reality begins.

Fischl's art appears to be and in many ways truly is conventional; its painterly aesthetic, though at times giving off a faint whiff of Edvard Munch, has more in common with the serviceable modes of Edward Hopper and Reginald Marsh. For this very reason, the peculiar "shock of the new" in his work clinchingly demonstrates contemporary art's altered state. Fischl's theme is the psychological trauma that from childhood imposes a lasting stutter of incapacity between the self and others, even between the self and its own desires. Fischl, using the most standard and therefore reassuring pictorial instruments, burrows beneath consciousness to those knots of past experience that are all beginning and middle with no end, no resolution, moments when one almost dispassionately watches an approaching reality, like an onrushing truck, and cannot budge an inch to get out of the way.

The main class of trauma Fischl confronts is erotic. The riveting, frightening nakedness of adults as perceived by children is the subject to which he returns as the tongue returns to a cavity. The autobiographical element in Fischl's work, as in Sherman's, is finally irrelevant. The symbolic truth of his pictures resonates far beyond nude beaches and incestuous seductions—recurrent motifs in his work— tq an underlying reef of psychic injuries. The .catastrophic failure of modern society to provide secure structures for human development has long been decried by psychologists and sociologists. A good Fischl painting is worth a mountain of studies that lend themselves so readily to intellectual and moralistic evasions. Like the traumas they rehearse, his pictures burn themselves into the mind.

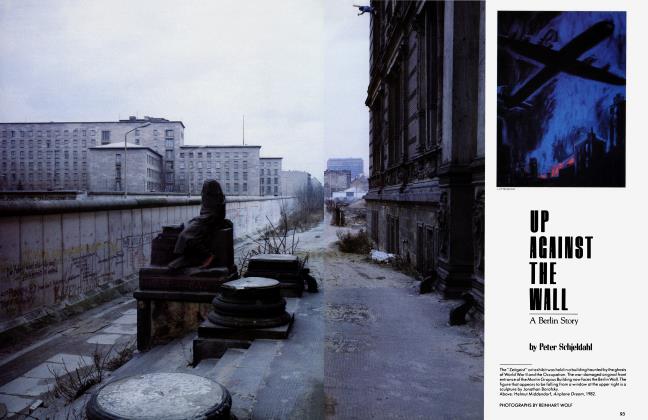

Compared with Schnabel, Salle, Sherman, and Fischl—and maybe Robert Longo, about whose images of worst-case urban violence I remain undecided—most claimants to newness in American art are either less ambitious in reach or less sure in grasp. But many are finding strongly individual uses for widely shared ideas and energies. David Amico, Auste, Jean Michel Basquiat, Richard Bosman, David Deutsch, Jedd Garet, Roberto Juarez, Judy Rifka, and Frank Young are painters making distinctive contributions to an ever-growing array of edgy expressionistic styles. Painters and photographic and "verbal" artists, including Mike Glier, Jack Goldstein, Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, Thomas Lawson, Sherrie Levine, Matt Mullican, Richard Prince, and Walter Robinson, are rapidly developing their rangy, biting critiques of the "languages" of mass politics and aesthetics. (Sculpture, the most significant mode of the '70s, plays no important role in the new art—with the main exception of John Ahearn's painted life casts of the South Bronx poor.) Then there is the demotic street-kid scene, whose star is Keith Haring, a cartoon cowboy making it big in the galleries while still inflicting lovely vandalism on the New York subways. Inevitably, new sensibilities entail reassessment of old, often neglected styles and reputations. Leon Golub, sixty-one, comes to mind: his recent, masterly, harrowing paintings of political violence in the third world are as up-to-the-minute in every important way as anything by any Zeitgeist-drunk twenty-nine-year-old.

The new art descends to all levels of giddiness and pain, of mania and depression. At each level, snarls of repressed energy spring loose. This won't be the first time a dark day for the world was a good day for art—history is full of splendors framed by blood and fear—but this is surely one of the strangest, because ours is a civilization without bearings. The new art comes not to praise or to bury contradiction, but to work in and through it. Is there bedrock beneath the chaos? If not, we are witnessing the spectacle of a culture committing suicide. But if the work of these new artists is something more than a fine, doomed gesture, what has been discovered on the way down will come in handy on the way back up.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now