Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLosing the Edge

Stephen Jay Gould

I wish to propose a new kind of explanation for the oldest chestnut of the hot stove league—the most widely discussed trend in the history of baseball statistics: the extinction of the .400 hitter. Baseball aficionados wallow in statistics, a sensible obsession that outsiders grasp with difficulty and ridicule often. The reasons are not hard to fathom. In baseball, each essential action is a contest between two individuals—batter and pitcher, or batter and fielder— thus creating an arena of truly individual achievement within a team sport.

The abstraction of individual achievement in other sports makes comparatively little sense. Goals scored in basketball or yards gained in football depend on the indissoluble intricacy of team play; a home run is you against him. Moreover, baseball has been played under a set of rules and conditions sufficiently constant during our century to make comparisons meaningful, yet sufficiently different in detail to provide endless grist for debate (the "dead ball" of 1900-20 versus the "lively ball" of later years, the introduction of night games and relief pitchers, the changing and irregular sizes of ball parks, nature's own versus Astroturf).

No subject has inspired more argument than the decline and disappearance of the .400 hitter—or, more generally, the drop in league-leading batting averages during our century. Since we wallow in nostalgia and have a lugubrious tendency to compare the present unfavorably with a past "golden era," this trend acquires all the more fascination because it carries moral implications linked metaphorically with junk foods, nuclear bombs, and eroding environments as signs of the decline of Western civilization.

Between 1901 and 1930, league-leading averages of .400 or better were common enough (nine out of thirty years) and achieved by several players (Lajoie, Cobb, Jackson, Sisler, Heilmann, Hornsby, and Terry), and averages over .380 scarcely merited extended commentary. Yet the bounty dried up abruptly thereafter. In 1930 Bill Terry hit .401 to become the last .400 hitter in the National League; and Ted Williams's .406 in 1941 marked the last pinnacle for the American League. Since Williams, the greatest hitter I ever saw, attained this goal—in the year of my birth—only three men have hit higher than .380 in a single season: Williams again in 1957 (.388, at age thirty-nine, with my vote for the greatest batting accomplishment of our era), Rod Carew (.388 in 1977), and George Brett (.390 in 1980). Where have all the hitters gone?

Two kinds of explanation have been offered. The first, naive and moral, simply acknowledges with a sigh that there were giants in the earth in those days. Something in us needs to castigate the present in the light of an unrealistically rosy past. In researching the history of misconduct, I discovered that every generation (at least since the mid-nineteenth century) has imagined itself engulfed in a crime wave. Each age has also witnessed a shocking decline in sportsmanship. Similarly, senior citizens of the hot stove league, and younger fans as well (for nostalgia seems to have its greatest emotional impact on those too young to know a past reality directly), tend to argue that the .400 hitters of old simply cared more and tried harder. Well, Ty Cobb may have been a paragon of intensity and a bastard to boot, and Pete Rose may be a gentleman by comparison, but today's play is anything but lackadaisical. Say what you will, monetary rewards in the millions do inspire single-minded effort.

The second kind of explanation views people as much of a muchness over time and attributes the downward trend in league-leading batting to changes in the game and its styles of play. Most often cited are improvements in pitching and fielding, and more grueling schedules that shave off the edge of excellence.

Another explanation in this second category invokes the numerology of baseball. Every statistics maven knows that following the introduction of the lively ball in the early 1920s (and Babe Ruth's mayhem upon it), batting averages soared in general and remained high for twenty years. League averages for all players (averaged by decade) rose into the .280s in both leagues during the 1920s and remained in the .270s during the 1930s, but never topped . 260 in any other decade of our century. Naturally, if league averages rose so substantially, we should not be surprised that the best hitters also improved their scores.

Still, this simple factor cannot explain the phenomenon entirely. No one hit .400 in either league during 1931-40, even though league averages stood twenty points above their values for the first two decades of our century, when fancy hitting remained in vogue. A comparison of these first two decades with recent times is especially revealing. Consider, for example, the American League during 1911-20 (league average of .259) and 1951-60 (league average of .257). Between 1911 and 1920, averages above .400 were recorded during three years, and the leading average dipped below .380 only twice (Cobb's .368 and .369 in 1914 and 1915). This pattern of high averages was not just Ty Cobb's personal show. In 1912 Cobb hit .410, while the ill-fated Shoeless Joe Jackson recorded .395, Tris Speaker .383, the thirtyseven-year-old Nap Lajoie .368, and Eddie Collins .348. By comparison, during 1951-60, only three league-leading averages exceeded Eddie Collins's fifth-place .348 (Mantle's .353 in 1956, Kuenn's .353 in 1959, and Williams's .388, already discussed, in 1957). And the 1950s was no decade of slouches, what with the likes of Mantle, Williams, Minoso, and Kaline. A general decline in league-leading averages throughout the century cannot be explained by an inflation of general averages during two middle decades. We are left with a puzzle. As with most persistent puzzles, what we probably need is a new kind of explanation, not merely a recycling and refinement of old arguments.

(continued on page 264)

Continued from page 120

I am a paleontologist by trade. We students of life's history spend most of our time worrying about long-term trends. Has life gotten more complex through time? Do more species of animals live now than 200 million years ago? Several years ago, it occurred to me that we suffer from a subtle but powerful bias in our approach to the explanation of trends. Extremes fascinate us (the biggest, the smallest, the oldest), and we tend to concentrate on them alone, divorced from the systems that include them as unusual values. In explaining extremes, we abstract them from larger systems and assume that their trends have self-generated reasons: if the biggest become bigger through time, some powerful advantage must attach to increasing size.

But if we consider extremes as the limiting values of larger systems, a very different kind of explanation often applies. If the amount of variation within a system changes (for whatever reason), then extreme values may increase (if total variation grows) or decrease (if total variation declines) without any special reason rooted in the intrinsic character or meaning of the extreme value itself. In other words, trends in extremes may result from systematic changes in amounts of variation. Reasons for changes in variation are often rather different from proposed (and often spurious) reasons for changes in extremes considered as independent from their systems.

Let me illustrate this unfamiliar concept with an example from my own profession. A characteristic pattern in the history of most marine invertebrates is called "early experimentation and later standardization." When a new body plan first arises, evolution seems to try out all manner of twists, turns, and variations upon it. A few work well, but most don't. Eventually, only a few survive. Echinoderms now come in five basic varieties (two kinds of starfish, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, and crinoids—an unfamiliar group, loosely resembling many-armed starfish on a stalk). But when echinoderms first evolved, they burst forth in an astonishing array of more than twenty basic groups, including some coiled like a spiral and others so bilaterally symmetrical that a few paleontologists have mistaken them for the ancestors of fish. Likewise, mollusks now exist as snails, clams, cephalopods (octopuses and their kin), and two or three other rare and unfamiliar groups. But they sported ten to fifteen other fundamental variations early in their history.

This trend to a shaving and elimination of extremes is pervasive in nature. When systems first arise, they probe all the limits of possibility. Many variations don't work; the best solutions are found, and variation diminishes. As systems regularize, their variation decreases.

From this perspective, it occurred to me that we might be looking at the problem of .400 hitting the wrong way round. League-leading averages are extreme values within systems of variation. Perhaps their decrease through time simply records the standardization that affects so many systems as they stabilize. When baseball was young, styles of play had not become sufficiently regular to foil the antics of the very best. Wee Willie Keeler could "hit 'em where they ain't" (and compile a .432 average in 1897) because fielders didn't yet know where they should be. Slowly, players moved toward optimal methods of positioning, fielding, pitching, and batting—and variation inevitably declined. The best now met an opposition too finely honed to its own perfection to permit the extremes of achievement that characterized a more casual age. We cannot explain the decrease of high averages merely by arguing that managers invented relief pitching, while pitchers invented the slider—conventional explanations based on trends affecting high hitting considered as an independent phenomenon. Rather, the entire game sharpened its standards and narrowed its ranges of tolerance.

Thus I present my hypothesis: the disappearance of the .400 hitter is largely the result of a more general phenomenon—a decrease in the variation of batting averages as the game standardized its methods of play—and not an intrinsically driven trend warranting a special explanation in itself.

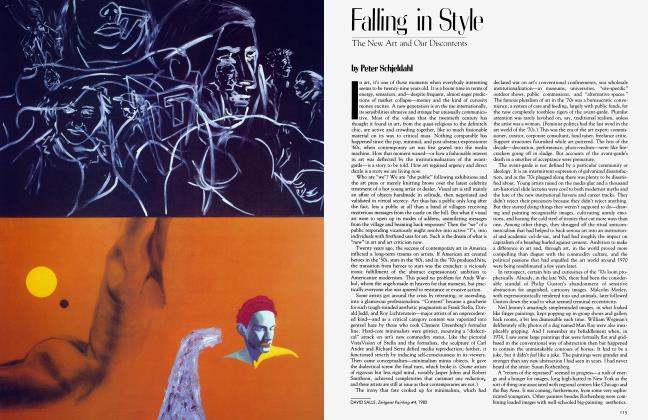

To test such a hypothesis, we need to examine changes through time in the difference between league-leading batting averages and the general average for all batters. This difference must decrease if I am right. But since my hypothesis concerns an entire system of variation, then, somewhat paradoxically, we must also examine differences between lowest batting averages and the general average. Variation must decrease at both ends—that is, within the entire system. Both highest and lowest batting averages must converge toward the general league average.

I therefore reached for my trusty Baseball Encyclopedia, that vade mecum for all serious fans (though, at more than 2,000 pages, you can scarcely tote it with you). The encyclopedia reports league averages for each year and lists the five highest averages for players with enough official times at bat. Since high extremes fascinate us while low values are merely embarrassing, no listing of the lowest averages appears, and you have to make your way laboriously through the entire roster of players. For lowest averages, I found (for each league in each year) the five bottom scores for players with at least 300 at bats. Then, for each year, I compared the league average with the average of the five highest and five lowest scores for regular players. Finally, I averaged these yearly values decade by decade.

In the accompanying chart, I present the results for both leagues combined—a clear confirmation of my hypothesis, since both highest and lowest averages approach the league average through time.

THE DECLINE IN EXTREMESS

Our decrease toward the mean for high averages seems to occur as three plateaus, with only limited variation within each plateau. During the nineteenth century (National League only; the American League was founded in 1901), the mean difference between highest average and league average was 91 points (range of 87 to 95, by decade). From 1901 to 1930, it dipped to 81 (range of only 80 to 83), while for five decades since 1931, it has averaged 69 (with a range of only 67 to 70). These three plateaus correspond to three marked eras of high hitting. The first includes the runaway averages of the 1890s, when Hugh Duffy reached .438 (in 1894) and all five leading players topped .400 in the same year. The second plateau includes all the lower scores of .400 batters in our century, with the exception of Ted Williams (Hornsby was tops at .424 in 1924). The third plateau records the extinction of .400 hitting.

Lowest averages show the same pattern of decreasing difference from the league average, with a precipitous decline by decade from 71 to 54 points during the nineteenth century, and two plateaus thereafter (from the mid-40s early in the century to the mid-30s later on), followed by the one exception to my pattern—a fallback to the 40s during the 1970s.

Nineteenth-century values must be taken with a grain of salt, since rules of play were so different then. During the 1870s, for example, schedules varied from 65 to 85 games per season. With short seasons and fewer at bats, variation must increase, just as, in our own day, averages in June and July span a greater range than finalseason averages, several hundred at bats later. (For these short seasons, I used two at bats per game as my criterion for inclusion in statistics for low averages.) Still, by the 1890s, schedules had lengthened to 130-150 games per season, and comparisons to our own century become more meaningful.

I was rather surprised—and I promise readers that I am not rationalizing after the fact but acting on a prediction I made before I started calculating—that the pattern of decrease did not yield more exceptions during our last two decades, because baseball has experienced a profound destabilization of the sort that calculations should reflect. After half a century of stable play with eight geographically stationary teams per league, the system finally broke in response to easier transportation and greater access to almighty dollars. Franchises began to move, and my beloved Dodgers and Giants abandoned New York in 1958. Then, in the early 1960s, both leagues expanded to ten teams, and in 1969 to twelve teams in two divisions.

These expansions should have caused a reversal in patterns of decrease between extreme batting averages and league averages. Many less than adequate players became regulars and pulled low averages down (Marvelous Marv Throneberry is still reaping the benefits in Lite beer ads). League averages also declined, partly as a result of the same influx, and bottomed out in 1968 at .230 in the American League. (This lamentable trend was reversed by fiat in 1969 when the pitching mound was lowered and the strike zone diminished to give batters a better chance.) This lowering of league averages should also have increased the distance between high hitters and the league average. Thus I was surprised that an increase in the distance between league and lowest averages during the 1970s was the only result I could detect of this major destabilization.

As a nonplaying nonprofessional, I cannot pinpoint the changes that have caused the game to stabilize and the range of batting averages to decrease over time. But I can suggest the sorts of factors that will be important. Traditional explanations that view the decline of high averages as an intrinsic trend must emphasize explicit inventions and innovations that discourage hitting—the introduction of relief pitching and more night games, for example. I do not deny that these factors have important effects, but if the decline has also been caused, as I propose, by a general decrease in variation of batting averages, then we must look to other kinds of influences.

We must concentrate on increasing precision, regularity and standardization of play—and we must search for the ways that managers and players have discovered to remove the edge that the truly excellent once enjoyed. Baseball has become a science (in the vernacular sense of repetitious precision in execution). Outfielders practice for hours to hit the cutoff man. Positioning of fielders changes by the inning and man. Double plays are executed like awesome clockwork. Every pitch and swing is charted, and elaborate books are kept on the habits and personal weaknesses of each hitter. The "play" in play is gone.

When the world's tall ships graced our bicentennial in 1976, many of us lamented their lost beauty and cited Masefield's sorrow that we would never "see such ships as those again." I harbor opposite feelings about the disappearance of .400 hitting. Giants have not ceded to mere mortals. I'll bet anything that Carew could match Keeler. Rather, the boundaries of baseball have been drawn in and its edges smoothed. The game has achieved a grace and precision of execution that has, as one effect, eliminated the extreme achievements of early years. A game unmatched for style and detail has simply become more balanced and beautiful.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now